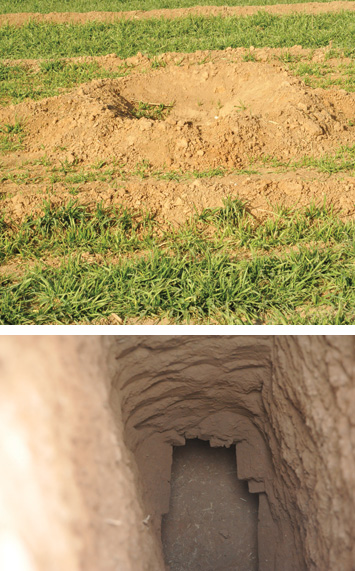

That tree, right there. Do you see that tree?” A portly officer from the Henan Public Security Bureau stood in the cracked mud of an irrigation ditch and pointed at a single, leafless tree in the middle of a field of millet. “If you look to the right, just past the tree, the hole is there.” I looked in the direction he was pointing and told him what I saw: more millet. The officer laughed. “Exactly! That’s how they trick you!”

He was referring to a pile of fresh dirt next to the tree, the only above-ground sign of an 1,800-year-old Wei Dynasty tomb that, only two nights before, had been broken into and looted. It was what I had come to Henan to see, evidence of China’s tomb raiders, criminals who loot ancient graves to feed the antiquities market.

According to some estimates, there are around 100,000 looters in China. Experts guess that more than 400,000 ancient graves have been robbed in the last 20 years alone. Tomb raiders work underground—literally and figuratively—and tend to hang out in the middle of nowhere, in places that were once on the periphery of great cities and rich trade routes. According to the officers who chase them, most are former farmers and peasants. They operate in gangs that teach new recruits how to find and excavate tombs, grabbing only the most desirable artifacts. What they take moves through the hands of middlemen to collectors and auction houses in China and around the world. What they leave behind is a source of endless frustration to archaeologists: damaged, incomplete sites that reveal only a fragmented picture of the past.

Every archaeologist I met in my three years of writing about archaeology in China was familiar with the work of looters. One told me the tomb he was excavating had been raided multiple times—once a few hundred years ago, again in the 1970s, and finally just months before. At an underwater site near Guangzhou, local authorities were constantly chasing off free-diving thieves who tried to sneak by in the middle of the night. Tomb raiders are, by nature, hard to find. In general, archaeologists don’t like to talk about them because the scale of the problem makes it seem as if China is losing control of its history.

On a previous trip to Henan, I was lucky enough to meet an expert in local tombs, Mr. Liu, who grew up in a small village there and has spent his life amassing information about burial practices, artifacts, and the capital cities of various dynasties. When I told Liu, who asked that I not use his real name, that I wanted to get a better understanding of China’s looters, he agreed to help. He had run into, and even interviewed, a few during his career, he said, and would do his best to take me to meet some.

I flew to Zhengzhou, Henan’s largest city, to meet Liu on a snowy Sunday morning. We planned to drive to a small country town where tomb raiders were known to be camping out. Liu pulled up in his car, rolled down the window, and shouted with distress, “I’ve lost my phone!” In China, cell phone contact lists are precious. “There were so many people in that phone,” Liu lamented. Worried that his contacts were lost forever, he drove us out of the city in uncomfortable silence. Liu shook his head and muttered “Shenqi,” or “angry,” under his breath, but didn’t say a word about our destination.

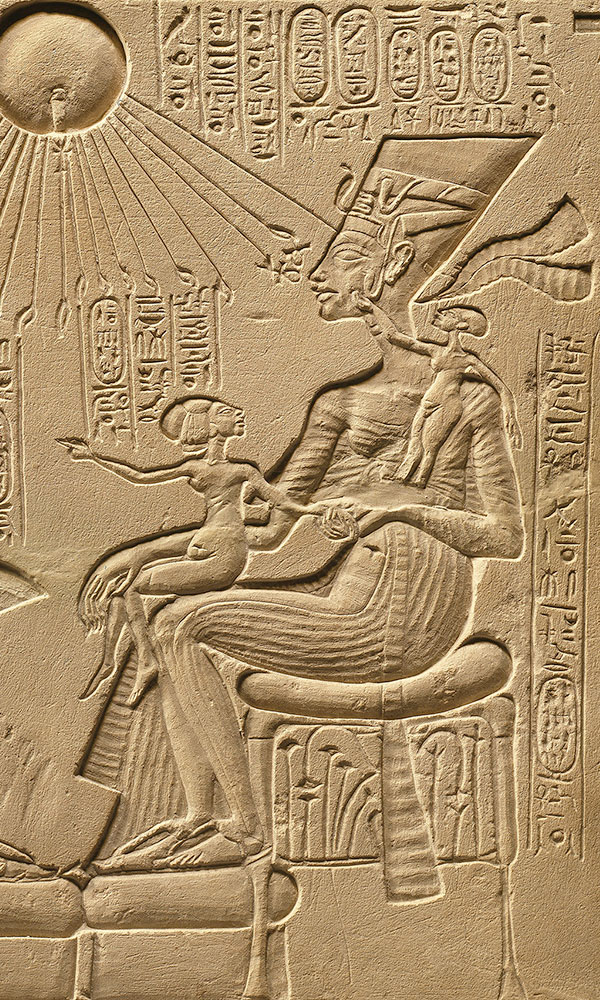

China has a 4,000-year history of building tombs, which were thought to serve as bridges from this world to the next. Building styles have ranged from large pits to pyramids to cross-shaped burial chambers. They were made of brick, packed earth, or stone, and were sometimes capped with ceramic roof tiles. They could vary in size from a few square yards to nearly a square mile. Early on, people filled tombs with bronze vessels and disks and cylinders made of jade, but by the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 25–220), burial practices had expanded to include small replicas of daily life—little buildings, chariots, and ceramic servants. “The objects should resemble those used in real life but be smaller,” an A.D. 1170 book on burial rituals explained. “According to the law, those with rank five or six offices can have thirty objects; those with rank seven or eight offices, twenty objects; and those who have not reached court posts, fifteen objects.”

Tombs were no sooner built than people started thinking about looting them. Researchers in Xi’an believe that even the grave of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, reported to contain a scale model of his entire kingdom (and which abuts the famed terracotta army), was robbed soon after his death in 210 b.c. Chinese archaeologists estimate that, between ancient and modern looters, nine out of 10 tombs have been plundered.

If tombs are bridges between the living and the dead, raiders are intruding on some spiritually fraught territory. According to Chinese mythology, the souls of the dead can linger, particularly if the deceased suffered an injustice. In such cases, the spirits are trapped on earth, in dark, dank places, like tombs, and can enter the bodies of living people. “We grow up with these stories about bad things that happen in tombs,” said Nanpai Sanshu, author of a popular book series, The Tomb Raider Chronicles. “They fascinate us.”

The main character of the series is a reluctant looter, but he has no choice—it runs in the family. “Tomb raiding used to be a family business,” Liu said. “If your father is teaching you how to find a tomb and how best to dig, he is going to teach you the safest way to do it. There were fewer disputes.” Today, Liu continued, the relationships have changed. Tomb raiders are friends or acquaintances, or strangers brought together by larger criminal networks. And according to Liu, this can cause conflicts. He’s seen more than one operation fail when a disgruntled raider ratted out his compatriots. “Maybe someone thinks they aren’t getting paid enough,” Liu said. “Maybe they think things aren’t fair.”

Liu had arranged for us to stop for lunch at an archaeological site on the way to the village. An archaeologist friend of his was working on the remains of a Shang Dynasty port that once sat on the Yellow River. At the excavation, a team of 20 local farmers had cleared a pit about 15 feet deep and 30 feet square. They continued to attack the cold ground with shovels and brushes as we walked through the site. Some of the women stood in the mud wearing heeled dress shoes and others gripped shovels with gloveless hands. Their pay, according to the archaeologist, was low but adequate for rural China. The urge to raid a site is easy to understand, Liu pointed out. A successful tomb raider can make a year’s salary in one night.

“It’s a fact of our work,” said the archaeologist. Tomb raiders ruin excavation sites by taking what they think is valuable and trampling the rest. “Details that a looter doesn’t care about and destroys would otherwise have helped us better understand a site.” Evidence of construction techniques, the placement of objects in a tomb, and their potential significance can be lost. Despite this, Liu and his friend were surprisingly sympathetic to the raiders. “People here grow millet and corn and sometimes green beans,” Liu said. “There’s really no way to make much money.”

Back in the car, Liu announced that he was accustomed to taking a nap at this time of day. He was exhausted after worrying about his phone all night. Near a tollgate, Liu pulled halfway off the road, reclined his seat, and started snoring quietly.

Though it is a centuries-old practice, the methods of tomb raiding have changed dramatically over the past 30 years, as the market for Chinese artifacts has exploded. Raiders have been caught with walkie-talkies, oxygen tanks, lights, and chainsaws. Since the 1990s, China’s security forces have stepped up their efforts, instituting harsh punishments for looting, working with the United States and Europe to stop smuggling, and, last year, creating a national information center.

Some archaeologists say these efforts are having an effect, if a limited one. Tomb raiders today aren’t as brazen as they once were. In a famous case from 1997, reports estimated that more than 1,000 people were looting the ancient tombs built during the Tuyuhun Kingdom (A.D. 417–688) in China’s Qinghai Province. One archaeologist reported that as he excavated one side of a burial site, looters worked on the other. Looters today are just as determined, but perhaps not quite so bold or foolish.

Just before my arrival in Henan, a story had broken about a tomb-raiding ring in Hubei, another province rich in both tombs and looters. Local farmers had reported finding holes surrounded by cigarette butts and litter. Investigators arrived and were able to arrest a group of what some Chinese media outlets characterized as “suspicious people from Shandong.” The arrested looters claimed that the artifacts they took had already been sold to a man called “Little Fatty” for 4 million yuan—around $643,000.

Investigation into the mysterious Little Fatty led to a man named Zhang Moumou. Though Zhang had no apparent profession, he kept two apartments, and large sums of money frequently passed through his accounts. In his two homes, investigators recovered 198 stolen artifacts from all over the country. “The artifacts they recovered come anywhere from the Spring and Autumn Warring States period [771–221 B.C.] to the Jin Dynasty [A.D. 1115–1234],” Bao Dongbo, the director of the Hubei Provincial Archaeological Institute, told me. “When the police found those artifacts, they looked as they would have when first unearthed. The raiders have done no repair or cleaning.” Little Fatty was one of countless middlemen, a stopping point for artifacts passing between the hands of looters and the display cases of wealthy collectors.

“Their method of operation is actually very complicated,” said Bao. “Someone contributes money, someone else contributes labor, someone gives instructions, someone else does the digging. You know, no matter where you are, you can find people who want to make quick money.”

Twenty minutes into Liu’s nap, the sound of running water and chirping birds filled the car. His eyes snapped open. “My phone! My phone is in here somewhere. Help me find it!” Liu frantically jumped out of the car and peered beneath his seat. “My phone! My mood has improved! Now we’re really ready to go!”

Liu was energized. He turned on the radio and drove, humming, to a small town in northern Henan where everyone seemed to know who the tomb raiders were—or at least where they had just been. Someone had raided a tomb two nights prior to our arrival and, fearing an investigation, all the looters had skipped town. “Well,” said Liu, “if we can’t show you tomb raiders, at least we can show you the scene of the crime.”

A local farmer had discovered the hole the previous day and called the security bureau. The two officers who had investigated agreed to accompany us to the site with the head of their office and two other officers. From a ditch, one of the officers, whom I’ll call Yuan, pointed across a field. “Do you see that tree?” he asked. As we walked toward it, Yuan explained that he was part of a patrol that drove around the countryside at night, looking for suspicious people in the fields. “We don’t often catch them this way,” he admitted. “Most of the time, a farmer will call in and we will jump in the van and drive over—that’s how we catch them.”

Next to the tree, we came upon the hole in the ground, about two and a half feet in diameter and surrounded by footprints. We knelt and peered in. About 18 feet down, I could make out the broken roof tiles that marked the top of the Wei Dynasty tomb, and then only darkness. Yuan put his hands out, miming how a tomb raider had gone into a tuck, with his back against one wall of the hole and his feet against the other, and inched down. From there, the raiders had to contort themselves in order to enter the narrow space of the tomb itself. “Once you’re in, you can’t stand up,” Yuan said. “You have to crawl like a cat.” Yuan knew this because he had lowered his partner down with a rope the day before. “We do this with all of the raided tombs we discover,” he said, to look for signs that a tomb is unusual or in danger of repeat looting. Yuan said he has been in more tombs than he can count. This tomb was about 160 square feet and still mostly filled with mud. Most of the tombs in Henan have filled like this over the years, either from cave-ins or from seepage through the tiles or bricks. It was relatively modest inside, Yuan said, with no visible artifacts. The looters had left behind only footprints and pits.

Tomb raiders are difficult to catch, in part because of their efficiency. Teams survey large areas in advance by punching the ground with metal rods. “If there is just earth under you, the rod will go down easily,” Yuan said. “If there is a tomb, you will hit something hard.” Raiders then mark the sites and return later. In teams of eight to 10, they start as soon as it gets dark and work until two or three in the morning. In that time, they must dig a hole to the roof of the tomb wide enough for a man to enter, and then break through. There is more digging inside, along with identifying valuable artifacts and hoisting them back to the surface with ropes. Yuan pointed to footprints leading away from the hole and out of the field. “And then,” he said, “they get out of town.”

Yuan shrugged his shoulders at the prospect of holding back the tide of tomb raiders. “There are too many tombs that have been robbed like this to keep track of,” he said. “We do the best we can.” The likelihood that he would catch those responsible for the hole was slim. He shook my hand and climbed back in the van with the rest of the local security bureau. In a few nights he would be back out again, patrolling.

Liu decided to stay behind in Henan for another day to spend time with friends. On our drive to the train station, he was just as fatalistic as Yuan. “All tomb raiders throughout history have been motivated by money,” he said. “And there have always been tomb raiders.”

Tomb raiding is an unenviable job. Those who do it face asphyxiation from centuries-old air and the grim possibility of being buried alive if there is a collapse. They also brave spiritual risk from ghosts, possession, and even zombies. If tomb raiding is a crime that reaches across Chinese history and superstition, it is also a trade that reaches from the lowest to the highest rungs of the national and global economies. “If there were no market for antiques,” said Liu, “there would be no tomb raiding.”

The past decade has seen a boom in the market. At international auction houses, such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Chinese antiquities regularly blaze past sales expectations to be among the most sought-after relics. In 2011, a sale of Chinese ceramics and artwork at Christie’s in New York took in $38 million.

While international auction houses work under regulations intended to prevent looted antiquities from coming to market, the growth of China’s domestic market has contributed to the demand that has fueled the surge in tomb raiding. In 2012, the country’s art and antiquities market was the largest in the world. In Beijing, I visited an antiques appraiser named Zhang Jinfa, whose office is in a complex called the Ends of the Earth Antiques Town. He was tucked in a sparsely decorated room with a few antique vases in a smudged case and an abundance of cigarette smoke.

“I tell people not to collect antiques,” he said. “It is a big responsibility.” Zhang himself started collecting in the early 1980s because he wanted to connect with China’s history—“feel the weight of it” in his hands. As an appraiser, Zhang has come across many of what he called “recently unearthed” antiquities. These either come from raided tombs or are stolen from construction sites, he explained. In China, virtually nothing that has been newly excavated is legally bought or sold. “You can easily tell what has come out of the ground recently,” he said, from the soil that lingers on objects even after cleaning. The collectors who have brought him these antiquities for appraisal are nearly always aware of what they’ve purchased.

A few days later, I went to Panjiayuan, an antiques market in Beijing that is a well-established part of the tourist circuit. Ninety-five percent of the goods at Panjiayuan, Zhang had warned me, are fakes—reproductions aimed at duping tourists. The ground of the outdoor market is covered in blankets and newspaper where vendors display Mao paraphernalia, fake Tang Dynasty figurines, and the occasional collection of unimpressive but authentic-looking pottery sherds and metal bowls. I stopped to look at a dirty iron pot and asked the vendor where he gets his wares. Every month, he said, he drives five hours to another market in Shandong. I picked up the pot. “Where did this one come from?” I asked. He laughed. “Where do you think?” he said. “From the ground!”