The lavish water gardens built by the Mughal emperors, who held sway over much of South Asia from the sixteenth to nineteenth century, are some of the most fanciful and aesthetically pleasing waterworks of that era that visitors can still enjoy today. The seventeenth-century gardens at Agra that surround the Taj Mahal, for example, are the handiwork of Persian and Indian workers who endeavored to satisfy the luxurious tastes of their Mughal overlords. Founded by a Muslim royal clan from Central Asia that traced its lineage to Genghis Khan, the Mughals brought Persian-influenced Islamic aesthetics and gardening techniques to northern India, which already had a millennia-old tradition of building monumental wells. James Wescoat Jr., a landscape geographer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says that, initially, the Mughal rulers constructed gardens that were fed by narrow channels, a conservative approach to water use influenced by their origins in the deserts of Central Asia.

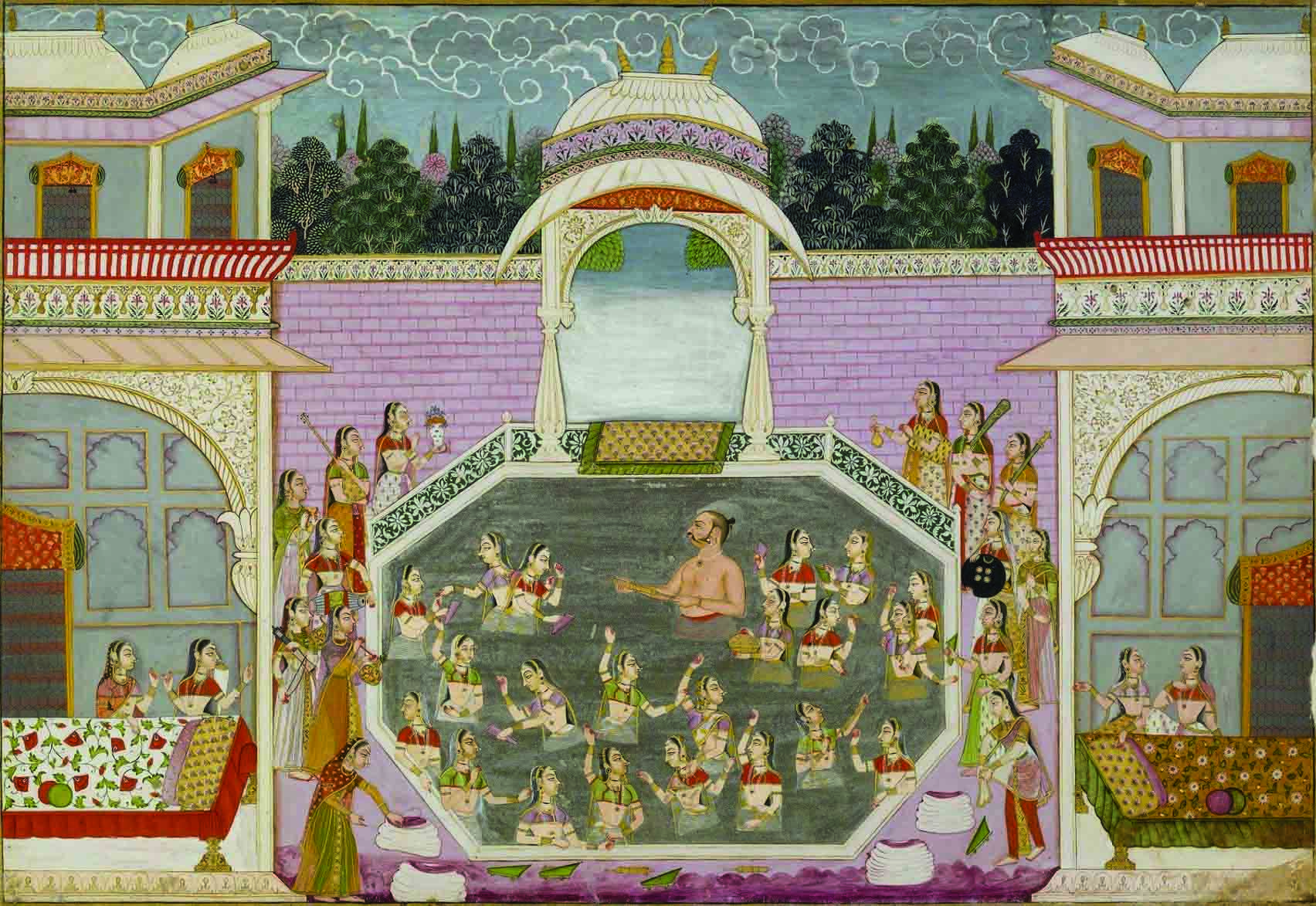

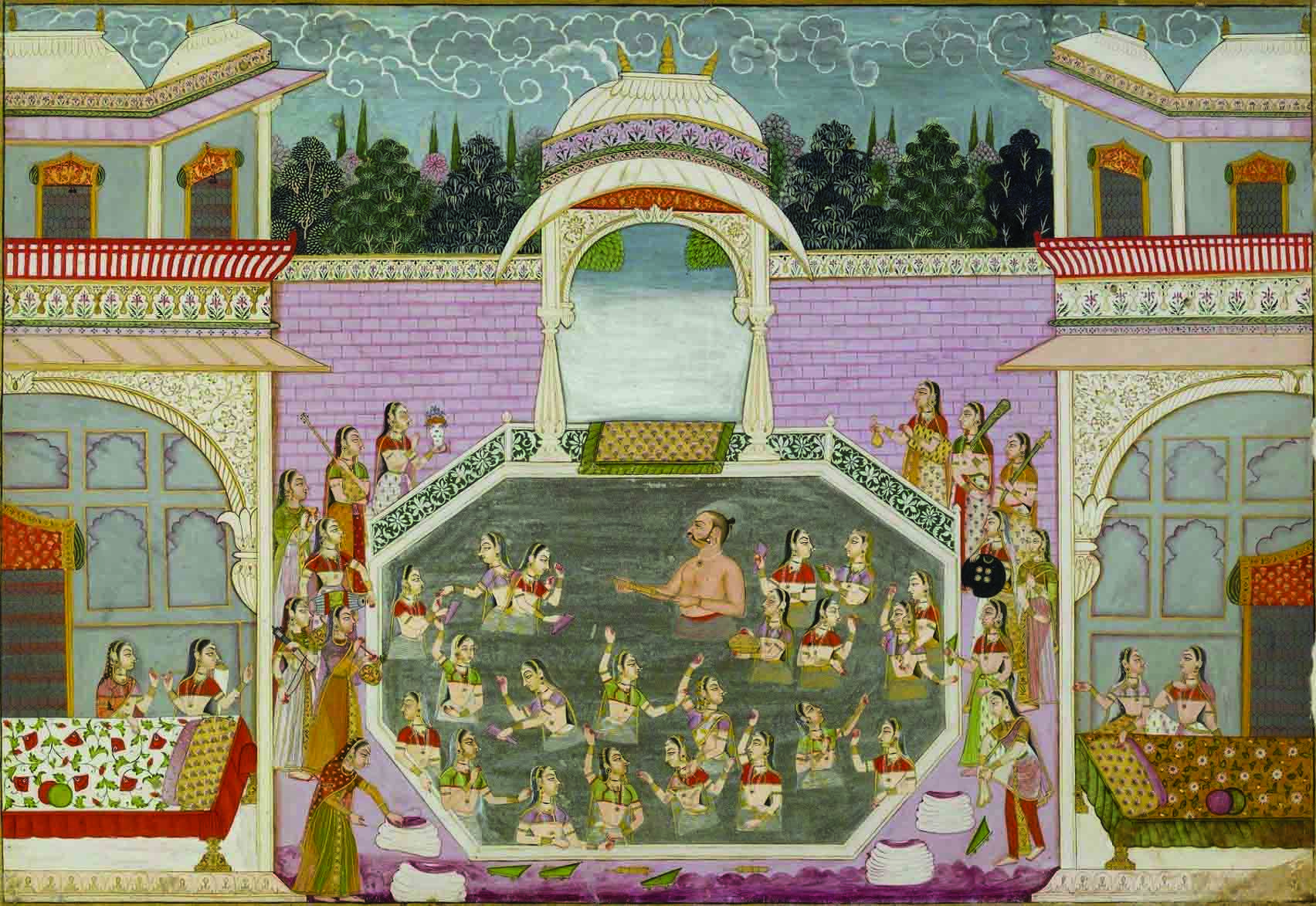

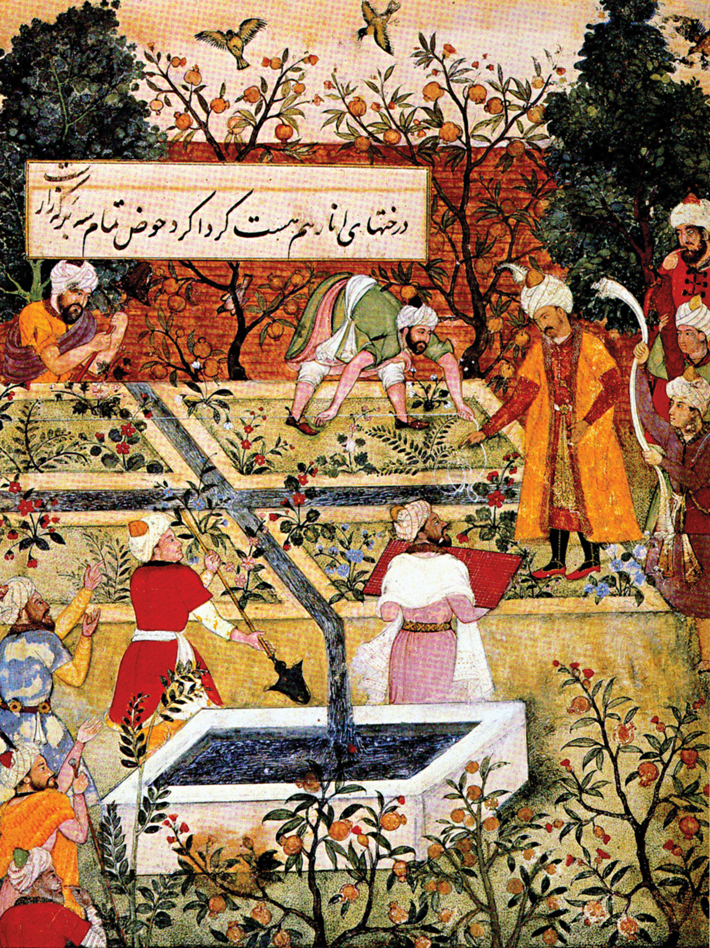

Mughal miniatures and paintings in books offer a window into how water gardens changed over time. One shows the first Mughal emperor, Babur (reigned 1526–1530), overseeing the creation of a garden in Kabul in modern Afghanistan that is fed by precisely laid narrow streams. Known as a charbagh, this type of garden is divided into four quadrants representing the four gardens of paradise described in the Koran. A later painting shows the Maharaja Bakhat Singh, a member of the princely Hindu clans known as Rajputs who often intermarried with the Mughals, celebrating with his harem during the festival of Holi in a large octagonal garden pool at the Mughal-Rajput citadel of Nagaur. “These later gardens are much more elaborate water displays,” says Wescoat. “It speaks to the later Mughal elite becoming more familiar with the Indian landscape.”

Wescoat notes that archaeology and paintings alike may obscure what might have been an important characteristic of such gardens. “The courtly entourages were very mobile,” he says. “Male members of the court were often traveling or prosecuting wars, but the women were more likely to stay in place. It’s interesting to think that the gardens might have been principally enjoyed by women, whose experience in these spaces was less likely to be painted or recorded.”