Some 3,000 years ago, throughout Britain, broad changes in settlement patterns, society, and technology were slowly bringing an end to what archaeologists call the British Bronze Age (2500–800 b.c.). In the coming centuries, the Iron Age would emerge. But in the wetlands of East Anglia, referred to as the Fenland, a transformation of another sort, both more conspicuous and tangible, was taking place. Climate change was gradually causing water levels to rise, and, as marshland increased, vital dry land became scarcer. The solution for one small settlement was to build its homes on pylons directly above the water. However, by some twist of fate, shortly after the new settlement was built, it was destroyed by fire—whether deliberate or accidental is not known. The conflagration caused the houses and their contents to collapse into the shallow river below. There, extraordinary circumstances led to their preservation and eventual discovery. Recent excavations of this Late Bronze Age village are providing archaeologists with as yet unmatched insights into the lifestyle and day-to-day lives of Britons three millennia ago. It is considered one of the most important discoveries in the history of British archaeology.

The site, called Must Farm, is named after and located in a modern-day clay quarry outside the town of Peterborough. Until now, much of what is known about Bronze Age Britain has stemmed from investigations of specialized sites such as burial mounds, megalithic monuments, or ritual deposits of bronze weapons. While these types of finds have value, they offer archaeologists little information about ordinary people and everyday life. Even when Bronze Age houses and settlements have been identified, they have yielded scant material evidence.

Thousands of artifacts have been unearthed at Must Farm—from bronze axes to balls of thread. It is, however, not just the sheer volume of ancient material that makes Must Farm unique. It is also how those objects retrieved there relate directly to daily life in the Late Bronze Age, and expressly to one particular, fateful day. “So often in archaeology we see settlements going out of use, we see evidence of destruction,” says Selina Davenport from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) at the University of Cambridge. “But at [Must Farm] we see a moment of use and it’s a moment of life. The fire and the silt together have created an almost complete snapshot of the life of the settlement.”

In prehistoric times, the Must Farm site was part of a low-lying fen connected by the River Nene to the North Sea around 30 miles away. Human activity in the area dates back to the Neolithic period, and settlements there thrived, particularly during the Bronze Age. But waters rising over thousands of years submerged the landscape beneath thick deposits of sediment, clay, and peat, while transforming the entire area into a vast marshland. This process gradually buried archaeological sites deep within the terrain, and the Fenland environment enabled their remarkable preservation.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, engineers started to drain the wetlands to create farmland. In the late nineteenth century, companies began digging into the area around Must Farm for its fine-quality Oxford Clay, on a scale that no archaeological excavation could have matched. In some places, quarrying reached a depth of 100 feet. (Some of Britain’s most important dinosaur fossils were unearthed there by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century antiquarians.) This quarrying process would later create an almost perfect set of conditions for the CAU as they undertook the first extensive archaeological investigation into the deep Fenland. “What made Must Farm different was the nature of the brickworks there,” says the CAU Site Director Mark Knight. “The large-scale extraction of clays meant that we were able to look beneath the thick blanket of peat and for the first time investigate the deeply buried sediments of the Fenland basin—and look what we found!”

The recent story of the ancient settlement at Must Farm began in 1999. An amateur archaeologist walking along a previously abandoned section of the quarry noticed some peculiar wooden logs protruding out of the water in a vacant pit. Having spent some time at excavations in the area, including at the famous nearby Bronze Age site of Flag Fen, he recognized the unusual age of the posts and contacted authorities. Archaeologists confirmed that the wooden timbers dated to between 1000 and 800 b.c. Over the next decade, material recovered during periodic and brief investigations began to intimate that something larger and more significant might be buried beneath the pit. Forterra, the brick-making company that owns Must Farm, planned to reopen that section of the quarry—and, in fact, to build a road over what archaeologists had by then identified as a Late Bronze Age site—creating the first opportunity for researchers to investigate on a larger scale.

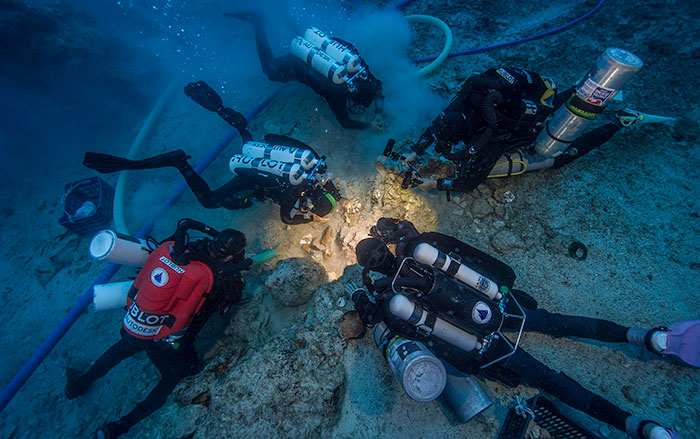

In 2015, the CAU, with funding from Forterra and Historic England, began extensive exploration around the ancient wooden timbers. For 10 months they labored at a stressful and quickened pace in order to excavate, document, and remove the massive amounts of material before the site was due to be handed back to Forterra. It soon became evident that beneath the waterlogged sediments was an entangled mess of wooden beams buried in more than six feet of silt and peat. However, some semblance of organization began to become apparent amid the seemingly chaotic array of blackened timbers, and archaeologists ultimately realized that what they were looking at were the remains of several circular houses. This discovery itself was almost unprecedented within British Bronze Age archaeology. When evidence of Bronze Age houses can be found, it usually only consists of postholes and soil imprints, which is all that remains after the wood, brush, and other materials decay. Must Farm’s anaerobic conditions, however, preserved these building materials.

Initial excavations revealed at least five houses, each of which averaged around 20 to 25 feet in diameter, built close together. A semicircular defensive palisade surrounded the entire complex. Scholars estimate that the small settlement probably consisted of eight to 10 roundhouses within an oval enclosure, but half the site was wiped out by quarry activity in the 1960s. A site of this size may have been home to an extended family unit of perhaps 60 people. Overall, a staggering 5,000 pieces of timber, from thick beams to wood chips, have been recovered. Some of the palisade posts are in such good condition that they look as though they could have been purchased at the modern building supply store down the street. And the cut marks made during the sharpening and shaping of the posts 3,000 years ago are so easily discernable that the CAU researchers are hoping to match individual cuts with specific axes that were also retrieved from the site.

What makes the discovery of these rare houses so astounding is the realization that this settlement had been built directly over an ancient waterway. The houses once stood atop large wooden stilts driven into the river bottom so that each structure hovered about three feet above the water’s surface. Narrow gangways connected individual houses. “It was originally thought that people were only living on the dry land,” says Davenport. “They might occasionally hunt along the fen edge but never live in the middle of the fen. But that’s what we are seeing now—a settlement right in the center of the fen.” Must Farm is the first example of this type of Bronze Age settlement ever found in England.

This way of living may have been the community’s solution to the changing climate conditions that were causing dry and habitable land to become ever scarcer. The remaining pockets of dry land within the fen landscape were essential both for farming and as grazing land for domestic animals, so something had to give. Instead of moving to another location, the settlement simply adapted. “The little islands of dry land are shrinking, and you need those for farming, so you live on the water,” says Davenport. “There is a long history [in the Bronze Age] of building across the fen, so the skills are already there.”

Knight, though, offers an additional theory and suggests that the unusual placement of the settlement at Must Farm was, possibly, a strategic defensive and economic move for the community. “In a world before roads and major forest clearance, the waterways were the thoroughfares connecting people and materials. He says, “The flow of metalwork, for example, would have depended on these channels. By positioning themselves directly on top of the watercourse, the inhabitants of Must Farm were able to exert control over the movement of things, and, at the same time, it gave them a heightened sense of security.” This decision, though, may also have led to the community’s demise.

At some point, when the settlement was still probably less than a year old, it was destroyed by fire. This catastrophe is evident in the blackened beams and ubiquitous charred debris. As the houses fell into the river they settled gradually, thanks to the rather stagnant current, and became embedded in the river bottom. For the first time, archaeologists have learned that the basic framework for each house was provided by three concentric circles of wooden posts, mostly oak, which supported the roof, walls, and floor. These provided the infrastructure to which the woven, wattle-like, paneled walls and floors were secured. The long roof timbers, which formed the conical roof, were covered in a combination of thatch, turf, and clay.

Along with the houses, all of the inhabitants’ household belongings were deposited along the river bottom. As archaeologists gradually began to remove the top layers of burnt house timbers, they were confronted by an extraordinarily rare collection of artifacts preserved within the ruins. These everyday objects, from weapons to tweezers, had been in use right up until the moment the settlement was destroyed, and provide a comprehensive picture of life at Must Farm 3,000 years ago. “When compared to other, later, Bronze Age sites in Europe, Must Farm represents a highly amplified example,” says Knight. “It is our [best] chance to answer questions about lifestyle, appearance, and taste at the end of the Bronze Age.”

The assemblage of artifacts found from house to house was incredibly consistent. They all contained a nearly identical set of objects, permitting archaeologists to create a kind of inventory of a Late Bronze Age household. Each home had a set of various sized pots and storage vessels, wooden furniture, saddle querns, weaving paraphernalia, and metal tools such as axes, hammers, sickles, and spears. Cured legs of meat hung from the rafters. And some activities seem frozen in time. Archaeologists discovered a bowl that still has porridge and a spoon in it, and a garment in the process of being woven.

A great number of high-quality textiles were found, some of which are made from thread as thin as a human hair. They are considered the finest collection of British Bronze Age fabrics ever discovered, and archaeologists remain stunned by their condition. “At the first bit of textile that one of the archaeologists found, she immediately stood up to make sure it hadn’t been torn from her trousers,” jokes Davenport. “It looked that good.”

What makes the discovery of these rare houses so astounding is the realization that this settlement had been built directly over an ancient waterway. The houses once stood atop large wooden stilts driven into the river bottom so that each structure hovered about three feet above the water’s surface. Narrow gangways connected individual houses. “It was originally thought that people were only living on the dry land,” says Davenport. “They might occasionally hunt along the fen edge but never live in the middle of the fen. But that’s what we are seeing now—a settlement right in the center of the fen.” Must Farm is the first example of this type of Bronze Age settlement ever found in England.

Although the Must Farm residents lived on the water, evidence found at the site suggests that they enjoyed a rich and varied diet and retained a vital connection to dry land. Metal farming implements, as well as the preserved remains of porridge made from wheat and barley, confirm that agriculture was a major component of Bronze Age life. However, sheep and cattle bones, along with those of red deer and wild boar, indicate that animal husbandry and hunting also played a major role in the food supply.

Overall, the Must Farm excavations reveal a vibrant, sophisticated Late Bronze Age community. Although its inhabitants may seem to have been living in isolation within a vast wetland, they were highly mobile, both on land and water. They would have been capable of traveling on the river both inland and toward the sea. The evidence of hunting and farming, the presence of timber, and the discovery of a large wooden wagon wheel attest to their ability to navigate their terrestrial surroundings. Artifacts made from jet and amber hint at the settlement’s connections with broader trade networks. At least 18 green and blue glass beads discovered within the ruins originated in Turkey or Syria. (To read about further research on the beads unearthed at Must Farm, go to “Bronze Age Beads Go Abroad,” July August 2024.)

So, how did this seemingly thriving community come to be destroyed? It is apparent that the settlement was consumed by fire, but it is not yet entirely clear how that fired started. Some of the evidence found so far points to arson. Forensic archaeologist Karl Harrison is currently examining the timbers and other available clues. Using modern forensic techniques on a 3,000-year-old, water-saturated site is not without its difficulties. But Harrison is hoping to determine whether the fire began in a single structure and then spread, or whether all of the houses ignited at the same moment. “If each property contains indications of the development of an internal fire, then this begins to look much more like an intentional event,” he says. Thus far, analysis of the charred remains seems to favor the theory that all of the structures were lit simultaneously and, thus, purposely. Additionally, the rather young age of the timbers and the damp conditions of the environment suggest that the roundhouses would not have easily caught fire without some additional assistance. As to motive, Davenport imagines that the location of the Must Farm settlement in the middle of the river may have caused some inconveniences for other local communities. “The river is the only route through the fen, so it is amazing that these people built their houses right in the middle,” she says. “You can’t easily sail your boat down the river with a bunch of houses in the way.” To clear the waterway, perhaps zealous neighbors took matters into their own hands. Still, if the Must Farm settlement were intentionally torched, it does not necessarily signify actions of a nefarious sort—it could have been part of an elaborate religious cleansing ritual.

Although the Late Bronze Age inhabitants of Must Farm appear to have left behind all of their belongings, surprisingly, there is no evidence of the people themselves. No human remains associated with the fire have been found at the site. “It seems the occupants left and did not return,” says Knight. “Maybe they were chased out or compelled to leave? The presence of weapons could suggest a violent end.”

For whatever reasons, the Must Farm community abandoned its Fenland location after the fire. Today the site is notable for its unique characteristics, the quantity and quality of its artifacts, and for the expanded vision of Bronze Age Britain that it allows. The main conundrum facing archaeologists in the future is determining whether Must Farm is actually unique or just the result of a unique set of circumstances. It is the first time that a settlement of its kind has ever been discovered in Britain, but it is also the first time that archaeologists have been able to search so deeply and extensively within a wetland environment. Perhaps communities frequently built their houses above the Fenland waterways, but are buried so far beneath the modern landscape that no evidence of them has yet come to light.

Mark Knight is one who believes that, given the opportunity, and under the right conditions, it may be possible to find sites similar to Must Farm all over eastern England. “We believe the Must Farm pile dwelling is representative of the rest of Fenland. The very fact that the first time we go deep in Fenland we find a site like this establishes emphatically that there are many more ‘Must Farms’ out there waiting to be unearthed,” says Knight. “And that truly creates an extraordinary new image of life in Britain 3,000 years ago.”