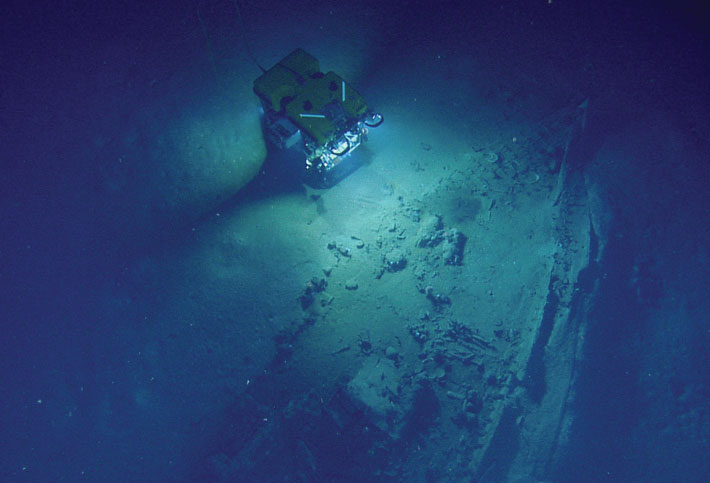

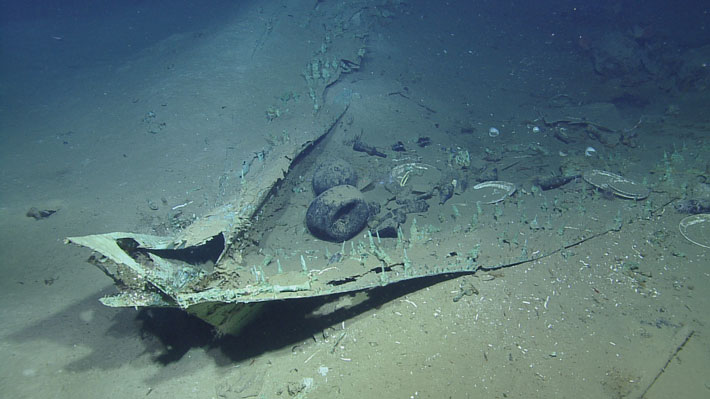

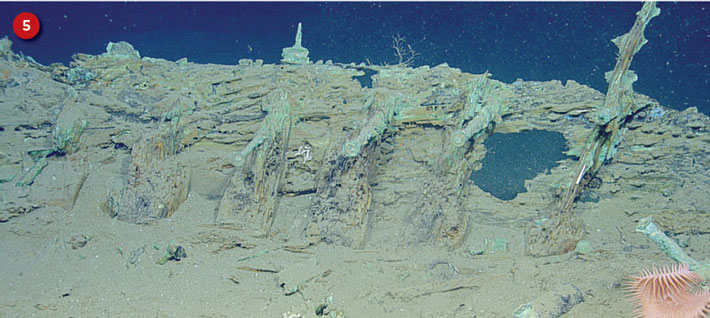

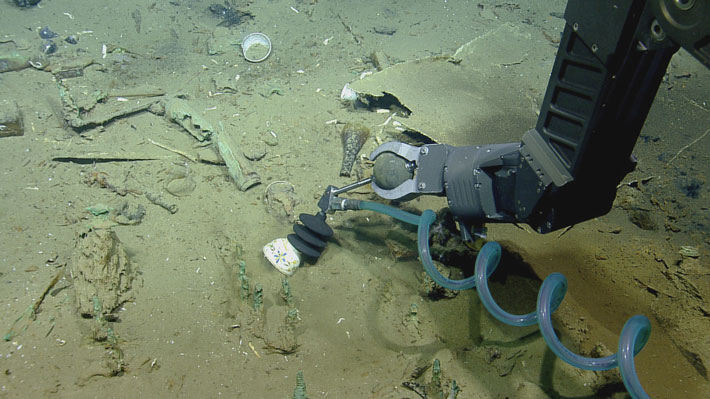

At the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, far enough from both shore and surface that the water no longer carries the silt of the Mississippi, the wreck of a ship rests at a slight angle. The boat’s structure has collapsed and artifacts litter the sandy seafloor—ceramics, demijohns, old medicine bottles, and more. Copper nails and bronze spikes stand in lines where the planks they once held together have partially rotted away. Crouching in the shadow of a toppled, heavily concreted old stove, a long-legged black crab eyes an odd interloper with suspicion. At 4,300 feet below the surface, no human—archaeologist or otherwise—should be bothering it. But, with the help of a remotely operated submersible named Hercules—Herc for short—the crab is enduring a moment of online celebrity. “Folks at shoreside would like to get a measurement on that crab,” a voice crackles over the live video feed. “And let’s take a look at those cannons.”

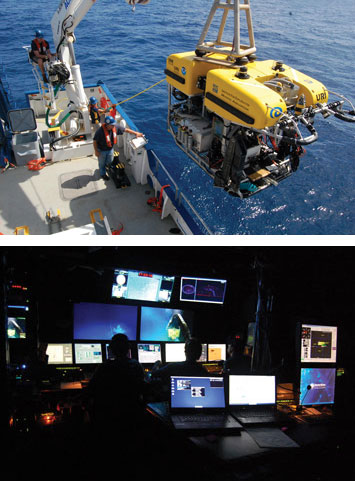

From where Herc hovers, just above the ocean floor, cables stretch up through thousands of feet of murky water to a state-of-the-art research vessel called Nautilus. There, in a room illuminated only by video screens, James Delgado, underwater archaeologist and director of Maritime Heritage at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and Brendan Phillips, one of Herc’s pilots, guide the exploration of the eighteenth- or nineteenth-century wreck they call Monterrey A. From Nautilus, the video feed from Herc is sent by satellite to a building on the campus of the University of Rhode Island. It also goes to various other “command centers,” where groups of scientists gather to communicate directly with an archaeologist on watch duty and to help guide the exploration. The feed is also being streamed live over the Internet, so thousands more people across the world can write in with questions or just have a moment with this big crab and the shipwreck it lives on.

“What’s giving us a sense of the nineteenth century are the anchors, cannons, some of the bottles, and the navigational instruments,” says Delgado on the video feed. “And if the ship had been abandoned, the captain would have grabbed the instruments to navigate the small boat away. This suggests these guys did not make it.”

The study of the Monterrey A has been a landmark project, bringing together archaeologists from around the country in a collaboration facilitated by telepresence—a technology similar to videoconferencing. Except, in this case, the technology is connecting a robot thousands of feet underwater, a ship bobbing 170 miles out to sea, and rooms full of experts on land. The excavation, conducted over seven days in July 2013, was inclusive and public, as anyone with a computer could ride shotgun with Herc and observe the successes and challenges of deepwater archaeology. And, through the wreck, online viewers could explore a time when the Gulf of Mexico was the epicenter of shifting empires—plied with merchant, naval, and privateer ships on missions of commerce, war, and thievery.

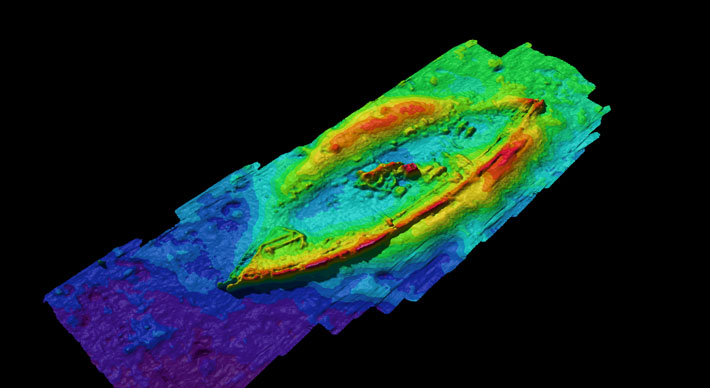

Deepwater archaeology, including the exploration and mapping of Titanic, has benefited greatly from the growing fleet of sophisticated remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) such as Herc (which is among the biggest). It has also benefited, perhaps unexpectedly, from the demand for oil, which has pushed drilling into deeper and deeper water. In the Gulf of Mexico and other U.S. waters, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), which oversees offshore drilling, requires that oil companies look for irregularities on the ocean floor that might be historically important. “The way they find these [wrecks] now is through sonar,” says Jack Irion, an archaeology supervisor at BOEM. “A lot of times these sonar systems are mounted in autonomous, self-propelled submarines. They can be kicked off the back of the ship, and they run and come back.” BOEM keeps a tally of potential shipwrecks—such as the blip caused by Monterrey A—but the sonar maps are frequently inconclusive. “Sometimes the ship is fairly intact and there is enough on it that you can really see that it’s a shipwreck,” says Irion. “Sometimes it just looks like a pile of debris.” Monterrey A, which was discovered by Shell Oil in 2011, was clearly a wreck, but without a closer look there was no telling if it was a historically significant vessel or an abandoned dinghy.

Not all of these sonar hits are examined further, but BOEM’s tally went into the planning for NOAA’s 2012 summer exploration season on the government research vessel Okeanos. The ship was scheduled to be in the Gulf of Mexico and, based on meetings with scientists in the area, NOAA compiled plans for biological, geological, and archaeological studies, including a look at the sonar anomaly at Monterrey A. “We almost didn’t make it to the wreck site,” says Delgado.

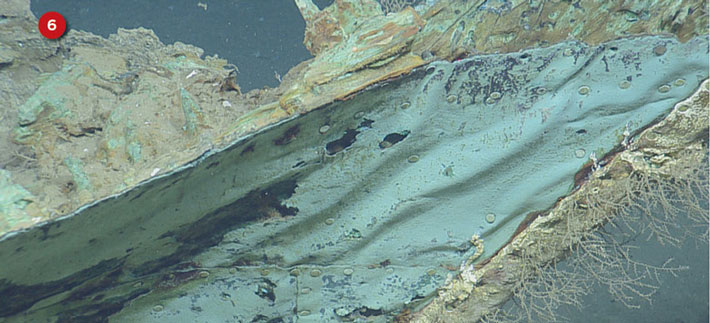

“We got out there and the sea conditions were terrible, so we moved on.” But when the weather cleared up later in the day, the Okeanos crew decided to send their ROV for a short dive. Monterrey A turned out to be an intact wreck, measuring about 84 feet from bow to stern. The ROV’s video feed revealed the hull’s copper sheathing and loads of artifacts: a massive anchor, a variety of bottles (some used to carry alcohol), piles of muskets, six cannons, and ceramic plates and bowls. Navigational instruments, including an octant, fragments of a compass, and sand clocks were visible. And, toward the stern, there were vials and medicine bottles, at least one holding what would prove to be ginger, preserved for hundreds of years. But the crew of Okeanos and its ROV had only the briefest glimpse of the site. Retrieval of artifacts to identify the wreck and detailed mapping would require a larger project and a more sophisticated ROV.

What archaeologists got from the Okeanos visit was just a tease. NOAA and BOEM then spent a year building a team—including the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, which provided both expertise and funding—to rent Nautilus from Robert Ballard, the oceanographer famous for discovering Titanic, and his Rhode Island–based Ocean Exploration Trust. The team would have seven days on Monterrey A, and so would all the viewers at home, since Nautilus’ expeditions are always beamed out live.

Ballard’s mission control, the Inner Space Center (the oceanographer is fond of comparing deep-sea exploration to expeditions to Mars), is on the campus of the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography in Narragansett. The heart of the center is a large room where a gigantic screen looms over several banks of computers and switchboards. For the Monterrey A excavation, a skeleton crew of archaeologists had gathered there, but most times there was little to do but wait. As Herc descended, the archaeologists munched on Red Vines licorice and checked email. But later, when the ROV malfunctioned and pummeled a ceramic bowl into the muck at the bottom of the ocean, they started yelling at the screen like sports fans watching a football game.

Experts on shore were connected to this control room via telepresence, as was a public audience online. According to Ballard, the Monterrey A excavation had as many as 12,000 people logged in at one time. In a side room at the Inner Space Center, a small television studio had been set up, and a team broadcast daily educational programs that allowed audiences online and at museums and aquariums around the world to ask questions of the scientists on the boat. Inclusiveness and publicity were essential to such a large project, but also sometimes presented a difficult balancing act for archaeologists.

“We were a little bit hesitant at first,” says Irion of opening the video feed to the public. For example, if valuable artifacts are found on a wreck site, they might attract looters or salvagers to the area. Or, if an archaeologist makes a premature assessment, a large audience may be there to witness the mistake. One of the artifacts archaeologists were most excited about, for example, was a piece of cloth identified as “the wool jacket.” It tuned out to be a modern T-shirt that snagged on the wreck.

EXPAND

Anatomy of a Deep Wreck

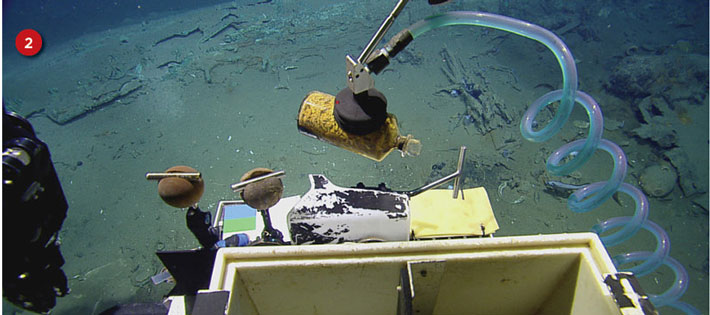

The wreck of Monterrey A was discovered as a blip on a sonar map in 2011, and was first visited by an ROV in 2012. The 2013 expedition produced this photomosaic of the wreck site. Using the sophisticated, but sometimes unwieldy, ROV Hercules, archaeologists and engineers mapped the site in detail and retrieved many items, including a bottle that contains what appears to be preserved ginger, several muskets (which can help with dating and identification of the vessel), and samples of the copper sheathing from its hull.

1) Anchor

2) Medicine bottle

2) Medicine bottle

3) Octant

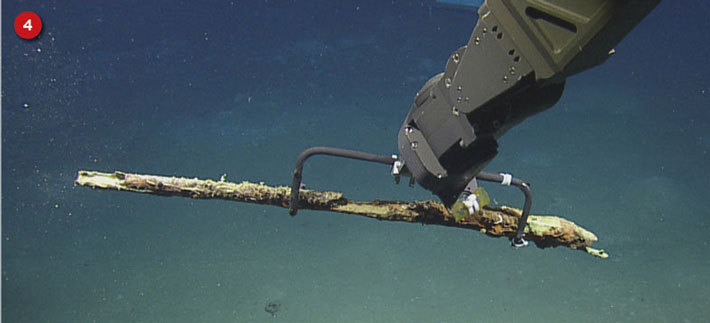

4) Musket

5) Wood and nails

6) Copper sheathing

Archaeology is a challenging pursuit under the best circumstances, and even more so when conducted through thousands of feet of water and via a sophisticated, but sometimes very clumsy, ROV. “This is like parallel parking a truck underwater,” commented one of the engineers controlling Herc. “While you’re not sober,” chimed in another. Something as simple as closing the latch on a box of artifacts could take an hour. “Archaeology is sometimes a destructive process,” Irion adds. Previously untouched sites are dismantled in the course of studying them, as artifacts are removed, moved, and occasionally broken. “Sometimes things happen that you don’t want everybody to see.”

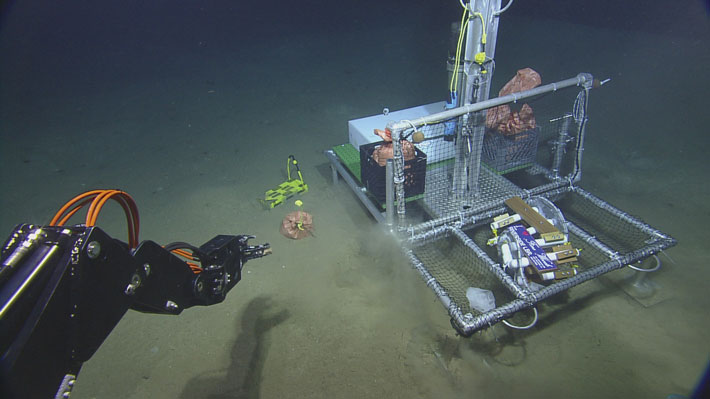

Herc has two hydraulic arms—“Predator” and “Mondo”—held up like a boxer’s. It is also equipped with suction cups, brushes, a little vacuum, and other instruments the arms can grab and manipulate. At one point in the mission, Herc was tasked with loading artifacts onto an “elevator,” a platform designed to drop weights and ascend to the surface in 15 minutes (compared to the hour it takes Herc). The operators spent hours carefully placing and securing artifacts and then, when the moment came to release the latch and let the weights fall away, something got stuck. Using Herc, they tinkered with the weights for over an hour—even lifting and dropping the whole platform several times. Then, with little warning, and with Herc’s Predator arm extended over the platform, the latch released and the elevator shot up, taking the submersible with it. An engineer quickly deployed Herc’s Mondo arm, disengaging Herc from the platform before any damage was done.

Of course, Herc had moments of serendipity as well. Early in the expedition, the first artifact retrieved was a small ceramic bowl. Delgado asked the ROV operator to pick it up with a suction cup. Herc’s Predator arm reached out, moved down slowly, and attached the suction cup delicately to the bowl. “Boom,” the operator said over the video feed. “Magic fingers.”

Despite the hiccups, Irion thinks the openness and transparency of the project made the excavation more interesting. “The more eyes on this, the more details you catch,” he says. Archaeologists got to see what most engages the public, while enthusiasts got to see how archaeologists begin the process of studying an unknown wreck.

The initial dive plan focused on identifying the wreck using artifacts with the strongest diagnostic potential. Buttplates from muskets, for example, often have regiment numbers punched into them that can be traced. Navigational tools can have dates and makers’ marks on them. Ceramics can be dated and traced back to certain sites of manufacture and use. However, many items may be used long after they were manufactured, which can make dating a wreck like assembling a chronological puzzle. The first, brief examination, from Okeanos in 2012, suggested that the ship might date to anywhere from the late 1700s to around 1850.

Wrecks from that time period in this part of the world are difficult to identify. When Nautilus left Galveston for the mission, some archaeologists on board had pinned their hopes on finding a particular ship—a navy vessel that had been custom-made for the Republic of Texas, which existed from 1836 to 1846, after Texas gained its independence from Mexico but before it was annexed by the United States, an event that was a trigger for the Mexican-American War. After a near-mutiny occurred outside New Orleans, the ship disappeared in 1842. Upon closer examination, however, the artifacts, such as ceramics including creamware or pearlware and pieces with different kinds of shell-edges, appear to date to a decade or two earlier.

Excavators saw three spyglasses, including one still wrapped in leather, but none has a firm date attached to it yet. They also identified at least one leather-bound book, but decided to leave this delicate artifact on the ocean floor. “Sometimes discretion is the better part of valor,” says Irion.

Another clue that this was not the Republic of Texas ship was provided by the muskets. “When we saw the video [from the first ROV dive in 2012], we were thinking we were looking at Brown Besses,” says Amy Borgens, state marine archaeologist at the Texas Historical Commission. The Brown Bess muskets, she says, are all over the place. “These are guns that were used for 70 years.” They were first made by the British in 1722, but remained in circulation in the Americas until the mid-1800s. Navies, privateers, or merchants could have been using them. A naval vessel like the Republic of Texas ship would probably have been issued a full set of muskets of the same make—all Brown Besses, for example.

Upon close examination during the Nautilus expedition, however, Borgens found a hodgepodge—some muskets are clearly British, but others could be French, Spanish, or American. While it is unlikely that a naval vessel would have been traveling with such a mixed collection of armaments, that’s not necessarily definitive evidence, according to Borgens, because of the upheaval of that time.

“When you talk about the Gulf in this period, you had all of these European wars coming to an end,” she says, which would have resulted in ships with odd mixtures of weapons and features. New navies were cobbled together with whatever guns or boats were available. The Texas navy started out as a band of privateer boats. Mexico used Spanish boats. And, with the end of the Napoleonic wars in Europe, a British or French captain could well have been piloting a Mexican navy boat. “I’ve seen accounts of U.S. vessel owners taking their boats to Mexico and volunteering them for the Mexican navy,” says Borgens. “What would these vessels look like once you put arms on them?”

Then, of course, there were the privateer ships, which littered the Gulf. Galveston was home to two different bands of pirates, including the crew of the notorious and ruthless French pirate Jean Lafitte. The other band, led by a pirate named Louis-Michel Aury, had such bad luck that Borgen refers to Aury as the “Monty Python of pirates.” Privateer ships, however, are rarely accounted for in official records, so their arrivals, departures, and sinkings may not have been noted. Toward the end of the Nautilus expedition, the privateer theory gained ground when Herc discovered two other wrecks a few miles from the Monterrey A. Though there is no account of three ships disappearing at once that the archaeologists are aware of, it’s likely the three ships went down violently and at the same time—perhaps from a storm. “It’s either that or we’ve found the Gulf equivalent of the Bermuda Triangle,” Irion says.

The artifacts retrieved by the expedition—more muskets, ceramics, navigational instruments, even the sole of a shoe—are still being studied, so they may yet yield some detail crucial to the understanding of the Monterrey A wreck. Learning more might also depend on new expeditions to the other two wrecks. There are no firm plans for this yet, but when the archaeologists return to this part of the Gulf, they might once again have an audience following their every move.

EXPAND

Update From 716 Fathoms

There have been some exciting developments on the Monterrey Wrecks since ARCHAEOLOGY first reported on them in the March/April 2014 issue.

Analysis of the massive amount of data continues. One of the benefits of the technology we used was the constant mapping and remapping of Monterrey A throughout the expedition—at every stage of work, and as artifacts were recovered, a series of measurable maps of the site are now being produced. This has made it possible to follow, virtually, the test excavation and sampling of the wreck over the week-long mission. In addition, the three-dimensional BlueView sonar also provides us with the ability to “fly-through” and measure the site from more than a flat perspective.

For those worried about the fate of the ceramic bowl that Herc’s manipulator appeared to pummel, they’ll be pleased to know it survived, unbroken. After performing well, Herc suffered a hiccup when the ambient sea pressure (1925 psi) formed a bubble in one of the oil-filled hydraulic lines running the arm. Fortunately, each punch hit soft mud and missed the bowl and other artifacts. When the problem was discovered, the team elected to recover the vehicle to the surface rather than risk damaging fragile artifacts where OET's crack team of engineers rapidly diagnosed the problem, repaired it, and got the vehicle quickly back to work. From then on it performed flawlessly for the rest of the mission. This is a complex piece of equipment working in an alien and hostile world and you have to expect the unanticipated mechanical flaw to present itself on occasion, which is when the steely-eyed ROV team leapt into action to save the day.

It is clear to the team that we are looking at a privateer, or a pirate vessel—occasionally one country’s pirate is another country’s privateer. We believe that it was lost with its two consorts, which were likely prizes. This would be the first major find, an underwater archaeological signature of this type of maritime activity resting on the seabed. We’re so excited that, thanks to NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration staging a detailed scientific exploration cruise in the area this spring, we will return soon for a brief inspection with Okeanos Explorer on April 15-16, 2014. You can follow the dives here. We also are planning for more archaeological documentation and sampling in 2015.

Meanwhile, artifact analysis and conservation continues. The modern T-shirt is the first item to emerge from conservation—that was a simple softy-cycle wash—and it turns out to be a coarse fabric tee with the logo of a Manila, Philippines, construction company. The only modern artifact seen on the wreck thus far, the shirt was crumpled in a ball and snagged on copper fasteners beneath the stern. It sure did look like a jacket in all the video and stills, but, as we’re all fond of saying on the team, you never know for sure until you go or recover. While the t-shirt was not, in fact, a jacket from the wreck, it remains an important find. The item highlights the fact that the oceans are a convenient dumping ground for all sorts of modern discards. And there is not a site I’ve visited yet that doesn’t have intrusive materials from our times intermixed with older remains. We found plastic cups, beer cans, and other waste all over the wreck of Titanic, for example.

The archaeological team has also received the initial characterization of the wreck from the oceanography and marine biology team. One of the key questions for us has not only been the assemblage and the hull, but the environmental factors that affect the wreck, as well as the wreck’s effect on the environment. The ship created an oasis of life in an otherwise deep-sea environment, but it also introduced toxins in the form of copper that are now spreading from the corroding metal hull sheathing and spreading into the sediment meters away from the wreck. But in exciting news, two new hitherto undocumented life forms were discovered, another reminder highlighting the fact that the deep ocean truly is earth’s final frontier, capable of yielding information about new life as well as past civilizations as we boldly go.