And so it proved, for within that time the ship and the pyre, the girl, and the corpse had all become ashes and then dust. On the spot where the ship stood after having been hauled ashore, they built something like a round mound. In the middle of it they raised a large post of birch-wood on which they wrote the names of the dead man and of the king of the Rus, and then the crowd dispersed.

The Risala, Ahmad Ibn Fadlan

First-hand accounts of ancient funerary rituals are exceedingly rare, leaving researchers to piece details together from archaeological evidence and ethnographic studies. One exception is found in The Risala, a report written by an emissary from the caliph of Baghdad named Ahmad Ibn Fadlan that includes an eyewitness account of the funeral of a Viking chieftain. In a.d. 921, Ibn Fadlan traveled deep into the Khaganate of the Bulgars on the banks of the Volga River in what is today Russia. His detailed account of the preparations and the ceremony he saw there is both vivid and chilling. Ibn Fadlan describes 10 days of rituals following the chieftain’s death, including animal and human sacrifice, sexual violence, and drunken revelry. These rituals, he writes, culminated in the burning of a ship hauled up from the river along with its honored passenger—the dead chieftain—and an enslaved woman sacrificed during the ceremony.

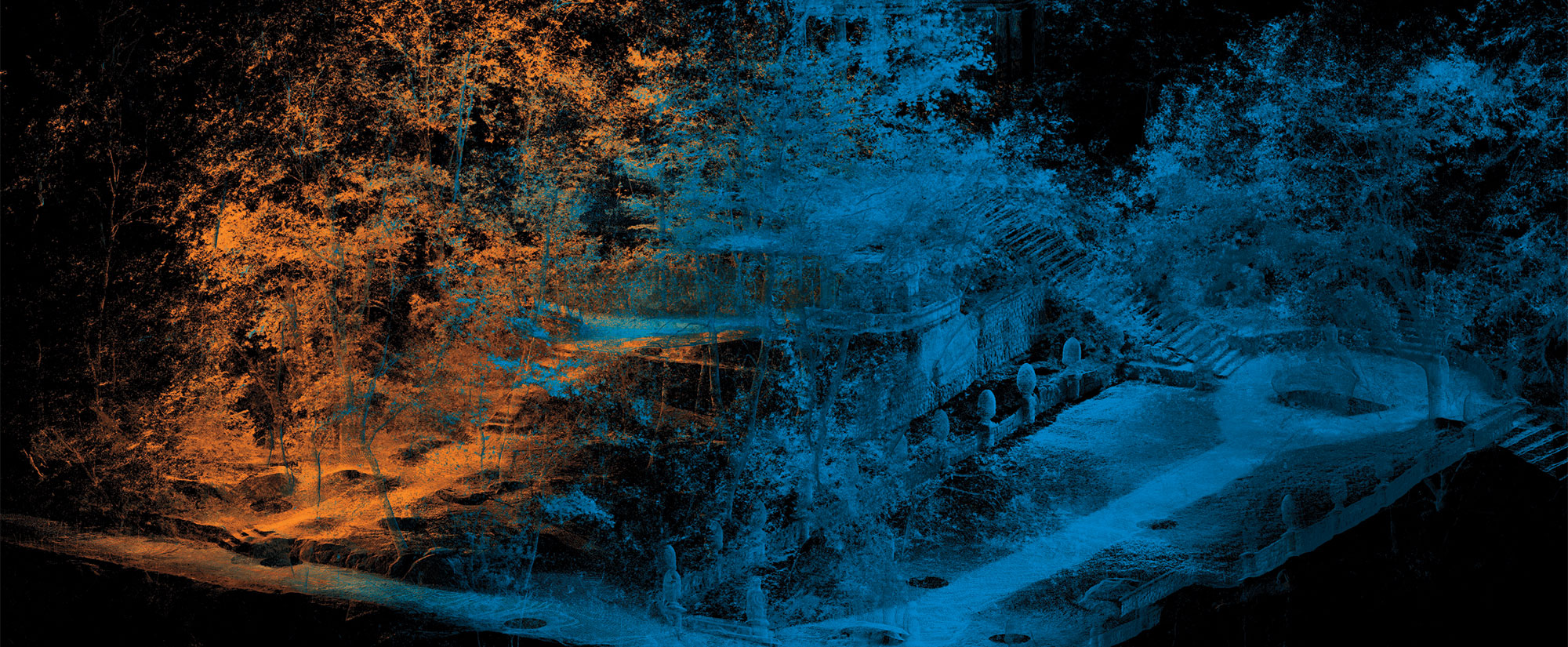

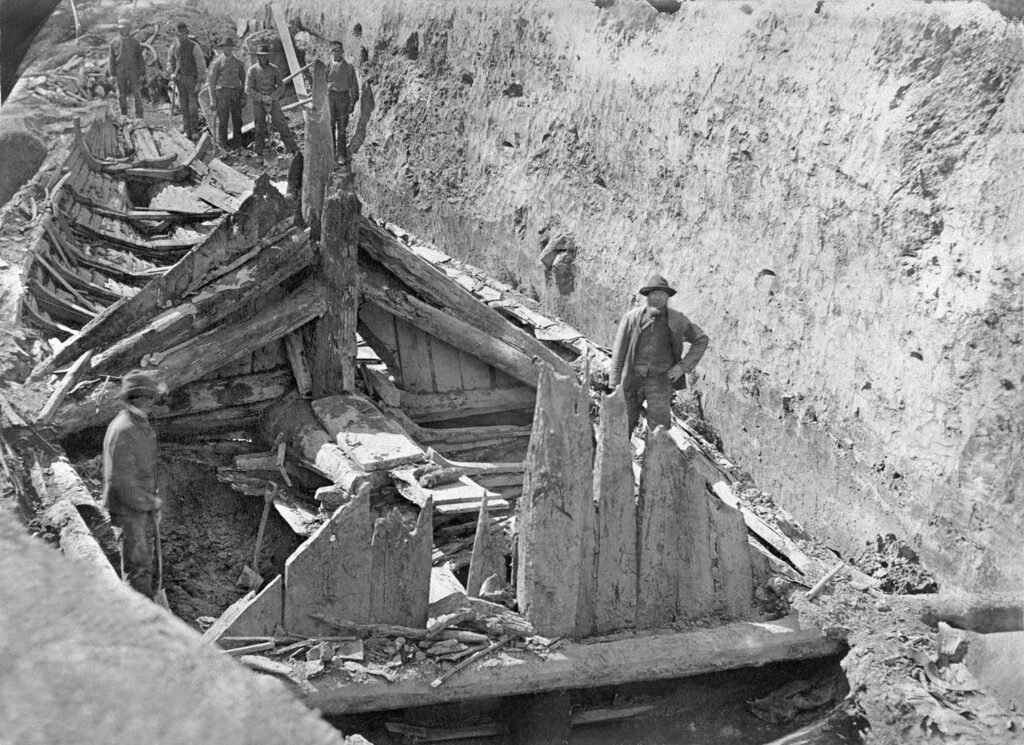

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, multiple such funeral ships were found in Scandinavia, where the Vikings originated. These ships were typically oceangoing vessels that were repurposed for a final voyage. Because the Vikings themselves left few written records, Ibn Fadlan’s report has been the key source for scholars hoping to understand how a typical Viking ship burial would have unfolded. But Ibn Fadlan was an outsider communicating through a translator. The Risala makes clear that the emissary was both confused and appalled by the goings-on. Over the past decade, scholars have begun to question how representative of reality his account actuallyis. A remarkable discovery in 2018 prompted them to deepen their inquiries. Using ground-penetrating radar, a team from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) revealed the outline of a buried Viking ship in the middle of a potato field near the town of Halden in southern Norway. Over the five years that followed, researchers excavated the remnants of a wooden ship more than 75 feet long that had been buried as part of a funeral. Dendrochronology and radiocarbon dating placed the ceremony in a.d. 800. Called the Gjellestad ship after the name of the farm where it was found, the burial was the first Viking ship grave to be excavated in more than a century.

Inspired by the Gjellestad excavations, researchers are now returning to some sites in Sweden and elsewhere across the Viking world and asking new questions about the role of these graves in Viking society. Their combined efforts are providing a new appreciation of the burials’ complexity. “For so long, archaeology has been focused on the people and the objects within the graves,” says archaeologist Rebecca Cannell of NIKU. “We’re asking what happens when you turn your attention in a different direction.”

These finds have led some archaeologists to propose novel interpretations of the burial mounds in which the ships and their contents were interred and of the tremendous resources Viking communities invested in these monuments. “One hundred years ago, people were mostly interested in the ships,” says archaeologist Christian Rødsrud of the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, lead excavator of the Gjellestad ship. “We’re interested in the construction of the mound itself.” These massive mounds, and the large community gatherings that accompanied their creation, point to an overlooked aspect of the ship burials’ social and religious significance. Some scholars now suggest that an account in the Old English Beowulf comes closer to the archaeological evidence in many Viking ship burials and the spectacle that would have surrounded them than does Ibn Fadlan’s description.

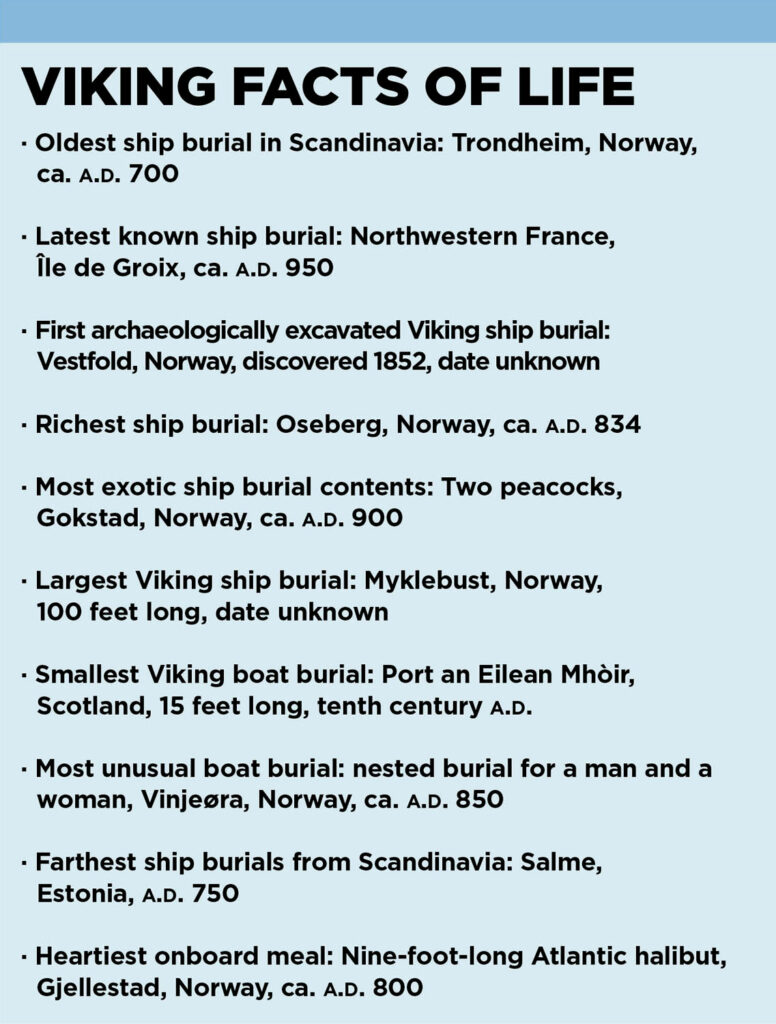

Today, burial mounds can be seen all along the coastal fields and rugged fjords of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, some dating back as far as the Bronze Age, which, in this region, began in about 1800 b.c. and lasted until 500 b.c. “We have hundreds, if not thousands, of mounds,” says archaeologist Morten Ramstad of the University of Bergen. Though many contain small boats, most don’t contain ships, defined as vessels more than 50 feet long. The earliest ship graves in Scandinavia date to the eighth century a.d., coinciding with the beginning of the Viking Age (ca. a.d. 700–1066). This was a time of social ferment caused in part by a warming climate that boosted Scandinavia’s population and spurred technological innovations, allowing people to travel faster and farther than they had before.

Seafaring was the lifeblood of the era. Scandinavians had used oared boats to travel along the coasts of the Baltic and North Seas for millennia, but when they started using sails around a.d. 700—a technology by then long employed in the Mediterranean—it ignited a revolution. Their mastery of sailing enabled Scandinavians to conduct raids as well as trade across oceans, sending Viking warriors as far west as North America and as far east as Constantinople. From a ship’s sails, one of which could require the wool of an entire flock of sheep, to its thousands of iron nails and carefully cut wooden planks, Viking vessels represented an enormous investment.

Not too long after the adoption of the sail, ships began to be included in some of the most impressive Scandinavian graves. Between about a.d. 700 and 950, ship burials appeared everywhere Vikings had a presence, including France, the British Isles, Denmark, and Estonia, though the majority have been found in Norway. Archaeologists believe these burials were once-in-a-generation events reserved only for the most powerful personalities of the Viking Age.

Surprisingly, the first ship grave appears to lie far from Scandinavia, at a site known as Sutton Hoo in the east of England. There, a 90-foot-long ship was buried in about a.d. 610, not long after Anglo-Saxons first arrived from northern Germany and the Netherlands. The ship, which was excavated in 1939, was filled with riches including enameled gold jewelry, silver objects from the eastern Mediterranean, and an extraordinary worked iron-and-bronze helmet. In the middle of the vessel, excavators unearthed a nine-foot-long platform on which the body of an Anglo-Saxon king had been laid before a mound was built over the ship. (See “The Ongoing Saga of Sutton Hoo.”)

For decades after the discoveries at Sutton Hoo, most researchers disputed that there was any connection between the English burial and those in Scandinavia, pointing to the length of time between the Sutton Hoo ship burial and the earliest known ship graves in Norway and Sweden, which scholars then believed dated to the early 800s a.d. In 2023, however, Norwegian archaeologists found the oldest-known ship grave outside England, a burial on the coast north of Trondheim in central Norway that was radiocarbon dated to a.d. 700, forming a sort of bridge between England and Scandinavia. “Now I think that we can say Sutton Hoo really closes the gap in time,” Rødsrud says.

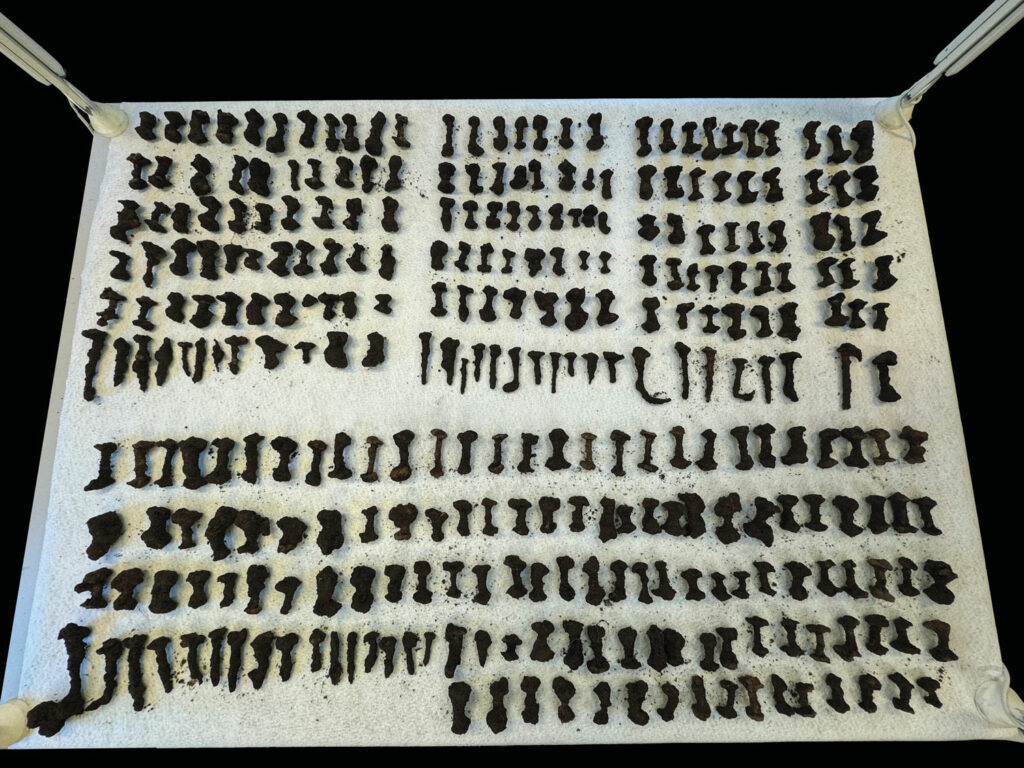

Across thousands of miles and more than three centuries, examples of this type of burial share notable similarities. They contain ships covered by huge mounds of earth. The people on board were typically placed in a chamber at the center of the ship, surrounded by weapons, precious textiles, household items, and sacrificed animals including dogs, horses, and hunting birds. Provisions of food and drink were loaded aboard for feasts in the afterlife. Although the Gjellestad ship was plundered in the distant past, scattered evidence of these banquets survives, including a bone from the tail fin of a nine-foot-long Atlantic halibut.

Ship graves were often located at sites with long traditions of burial mounds, in or among graves dating from hundreds, or even thousands, of years earlier. They have been found atop Neolithic cemeteries and Iron Age sites. Many, including the Gjellestad ship, were next to settlements and cemeteries from the Migration Period (ca. a.d. 400–600). “There must have been a local narrative that these earlier people were the founders of these places,” says archaeologist John Ljungkvist of Uppsala University. “Placing new graves next to old ones is about collective memory.” When Vikings landed on the Isle of Man, they placed a burial in the middle of a Christian cemetery. Cannell doesn’t believe this was intended as a deliberate desecration or to signal dominance. “You could see it in a different way,” she says. “They’re trying to become part of the ritually significant places that already exist.”

For all their similarities, each ship grave also contains unique characteristics. “The burials share many of the same construction principles, and many of the artifacts inside are of the same type, but no two are alike,” says Rødsrud. Sometimes the ships were burned at the culmination of the funeral ceremony, and other times they were buried intact. Most ship burials were outfitted with weapons associated with burials for men, but some of the richest, including the extraordinary ship burial found in Oseberg in southern Norway, were for women. The dead were sometimes laid carefully on beds, while at other sites they were positioned sitting upright in the grave chamber. Still others were burned to ashes. In some burials, artifacts seem to have been carefully placed, while in others they appear to have been hastily thrown aboard, as though in an effort to make a quick escape or as the result of a rushed ritual performance.

In the last 10 years, Cannell has collected hundreds of soil cores from the Gokstad burial in southern Norway and from other mounds to dissect how they were constructed. Her work suggests the mounds were usually prepared in phases: First, turf was stripped away to expose the subsoil; then a depression was dug that would hold the ship upright. Once the ship had been dragged into place from a nearby beach or riverbank, a ring-shaped ditch was often dug around it to separate onlookers from the sacred space within, perhaps for protection against powerful magic that might be unleashed during the ceremonies. In the conclusion of Ibn Fadlan’s account, for example, a man walks backward holding a torch in one hand and covering his backside with the other on his way to light the ship on fire. Scholars suggest this may have been intended to protect his orifices from the burial’s potency.

Next, gray-blue river clay that had been kept pristine was often spread around the ships. At Gokstad, the mound contained an intact ship almost 80 feet long. This was the final resting place of a 50-year-old warrior buried in around a.d. 900. (See “Revisiting the Gokstad.”). Cannell was able to show that blue clay had been piled up around the ship’s hull, creating the appearance of a waterline. “Clay or silt symbolizes the surface of the sea,” Rødsrud says. “They even included the gangplank for going aboard.”

At Norway’s Myklebust ship burial, which was first excavated more than 150 years ago, archaeologists recently revealed an even more dramatic twist on the oceanic scene. Encircling the mound—which, based on the number of boat nails and the outline of the charred vessel, archaeologists believe contained a 100-foot-long ship—excavators found a trench measuring more than 12 feet wide crossed by two bridges, forming what was essentially a moat. The trench was connected to a nearby creek, enabling whoever orchestrated the long-ago burial ceremony to fill it with water. “They burned a ship in a mound surrounded by water,” Ramstad says. “That’s mind-blowing.”

Plant growth in turf blocks stacked for use in the mounds shows that the ships remained completely or partially uncovered for weeks or even months in their pools of clay and water before turf was piled up around them. The ship was then enclosed with dirt and stones, which in many cases later collapsed into the hollow spaces created by the burial chambers or the ship’s decks. “We don’t know how quickly these mounds were built,” says archaeologist Lars Gustavsen of NIKU. “It could have been three weeks, or three months, or thirty years.” The tops of some mounds were altered, or were the scene of later sacrifices that have been found atop them, suggesting they were used for long periods.

From a modern perspective, the huge mounds of earth and stone atop the ship graves, as well as the ships themselves, seem like archetypes of conspicuous consumption. Having the resources to gather enough people to inter a large vessel in a mound, and even to burn it, was a dramatic display of economic and political might. Archaeologists have tended to measure the importance of the person in a ship burial by the vessel’s size and the height of the mound, which they saw as gauges of how much labor a chieftain could command.

Close examination of how the mounds were constructed reveals tremendous forethought and organization. Gustavsen believes that what mattered to the Vikings more than the mounds’ size was how they were created and what they signified. The mound itself, he thinks, was as important as the person inside. Viking sagas do not speak of kings being “buried in a mound.” Rather, the rulers are referred to as “being mounded,” emphasizing the strong connection between the chieftain’s power and the mound. “I don’t think they were thinking about economic cost,” says Gustavsen. “People came together to make the mounds because it was seen as necessary for the community.”

The construction of each mound tells a specific story about the people who erected it and their efforts to memorialize those buried within. “When we look at how the mounds are built, they’re often very intricate,” Cannell says. “It’s not just sort of heaped-up dirt, which is what we would expect if the goal was to build it as fast or as efficiently as possible. A lot of the materials they used, such as river clay and cut blocks of turf, are very difficult to build with.”

The Gjellestad ship mound, researchers believe, once rose 15 feet above the surrounding fields. By the time excavations began in 2019, however, centuries of farming had plowed it flat. Only because a hollow had been dug to accommodate the sleek lines of the 60-foot-long ship did any of the vessel survive. Even then, just the lower part of the hull, equivalent to what would have been below the waterline, was preserved.

Over the course of 1,200 years, the soil atop the ship had been compacted by the weight of the mound above it. Careful excavation methods that weren’t conceivable when the first ship burials were identified have allowed researchers to make out details of the deliberate aesthetic and symbolic choices people made. The timber burial chamber in the center of the ship was surrounded by rectangles of cut turf, compressed over time to layers less than an inch thick. Based on grass preserved in the burial, Rødsrud imagines that a mound built in early autumn might have looked like a golden dome rising above the ship. “It was harvest season, and the grass in the fields was all yellow,” he says. At other mounds, cores show that grassy turf squares were painstakingly arranged in brown-and-green checkerboard patterns of upside-down and right-side-up grass.

The materials used to build the mounds were carefully sourced, seemingly with symbolic intent. Cannell has found that for some mounds, turf was selected from different locations, sometimes miles away, and often from the banks of rivers. The turf, cut from productive farming or grazing land that would have taken decades to regrow in Norway’s harsh climate, would have represented a type of wealth. Earlier graves, perhaps from mounds or cemeteries nearby, were also incorporated, judging by the discovery of human remains that are centuries or more older than the ships themselves. “A lot of Viking mound building, or material, or the way they thought about the world, can seem a bit weird,” Cannell says. “Clearly, the size of the mound wasn’t necessarily the most important factor.”

Viking ship burials, then, were not just the vessels and their contents, but mounds layered with symbolism that could be seen as the Viking equivalent of cathedrals, with all the levels of meaning and community tradition embodied by those buildings. Viewed from this perspective, many of the architectural and design features of the ship mounds begin to seem less obscure. They functioned as grave markers, in part, but archaeologists increasingly believe that they were also stage sets for performances put on for a large audience’s benefit. “It’s a grand spectacle over many days when an important person dies,” Ljungkvist says. “It’s theater. It’s a display, the same as royal funerals today.”

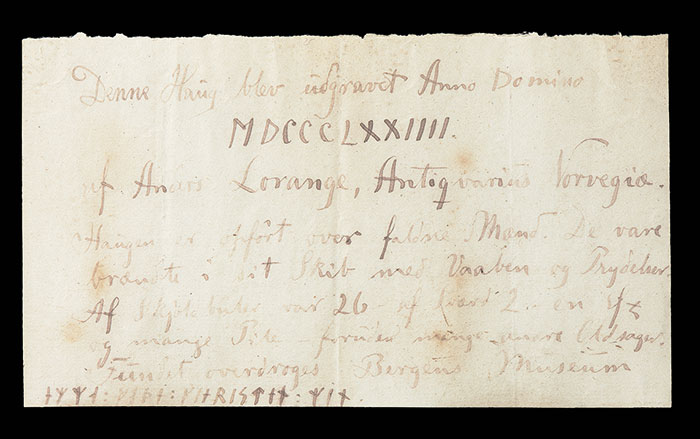

From what Ramstad has reconstructed, the Myklebust ship burial was just such a happening. Inside the vessel, the site’s original excavator, Anders Lorange, discovered a bronze cauldron filled with the cremated remains of a man in his 30s, along with the bones of a lamb or young goat, evidence that at least part of the burial rituals took place in springtime. Among the burned bones was an arrowhead, suggesting a wartime injury. In the cauldron and scattered around the ship were 44 shield bosses—each one perhaps representing a member of the ship’s crew.

At some point, the Myklebust ship was set alight, but that wasn’t the ceremony’s finale. Lorange found that the cauldron hadn’t been warped or damaged by heat. Ramstad believes that the man’s body was burned elsewhere, perhaps after his death on the battlefield or at sea. His remains were then collected and brought to Myklebust, where the cauldron was placed on the burned remains of the ship before a mound was erected over it. “That complexity tells you something about the effort that went into it,” says Ramstad. “This shows that ships were set on fire, as the written sources tell us.”

If the ship burials were grand theater, the ships themselves were the sets. In grave after grave, the vessels seem to have been staged to appear to be on the verge of a voyage. The Oseberg ship was discovered with oars at the ready in their ports, as if the ship were prepared to venture onto the high seas. A large rock had been placed next to the ship’s prow, likely tied to it as a mooring point. “Ships aren’t just objects in the burials,” says Jan Bill, an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. “They depict a departure scene.”

For years, scholars relying on Ibn Fadlan’s account for clues came away with the impression of burials as chaotic, almost senseless scenes of violent excess. However, Bill suggests that when it comes to understanding the mindset behind Viking ship burials, a better source might be Beowulf, the epic poem written down by English monks in the tenth or eleventh century a.d. that recounts events that took place several hundred years earlier. Beowulf, a mythical Scandinavian warrior and king, is the poem’s hero, but its opening stanzas describe the burial of his predecessor, a famed king named Shield Sheaf’s Son, in a “craft fit for a prince.” The anonymous poet recounts that “treasure filled it to the mast, and there was plentiful loot from foreign lands, booty, loaded into it.” Shield’s followers launch the ship to sea once more, “and let him drift to wind and tide, bewailing him and mourning their loss.”

This ceremony had a clear purpose. Shield, the poem claims, “came over the waves as a child,” washing up on a Scandinavian beach in an empty boat as a baby. In other versions of the story, he was accompanied by a bundle of wheat. His burial in a ship signified a return to the sea whence he came. Other epics tell a similar story, identifying Shield as a semi-mythical ancestor of later kings of Denmark and Sweden. Bill says that the spectacular ship burials of the Viking period may have been intended as reenactments of Shield’s story. By re-creating the king’s grand funeral, later Scandinavian rulers borrowed Shield’s legend to connect themselves to a valorous ancestor and legitimize their rule. “These ship burials may actually be representations of that origin myth,” Bill says. “They’re a way of arguing that you can be king.”

They stretched their beloved lord in his boat, laid out by the mast, amidships, the great ring-giver. Far-fetched treasures were piled upon him, and precious gear. I never heard before of a ship so well-furbished with battle tackle, bladed weapons, and coats of mail. The massed treasure was loaded on top of him: It would travel far on out into the ocean’s sway. They decked his body no less bountifully with offerings than those first ones did who cast him away when he was a child and launched him out alone over the waves. And they set a gold standard up high above his head and let him drift to wind and tide, bewailing him and mourning their loss.

Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney