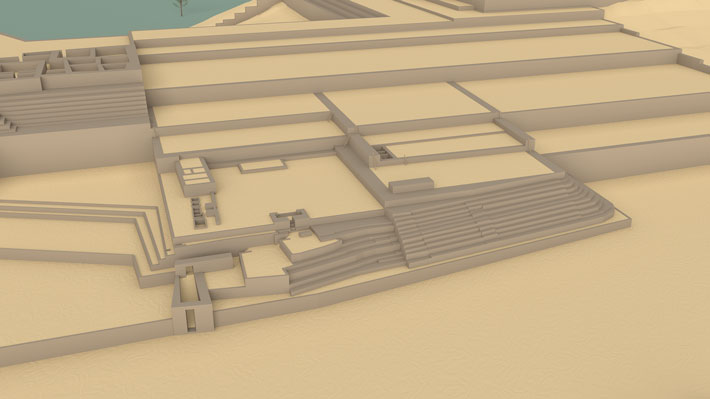

After defeating the forces of Atahualpa, the last Inca emperor, in 1533, Francisco Pizarro dispatched his brother Hernando to a vast religious center on Peru’s central coast called Pachacamac. Just south of modern-day Lima, Pachacamac spanned nearly 1,500 acres and had, by that time, been a place of worship for at least 1,000 years. There, in front of an assembled crowd of locals and priests, Hernando Pizarro is said to have smashed an idol representing one of Pachacamac’s primary deities. The Spanish had introduced a sweeping proscription against indigenous religious practice and forced the local population to convert to Christianity. Pachacamac was soon abandoned, ending a centuries-long tradition of venerating cults at the site under the rule of elites of multiple Andean cultures. These various cultures, evidence suggests, shared spiritual ideas and perhaps even gods. Pachacamac is, in fact, an Inca name for an oracle that may have been worshipped in some form for hundreds of years before the Inca Empire conquered the area in the late fifteenth century.

Just over 400 years after Pizarro’s raid on Pachacamac, in 1938, avocational archaeologist Albert Giesecke discovered a wooden sculpture roughly eight feet tall and five inches in diameter hidden among rubble from what was once the north atrium of Pachacamac’s Painted Temple. The pyramidal Painted Temple is believed to have first been built in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D. and then to have been expanded during the Andean Late Intermediate period (ca. A.D. 1000–1470), when Pachacamac was home to a chieftainship and a deity both known as Ychsma. An American polymath trained in economics who first traveled to Peru in 1909 as an adviser to the Peruvian government, Giesecke became an influential public servant and a champion of the country’s pre-Columbian heritage. With information that had been provided to him by farmers in the area, Giesecke tipped off explorer Hiram Bingham to the location of ruins high above a gorge in the southern highlands—a site now known as Machu Picchu.

Since its discovery, the sculpture from the Painted Temple has been called the Pachacamac Idol and has been the subject of intense interest—and controversy—among scholars of the Andean world. Many have speculated as to whether this idol could be the very artifact Hernando Pizarro is said to have destroyed.

A team led by archaeologist Marcela Sepúlveda of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and the Sorbonne University has now radiocarbon dated the idol. The results suggest it was fashioned sometime between A.D. 760 and 876, around the time the Painted Temple was first constructed. During this period, the central Peruvian coast was under either the direct political control or significant cultural influence of the Wari Empire, whose capital near Ayacucho lay some 200 miles southeast of Pachacamac. According to archaeologist William Isbell of Binghamton University, researchers are divided over how much Wari transformed the region, and Pachacamac in particular. “One scenario would have Wari coming in and, if not founding the major temple at the site, reestablishing it under an imported deity and reorganizing the central coast, probably under theocratic leadership,” he says. “But certainly, the Wari Empire was a pretty aggressive organization and would have been backed up by military power as well.”

Other scholars argue that the transformation that eventually led to the construction of Pachacamac’s temples and its rise as a religious center had taken place centuries before, in the Early Intermediate period (ca. 200 B.C.–A.D. 650), and that the site was already at that point home to a state-level society with a stratified class system, including military and priestly castes, and had a well-developed material culture of its own. This society, in turn, may have adopted cultural practices from, traded with, or become a client state of Wari. While direct evidence of Wari political or military control at Pachacamac is lacking, numerous Wari-influenced burials, ceramics, murals, and textiles have been discovered at the site, particularly in and around the vicinity of the Painted Temple.

Now that it has been dated, the idol may feature prominently in the debate. Its carved decoration has long provided researchers with an opportunity to examine the extent to which it reflects a mix of Wari themes and those already present in the Pachacamac area before Wari’s arrival. At its top, the sculpture bears a carving of two anthropomorphic figures standing back to back, or perhaps one figure with two faces looking out in opposite directions, Janus-like. The middle of the statue is crammed with depictions of animals, particularly felines, fish, and snakes. “The human representations that adorn the idol, as well as the animal and other iconographic motifs that cover its middle portion, refer to symbols that we can call pan-Andean,” Sepúlveda says. “It’s difficult to know if their meanings were the same in various places, or if they varied across time.” Even visually comparable representations, she explains, could have held different meanings depending on context. For instance, similar themes on the idol and on murals identified in the Painted Temple may have had different connotations. “We now know the idol was made several centuries before the last repainting of the temple,” says Sepúlveda. “It is not clear which meanings of these motifs were preserved in time.”

While scholars cannot say for certain what the Pachacamac Idol was called by those who venerated it, it does not appear to depict one of the primary Wari deities. Wari are thought to have worshipped a trio of gods headed by the Staff God, a humanlike figure typically portrayed holding a staff in each hand, with solar rays radiating from around his face. In many instances, he is shown accompanied by two attendants who also hold staffs. Isbell says that if the Pachacamac Idol does represent a Wari deity, it does so in a unique manner. “If it were dead-on Wari style, it would show a recognizable figure from that pantheon—and it doesn’t,” he says. “On the other hand, certain decorative elements it does have, such as pendent rays and feline heads, are very reminiscent of the rays that come off the face of the Staff God.”

Archaeologist Peter Eeckhout of the Université libre de Bruxelles suggests that the idol’s iconography is not purely Wari, but rather a mix of local central coast and Wari styles. “It’s a kind of syncretism,” he says. He explains that the idol shares characteristics with depictions of gods at other coastal sites from the same period, such as a human figure generally shown either as just a head or in full body, often featuring a snakelike headdress or braids. This figure is often surrounded by felines, snakes, and fish, motifs also found on the idol. Colonial accounts written many centuries later suggest that the god of the Painted Temple was variously believed to have been the creator of the world, an oracle, or a deity associated with fertility.

The pervasiveness and continuity of certain religious themes throughout the Andean world may have been a factor in the endurance of the Pachacamac Idol as an object of veneration for at least as long as six centuries (a.d. 876–1533), during which time Pachacamac itself underwent political change and experienced periods of temporary abandonment. Isbell says, “I think the radiocarbon date clearly shows that whether the idol represents the principal image of Pachacamac or not, it was there for a long, long time and participated in a tremendous number of changes that must have occurred on the central coast over those centuries, spanning the Wari Empire, through the Ychsma period, then into the Inca Empire, and through the Inca right to the beginning of the Spanish colonial period.”

Evidence of the spread of religious ideas throughout the Andes can also be found in the use of color across the region, which in turn reflects trade in minerals used for pigment. Such trade networks crossed hundreds, if not thousands, of miles. Using portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, Sepúlveda and her collaborators have revealed that the idol, which now appears unpainted to the naked eye, was once vibrant with yellow, white, and red pigment. X-ray fluorescence detects the concentration of certain elements in or on the surface of an object, in this case the minerals that make up traces of pigment still present on the idol.

Relatively little is known about the ways in which pre-Columbian indigenous people in the Andes thought about color, or how color was employed symbolically. “The main evidence related to the use of color is linked to the work done around metallurgy—its brightness and the intentional search for certain colors through producing particular alloys—or in the creation of dyes for fabric and textiles,” Sepúlveda says. For example, vermilion, a pigment obtained from cinnabar, was used to dye textiles in the Andes for thousands of years, and later for painting murals and wooden objects such as the idol. When the Spanish arrived, Sepúlveda says, they recorded how indigenous people prepared certain colors and dyes. For now, researchers can only hypothesize about what the yellow, white, and red on the Pachacamac Idol might have signified.

The idol may have taken on a meaning recognizable to multiple Andean cultures during the Middle Horizon period (ca. A.D. 650–1000) through its style, color, and decoration, or through a shared understanding of spiritual or religious symbols. It probably endured as an object of worship because new rulers who took control at Pachacamac, such as the Inca, tended to tolerate existing cults. “The Inca were interested in integrating local and regional cults into their own pantheon and sacred net,” says Eeckhout. “It was part of their conquest strategy, but also their belief in the reality of the powers of those entities.” Centuries before, Wari also appear not only to have allowed the people at Pachacamac to continue to worship their local deities, but those gods—including the deity represented on the Pachacamac Idol—may even have been incorporated as lesser members of the Wari pantheon.

Isbell cautions against assuming a straight line of religious continuity at Pachacamac. “There is a tremendous tendency among Andean scholars to imagine some sort of essentialist Andean nature or culture,” he says, “but change has characterized the Andean world throughout its existence.” Spanish proselytizers learned, to their dismay, that even indigenous converts to Christianity viewed that novel dogma through the prism of their own religious traditions, creating a cosmology and a worldview distinct from that of their oppressors. In the decades after the Spanish conquest, mestizo children born to conquistadores and elite Inca women were often trained as priests. When Spanish authorities realized that this new generation of clerics was translating Christian concepts into an Inca language and embedding them within an Inca spiritual framework, however, they forced the mestizo priests out. Perhaps, as they had for hundreds and hundreds of years, the residents of Pachacamac had once again taken in foreign idols and made them their own.