Researchers are now one step closer to understanding how apples made the journey from wild populations to grocery stores and farmers markets around the world, and how that process differed from the domestication of grasses such as wheat and rice. The first people to make use of these grasses encountered fields of densely packed wild cereals. The seeds of these self-pollinating annuals drop to the ground when ripe, allowing a fresh crop to grow each year. Over the course of millennia, beginning about 12,000 years ago, humans first harvested, and then domesticated, these crops. Apple trees, on the other hand, reproduce poorly when fallen apples are left to rot, or when second-generation trees grow too close to their parents. They rely on animals—including humans—to disperse their seeds and carry out pollination.

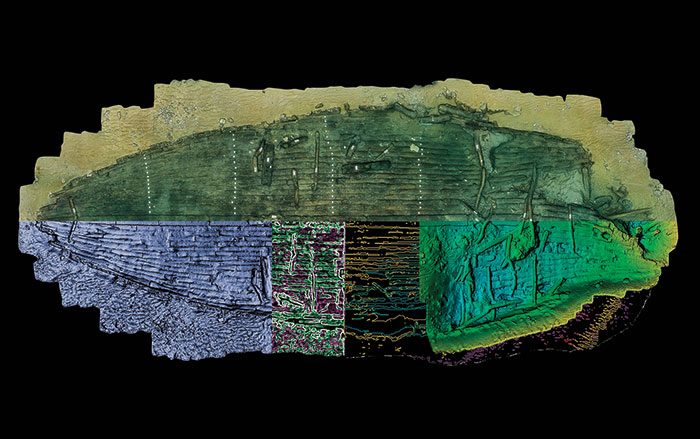

The fossil record suggests that apples developed across Europe and Asia as early as 11.6 million years ago. Apple specimens from a Neolithic site in Switzerland date back to 3160 B.C. Archaeologists have discovered an apple seed from the end of the first millennium B.C. at a village site in the Tian Shan Mountains in Kazakhstan. This is thought to be where the modern apple originated. As part of a quest to determine how apples were domesticated, archaeobotanist Robert Spengler of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History has combined the fossil and archaeological evidence with genetic studies comparing modern apples to their ancient ancestors. He has concluded that the first human populations to encounter wild apples took on a role once performed by now-extinct megafauna, dispersing seeds and pollen, and, inadvertently, expanding the fruit’s range. Says Spengler, “It’s clear that humans are enticed by the same food sources that would have enticed a mastodon.”