The journey to Kiska Island, at the far western end of Alaska’s Aleutian chain, begins with a 1,200-mile flight from Anchorage to Adak Island. “You show up there and you feel like you’re in one of the most remote places on Earth, and then you get on a ship and sail another day past that to Kiska,” says Andrew Pietruszka, an underwater archaeologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) and lead archaeologist for Project Recover. “The moment you sail in, there are partially submerged ships sticking out of the water and you can see a Japanese midget submarine on shore. It’s like the land of the lost, like you’ve stepped back in time to this amazing natural setting with no modern structures that is so rich in historical artifacts.”

Those artifacts date to a period of unusually high activity on Kiska, during World War II and its immediate aftermath. A narrow, hilly, treeless island measuring less than 30 miles long, Kiska is dominated by a 4,000-foot-tall, snow-covered volcano at its northeastern tip. This landmark, however, is rarely visible, as the island is almost always shrouded in clouds. Located where the warm air of the Pacific Ocean to the south meets the cold air of the Bering Sea to the north, the Aleutians are home to legendarily foul and unpredictable weather: persistent fog in summer, vicious squalls in winter, and relentless chill and winds that blow up to 140 miles per hour year-round. The islands’ native Aleuts, who lived on Kiska at least until the late eighteenth century, when they were removed from the island by the Russians, call the Aleutians the “Birthplace of the Winds.” Kiska’s ground is mostly boggy muskeg, a dense, squishy mat of decaying vegetation that makes it challenging to get around even on the rare clear, calm day. “Imagine you’re walking on a waterbed,” says Dirk H.R. Spennemann, an archaeologist and cultural heritage management specialist at Charles Sturt University. “You don’t have a firm footing until you put all your weight down, and sometimes it will then give way a bit more.”

It’s little wonder that, aside from the occasional fur trapper or seal hunter, the island was barely occupied in the first 75 years after the United States purchased Alaska in 1867. Then, in early June 1942, Japan invaded Kiska, along with Attu, a larger island some 200 miles to the west. The attacks were part of a larger campaign that included bombing a U.S. base at Dutch Harbor in the eastern Aleutians and invading Midway Atoll, more than 1,800 miles to the south. In the six months since the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan had pressed its advantage, taking much of Southeast Asia and the islands of the South Pacific while sinking a large number of Allied ships and losing few of its own. In April, however, U.S. planes had carried out the Doolittle Raid, slipping into Japanese airspace to bomb Tokyo and other targets. Alarmed at their vulnerability, the Japanese were determined to establish a defense perimeter from the Central Pacific to the North Pacific Ocean to detect and counter future attacks. In particular, the western Aleutian Islands, located just 750 miles from Japan’s northernmost base, on Paramushiro in the Kurile Islands, were seen as a potential launching pad for a U.S. invasion.

The Japanese had hoped to deliver a fatal blow to the Allied Pacific Fleet in the Battle of Midway, but instead were routed. They did, however, succeed in occupying Kiska and Attu. The only inhabitants of Kiska at the time were the 10 crew members of a U.S. weather station, who put up little resistance. Despite an extensive U.S. bombing campaign and the notorious weather, the Japanese held both islands well into 1943 before they were retaken by the United States. After maintaining a presence on Kiska to prevent the Japanese from returning, the U.S. military left the island in 1946 and it has been uninhabited ever since. Today, it is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, overseen by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and visits are by permit only.

Kiska is a nearly unique example of a battlefield landscape that is almost entirely the product of wartime activity, and the island has drawn the attention of archaeologists such as Pietruszka and Spennemann. “Every military action which was not built over or destroyed by the American base development is still there: every single bomb crater, every single grenade crater,” says Spennemann, who has surveyed Kiska’s terrestrial battlefield remains for the FWS and the National Park Service. “The Japanese guns are still pointing skyward the same way they did when the Americans were landing. Nothing has changed.”

Spennemann found one anti-aircraft gun that was in the process of being moved but had not yet been emplaced, still resting on its tires, which are still full of air. He found that the World War I–era Japanese coastal defense guns guarding Kiska Harbor are still outfitted with a rubber buffer to cushion the shoulders of those who turned their wheels to aim them. In the American camp area, Spennemann documented wooden boardwalks that had been built to more easily traverse the muskeg. And the Japanese midget submarine that sits on land near Kiska Harbor sports a large hole produced by a demolition charge set by the Japanese before they left the island, an example of their efforts to render their equipment unusable and to limit American understanding of their technology. By documenting these and other finds, as well as combing through military records, archaeologists have accumulated extensive evidence of how much effort and how many resources both sides put into the struggle for control of a seemingly inconsequential island far from the more famous arenas of World War II.

When Japan took Kiska in June 1942, it had a foothold on North American soil for the first time—even if it was an island few Americans had ever heard of. American military commanders insisted that it be reclaimed. “Push the enemy into the sea,” read the order from the War Department in Washington. “Get Kiska back.” This turned out to be easier said than done. It would be more than a year before the Allies retook Kiska, and throughout that time they would struggle to muster the resources necessary to carry out the mission and to overcome the challenges posed by the hostile weather.

The primary tactic the United States employed against Kiska’s occupiers was aerial bombing. At first, each raid required flying 600 miles each way from an airstrip on Umnak. In September 1942, a new airfield on Adak cut the one-way trip to 250 miles, and in February 1943, an airfield on Amchitka reduced it to just 75 miles. Flying conditions were harrowing—when they weren’t outright impossible. Nearly constant turbulence batted planes around like toys. High winds and fog could send a pilot hundreds of miles off course, and a bomber that flew through a cloud front could emerge encased in ice. In the fall of 1942, the United States lost nine planes to combat in the Aleutians—and 63 to weather and mechanical trouble. Those planes that did return from their missions often had bent wings, loosened rivets, and badly shaken cockpit instruments. The ground crews that serviced them had to rely on wrecked planes for replacement parts.

Once bombers got to Kiska, pilots often couldn’t see their targets due to clouds and fog. They took to flying a preset course starting at the volcano, which usually poked above the clouds. They would then count the seconds before dropping their payload, hoping to hit their target. Frequently, they failed. They often flew at high altitude to avoid being shot down by the extensive array of Japanese anti-aircraft guns on the island, and the wind could easily interfere with their timing or blow their bombs off course.

In his surveys, Spennemann observed the evidence of these near misses on the ground. “You see the gun battery and the bomb craters, and you can see that the Americans tried to knock the guns out and that they didn’t,” he says. “They missed them. They were bombing blind.” In all, U.S. planes dropped 7 million pounds of bombs on the island, but succeeded in little more than harassing their enemy. U.S. bombers did have some success in attacking Japanese ships near Kiska, such as Nissan Maru, an oil transport ship that was sunk in June 1942, and Borneo Maru, a cargo vessel that was severely damaged and ran aground in October 1942. The latter wreck remains partially above water in Gertrude Cove on Kiska’s southern coast. Japanese anti-aircraft gunners were hampered by the poor visibility as well. They would either fire when they heard American planes overhead, or aim at gaps in the clouds and fire when planes appeared.

Historians have frequently portrayed Japan’s invasion of the Aleutians as a feint meant to divert American attention from its real target, Midway. However, Spennemann argues that the evidence from Kiska makes clear that the Japanese invested a great deal of resources there and saw occupying the island as an important strategic goal in itself. He points to the solidity of the wooden barracks they built, which they surrounded with high barriers of sod cut from the tundra to protect against the wind and cold. By contrast, when the Americans retook the island, they camped in tents with low sod barriers. The Japanese also constructed miles of tunnels on the island to provide refuge from U.S. bombs and even installed a network of cast-iron fire hydrants in their navy camp. “All of this indicates a lot of effort and that they intended to stay,” Spennemann says. “You don’t put that effort in for two or three months. This is something the historic data set doesn’t tell you, but which the evidence on the ground shows you.”

Moreover, when the Midway invasion failed, says Spennemann, a good deal of Japanese equipment already on its way there was rerouted to Kiska. This included a midget submarine base and a seaplane base, as well as a range of coastal defense and anti-aircraft guns. However, the midget submarines, which measure less than 80 feet long and held a two-man crew, turned out to be of little use in the rough Aleutian waters. Furthermore, as the Americans built bases closer and closer to Kiska, they came to dominate the island’s airspace, giving the Japanese seaplanes little opportunity to fly. The Japanese did try to build an airfield on the island, but their effort to level the spongy muskeg proved futile. Lacking heavy equipment, they were forced to make do with hand shovels and picks. Whenever they made any progress, U.S. planes would drop a few bombs on the runways and reduce them to a muddy morass.

In early 1943, the United States resolved to invade Kiska with an amphibious landing force. But troops, supplies, and particularly ships were so hard to come by, given all the other active fronts in the war, that the plan was shifted to take Attu instead. Attu was thought to be occupied by only 500 Japanese troops versus thousands on Kiska. By the time of the invasion, on May 11, though, it had become clear there were actually around 2,600 Japanese troops on Attu. Anticipating the U.S. attack, they entrenched themselves in the island’s rugged hills and, in a bloody battle that lasted until May 30, fought nearly to the last man.

In addition to its airfields on Adak and Amchitka, the United States now built one on Attu as well. On June 18, just as the Japanese had feared, the Americans used the new airfield to launch a bombing raid on Paramushiro, their first successful attack on Japan proper since the Doolittle Raid. The Japanese troops on Kiska were increasingly isolated. Already dominant in the air, the United States had set up a naval blockade several months earlier that made it extremely difficult for the Japanese to resupply their troops. The Japanese had had some success evading the blockade with their fleet of giant I-class submarines, each of which measured more than 350 feet long, dwarfing the largest U.S. submarines of the time. Having lost Attu, the Japanese decided in early June to use eight of these I-boats to evacuate their troops from Kiska.

Despite using the largest submarines available at the time, the Japanese would still have needed to make several dozen round trips to take all the troops off Kiska. Then, in the space of a few days, the U.S. Navy managed to sink two of these I-boats, killing the hundreds of evacuees on board. And, on June 22, I-7 was intentionally run aground after a two-day engagement with the destroyer USS Monaghan. Its demise marked the end of Japan’s attempts to remove its troops using submarines.

During a 2018 survey of the waters off Kiska carried out by Pietruszka with colleagues from SIO, the University of Delaware, and Project Recover, an organization dedicated to retrieving the remains of missing U.S. service members, one of the team’s objectives was to locate the wreck of I-7. They found it off the southeast corner of Kiska. U.S. military reports note that, after the Allies retook the island, Navy divers spent a month diving on the submarine to retrieve intelligence. As it turned out, the Japanese had likely beaten them to it. “We came across a reference saying that Japanese divers went out to I-7, tried to recover its codebooks, and then put scuttling charges on it and blew it up,” says Pietruszka.

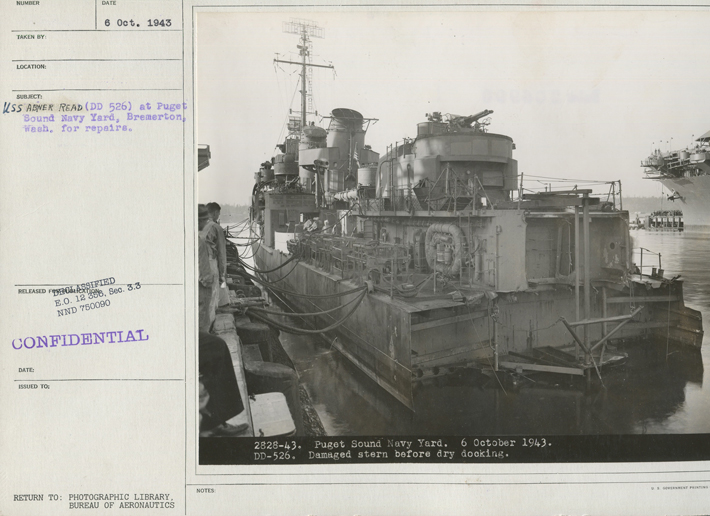

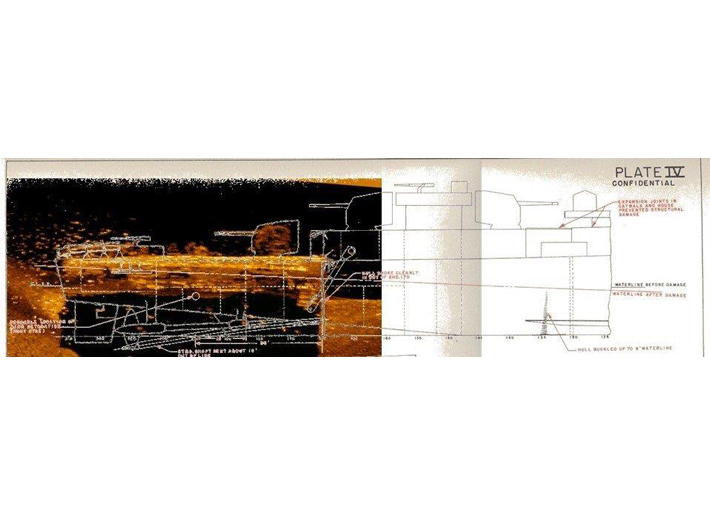

As the Allies geared up for their long-delayed invasion of Kiska in early August 1943, U.S. pilots sent on bombing and reconnaissance missions reported that the island was eerily quiet. Those in command debated whether the Japanese had managed to slip away or had merely retreated to the hills as they had on Attu. They decided to proceed with the invasion in any case, reasoning that it would serve as good training even in the absence of the enemy. On August 15, a joint U.S.-Canadian force of nearly 35,000 troops stormed Kiska, but the Japanese were, indeed, gone. The invasion still took its toll as troops stumbling through the summer fog ended up in friendly firefights with each other, reportedly leading to at least 20 deaths and scores of injuries. Four more men were killed by booby traps set by the Japanese. And, on the night of August 18, USS Abner Read, a destroyer patrolling for submarines off Kiska, struck a Japanese mine, which blew off a 75-foot section of her stern and caused the deaths of at least 70 sailors. Only “extraordinary effort” prevented the entire vessel from sinking and plunging many more into the icy water, according to retired Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, director of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

Guided by a detailed after-action report, Pietruszka’s team had a good sense of where Abner Read’s stern had sunk. However, the site is on Kiska’s western side, where the wind is fiercest and the sea stormiest, so the team kept an eye out for a break in the weather to search for it. Once they had the opportunity, they found the stern with little trouble. “It was truly one of those X-marks-the-spot things,” says Pietruszka. The stern contains the remains of at least some of the sailors who went down with it, says Cox, and the U.S. Navy plans to leave it in situ as a fit resting place for those who perished at sea. “It’s a war grave, a hallowed site,” he says, “and the United States Navy takes a dim view of anyone pilfering or scavenging war graves.”

Just how the Japanese managed to evacuate Kiska without being detected by the Americans can be attributed to equal parts luck, daring, and organizational efficiency. Having failed to remove their troops by submarine, and fearing that a U.S. invasion was imminent, the Japanese boldly opted to send in a surface fleet to do the job. On July 28, 1943, the 5,183 Japanese Army and Navy personnel remaining on the island were all ushered onto eight ships in around an hour. Space was extremely tight, and the troops left behind almost all their weapons and equipment, even dropping their small arms at the water’s edge to lighten their load. Some guns were later found in shallow water by American troops, and Spennemann believes that more must still lie at the bottom of Kiska Harbor. “The Japanese pulling out that number of troops undetected is absolutely unbelievable,” he says, noting that there were no piers on the island at the time, and all these troops had to be ferried out to the ships on small launches. With that, the Japanese had made it off Kiska more than two weeks before the American invasion.

The summer fog had helped the Japanese fleet avoid being seen by American planes. In addition, two U.S. destroyers assigned to patrol Kiska Harbor had been called away several days earlier to pursue a number of Japanese ships 80 miles west of Kiska that had been picked up on radar by a U.S. reconnaissance plane. In the ensuing battle, several battleships and heavy cruisers fired hundreds of shells at what turned out to be nothing at all. The U.S. radar had apparently received soundings from flocks of migratory birds, and the engagement has come to be known as the Battle of the Pips—pip being a term for a radar contact. “It’s a battle the Navy would rather just as soon forget,” says Cox. “It wound up being the butt of many jokes.”

For the Japanese military leadership, the withdrawal from Kiska was seen as a tactical victory, says Spennemann. Given that the troops were cut off from a viable supply chain and unable to launch any offensive operations, keeping them there no longer made sense. For the United States, the decision to retake Kiska was driven at least in part by the political unacceptability of allowing an occupation of North American territory to continue. Once U.S. forces had reestablished control of the island, they finished the airfield begun by the Japanese, but ultimately didn’t use it, or any of the other Aleutian Islands, as a launching pad for an invasion of Japan. “The weather was so bad that both the Japanese and the United States quickly figured out that neither one was going to invade the other using the Aleutians as a springboard,” says Cox. In the struggle for Kiska, the weather was always the common enemy. And, in the end, it seems, the weather emerged as the victor.

Slideshow: The WWII Battle for Alaska

In June 1942, the Japanese invaded Kiska, a nearly uninhabited island in Alaska’s Aleutian chain, some 1,450 miles west of Anchorage. Despite orders from the War Department to “Get Kiska back,” it took the United States fourteen months to reestablish control of the island.