Archaeologist Pheng Sam Oeun was chatting with a park ranger at Preah Vihear when the artillery barrage started. It was 6:15 p.m. on February 4, 2011, and he had just finished his workday at the administrative center at the base of the mountain where the 1,100-year-old Khmer temple complex stands. In spite of the apparent danger, Pheng and the park ranger stood and watched the scene unfolding in the mountains above: flashes of light from the artillery fire accompanied by the crack of gun shots. “We would see the fire first, and then we heard the sounds,” says Pheng.

Preah Vihear sits just a few hundred feet inside Cambodia’s border with Thailand. Pheng is in charge of preserving the site’s architecture and has been conducting small-scale excavations there, but, predictably, his job is complicated by the conflict.

Half an hour after the fighting had begun, the shelling had grown so intense that Pheng and the park ranger made a run for their bunker, a section of concrete sewage pipe buried under an eight-foot mound of dirt. For three hours they hid there, slapping at malarial mosquitos and waiting for the skirmish to end. At one point, an 81 mm mortar round ricocheted off the stone threshold of an ornately decorated building, chipping it and killing the temple’s photographer. According to news reports, the attack wounded dozens of soldiers and civilians, and at least seven were killed. The incident touched off six months of intermittent fighting at the site.

Cambodia and Thailand have argued and fought over the ownership of Preah Vihear for more than 100 years. But the most recent cause of tension was that the temple complex was designated a United Nations Education Scientific Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site in July 2008. Since then, the site has become the object of political posturing by Thai and Cambodian nationalists alike. At stake is the survival of a unique holy place that is important to the cultural heritage of both nations. Preah Vihear could also be an important source of tourist income for Cambodia’s struggling economy.

Cambodia and Thailand have been colliding in one way or another since the middle of the Cretaceous period, when geologic forces thrust Thailand’s Khorat Plateau above the surrounding plains. The exposed bands of sedimentary rock here and elsewhere became the chief building material for the ancient Khmer Empire, which would ultimately stretch across most of mainland Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Thailand, and parts of Vietnam. For more than six centuries, the Khmer people dominated Southeast Asia, erecting thousands of lavish monuments and developing a complex system of waterways and reservoirs, known as baray, to irrigate their fields and feed their people.

The most famous of the Khmer Empire’s architectural wonders is the former capital of Angkor, known for its elaborate temples, among them Angkor Wat. While Preah Vihear is not nearly as large as the ruins of Angkor, the art and architecture are significant and its setting is far more spectacular.

The first archaeological investigation of Preah Vihear was conducted when the French colonized the region. The first Westerner to see the ruins was French explorer and archaeologist Étienne Aymonier, who came to the temple in 1883 and later described its architecture, as well as the Khmer and Sanskrit inscriptions. Henri Parmentier of the École française d’Extrême-Orient visited the monument in 1924 and returned to clear the vegetation from it five years later, sketching the architecture and describing its iconography. His work clarified the timeline of temple building. But since Parmentier’s time, very little work and no excavations had been undertaken at the site—until relatively recently, when the Cambodian government began preparing to nominate Preah Vihear to the World Heritage List.

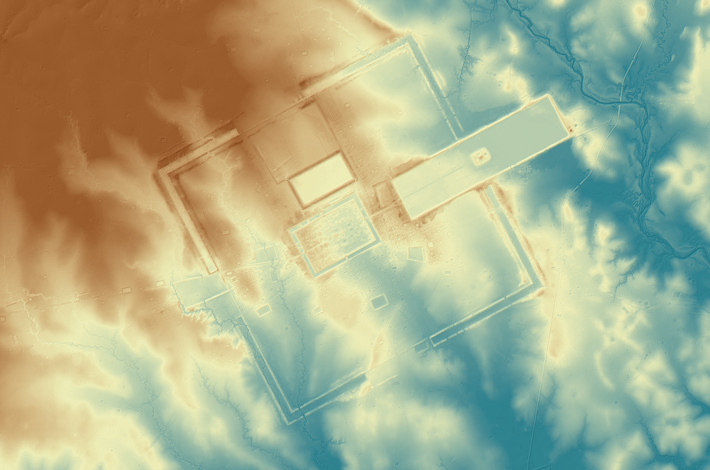

Preah Vihear is a series of buildings arrayed along a 2,600-foot-long central causeway that proceeds dramatically to the edge of a cliff. The complex is meant to represent Mount Meru, the home of Shiva and other Hindu gods. According to Sanskrit inscriptions at Preah Vihear, the temple’s formal origins date to Jayavarman II’s son, Prince Indrayudha, who, in A.D. 893 installed a fragment from a stone monument called a lingam at the site. The lingam, which represents the male sex organ, served two purposes. It was a powerful holy symbol of Shiva, and it was intended to mark Preah Vihear as the northern extent of the Khmer Empire at that time.

Much of the stone construction at Preah Vihear took place in the eleventh century, during the reign of King Suryavarman I, a Buddhist who also worshipped the Hindu gods Shiva and Rama, and was tolerant of a wide range of religious practices. By the twelfth century, Buddhism had become the Khmer state religion and Preah Vihear became a Buddhist sanctuary. A small Buddhist monastery still exists near the ruins and saffron-robed monks come to the 900-year-old buildings to conduct their spiritual practices.

Today, there is a forest at the base of the temple complex near the Thai border. A pair of stone lions flanks the path that leads to a grand staircase and the causeway beyond. The stairs themselves are guarded by sculptures of naga, supernatural multi-headed serpents. Beyond the naga stand the remains of a type of building called a gopura, which were typically built at the gateway of Hindu temples. Little is left standing of the first gopura, labeled gopura V by scholars. There are a few standing columns, some leaning at dangerous angles. The tropical environment has long been exacting a toll on these structures.

The causeway leads past a rectangular pool half-filled with black water and through several more buildings. One of them, gopura IV, is carved with a scene of gods and demons engaged in a struggle to obtain the elixir of immortality. The carving is the earliest known depiction of the Hindu creation story, the Churning of the Sea of Milk.

The causeway ends at an impressive collection of structures. Two buildings flank the entryway to what is called the central sanctuary. Walls surround the sanctuary and the ruins of the main temple buildings stand in the center. Given the way the complex is situated in the landscape, visitors might well expect this last segment of the complex to offer a dramatic vista of the Cambodian plains that stretch for miles beyond. But the temple’s builders had a different experience in mind. The sanctuary’s final wall blocks the scene. Vittorio Roveda, an art historian at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, says, “It was intended that monks not be distracted by the spectacular view.”

The modern-day conflict over Preah Vihear has it roots in the early twentieth century. A treaty between the governments of France and the kingdom of Siam signed in 1904 redrew the border dividing what is now Thailand and Cambodia. French surveyors sketched a line that was supposed to follow the watershed boundary, a line that separates the river basins between the two countries. Near Preah Vihear, the border follows the edge of a cliff but diverges from the cliff near the temple complex so that it is included in Cambodian territory.

In 1953, when France pulled out of Cambodia, Thailand invaded and captured Preah Vihear, prompting Cambodia to file suit in the United Nations’ International Court of Justice in The Hague. During the case, Thailand argued that the French map was erroneous and that the temple actually fell on its side of the watershed. Ultimately, Thailand lost the case because they had not previously disputed the boundaries set and the court took that as tacit acceptance of the borders set by the 1904 map. “One may sympathize with Siam’s lack of topographical expertise at the time,” the judges wrote, “but one is dealing with a sovereign independent State.” The court did not, however, rule on an area of land measuring almost two square miles that surrounds the temple, which has been the site of the recent fighting.

Preah Vihear’s World Heritage List nomination offered a chance for Cambodia to reconcile with Thailand. In 2003, the two nations had agreed to jointly develop the temple and split the proceeds, with Thailand receiving 30 percent and Cambodia receiving 70. The two nations sought to officially list Preah Vihear as a transboundary site that would be cooperatively managed.

Hope for cooperation at Preah Vihear diminished with the rise of the Yellow Shirts in Thailand—a nationalistic faction that ousted the moderate prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra in a 2006 military coup. About two years later, the Yellow Shirts took to the streets to protest the imminent approval of Preah Vihear’s status as a World Heritage site, and called for a criminal investigation of members of the Thai government who supported the listing. Then, on July 15, 2008, a monk and two other Thais entered the disputed territory to plant a Thai flag near the temple. In a separate incident on the same day, a Thai army ranger stepped on an old land mine several miles away and lost a leg. The two incidents led to thousands of troops massing at the border, and the next three years were marked by deadly skirmishes at Preah Vihear and two other disputed sites near the border, Ta Krabey and Ta Moan. In May 2009, Thai heavy weapons fire started a blaze that burned down a Cambodian village near the stairs that lead up to gopura V, displacing 312 families. Both the Cambodians and the Thais have accused each other of laying new land mines at Preah Vihear. The Cluster Munitions Coalition, a civil society campaign that promotes adherence to an international ban on the use of cluster bombs, also concluded that the Thais had fired cluster bombs at the temple and neighboring villages during the clash in February 2011.

More recently, despite this record of conflict, there have been signs that a lasting peace may be possible. In July 2011, the Yellow Shirt government lost power, and the new Red Shirt government seems less interested in fighting over the site. That same month, the United Nation International Court of Justice ordered that both countries withdraw all their troops from the area, and, while there is still some military presence at the site, there has not been any recent shooting. The court has also scheduled hearings for April 2013 to settle the question of which nation owns the disputed territory surrounding the temple complex. The ruling could finally settle the border dispute, allowing the work of preserving and developing the site to begin in earnest.

While Preah Vihear was named a World Heritage site in 2008, archaeologists are still working on a management plan for the site. As part of that plan, Pheng Sam Ouen led a research team that has dug five trenches along a crumbling ancient staircase that leads hundreds of feet up from the valley floor, through a forested ravine, to the base of the temple. Most of the archaeological work at the site is focused on finding ways to preserve the stone buildings, and to allow a 2,500-step wooden staircase to be built alongside the ancient one without damaging any archaeological remains. The excavations have turned up some pottery sherds, roof tiles from the temples, and military artifacts that date to the 1980s, when the Khmer Rouge still controlled the area. Pheng hopes to learn more about the people who lived around the temple. He has found archaeological evidence of seven settlements within the temple complex and five more in the foothills. The remains of a building that may have been a hospital and a small village likely dating to the twelfth century have been found at the base of the mountain. Pheng and his colleagues also hope to restore at least one empty baray at the base of the mountain so that the reservoir can be used for irrigation. They are also building a six-mile-long trench from the baray to carry water to a neighboring village. But there are much bigger hopes that go along with Preah Vihear’s World Heritage site designation.

In 1992, the medieval city of Angkor became Cambodia’s first UNESCO World Heritage site and a major source of income for the impoverished nation. The country had been torn apart by both the Vietnam War and the Khmer Rouge, who ruled from 1975 to 1979, a period when roughly one-quarter of Cambodia’s eight million people died. Helaine Silverman, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has written that by nominating Angkor Wat to the World Heritage List, Cambodia “was demonstrating its definitive victory over the Khmer Rouge,” although the Khmer Rouge continued fighting until the late 1990s. It is hoped that Preah Vihear’s listing will be another step toward prosperity for Cambodia. The site would provide a destination in the less-developed northern part of the country, which might entice some of the tourists who visit Angkor Wat to extend their stays. Nonetheless, that is not likely to happen while the threat of fighting exists. “We are not powerful compared to Thailand,” Pheng says. “There are a lot of Khmer sites in Thailand, and we never think that they belong to Cambodia! I never tell my son that the Khmer Empire once extended to the Chinese border, and when he is older he must take it back.”