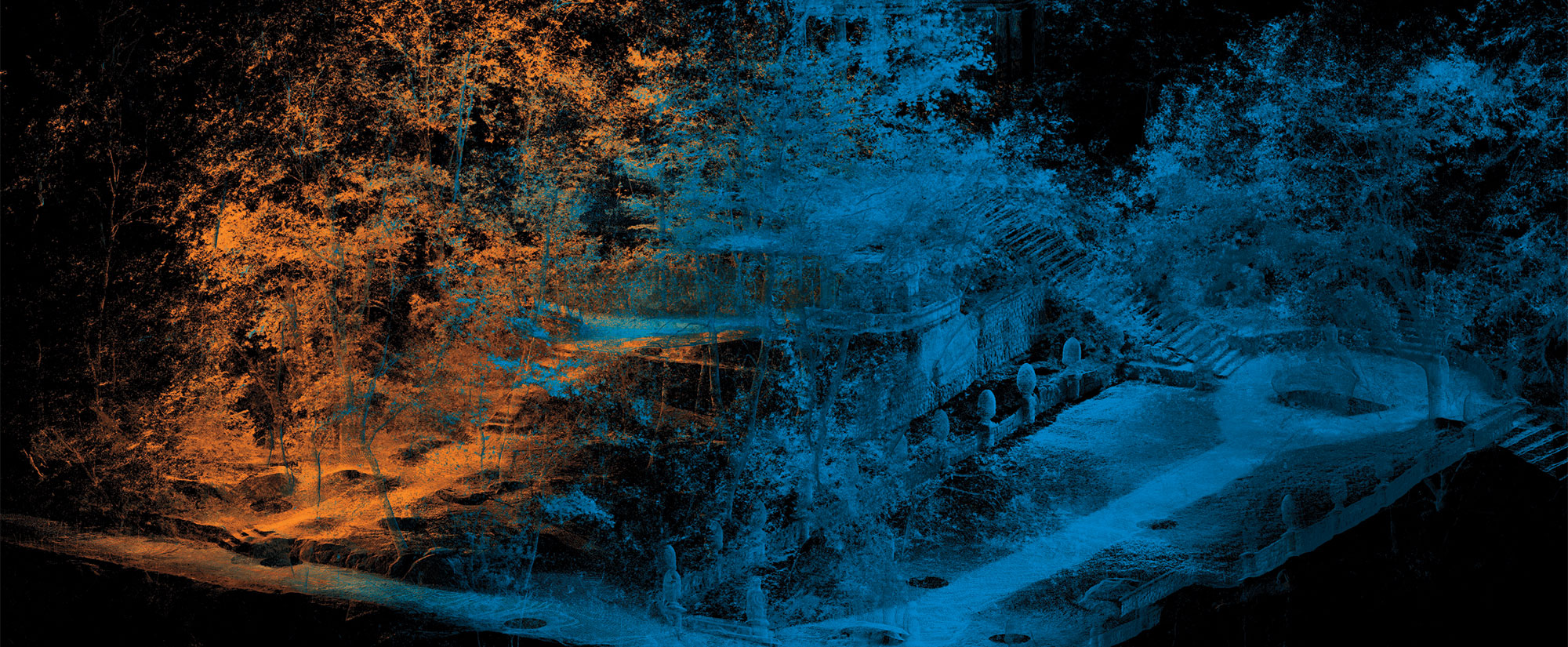

People of the Chancay culture, who lived along Peru’s central coast from around a.d. 900 to 1533, tattooed their skin with intricate geometric designs and images of animals. Some of this artwork is preserved on the skin of mummified Chancay individuals, but the ink has bled and faded as the bodies have decayed over the centuries. This has obscured the designs’ original clarity. A team of researchers led by paleobiologists Michael Pittman of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Thomas G. Kaye of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement has devised a novel way to examine ancient tattoos on mummified human remains and has used it on examples uncovered in 1981 at a necropolis in Peru’s Huaura Valley. The method, called laser-stimulated fluorescence, causes preserved skin to glow bright white and increases the contrast between the skin and the ink. This effectively eliminates the blurring effect of the ink bleed, making the outlines of the tattoos appear much more clearly. The team was able to discern exceptionally fine details that were impossible to see under white light or even using infrared imaging. These details include lines less than one hundredth of an inch wide that Chancay artisans hand poked with needles to create a pattern of repeating triangles. In some cases, the rendering of these designs is even more precise than similar geometric motifs found on Chancay textiles and representations of tattoos on anthropomorphic ceramic figurines.