Storing water was essential to the livelihood of the Swahili people, who flourished along the coast of East Africa from the seventh to sixteenth century A.D. Many still live there today. In the past, they engaged in lucrative trade as far away as China. In the towns they called home, however, the Swahili grappled with an arid climate and water scarcity, enduring a nine-month-long dry season with little to no rain. “All these towns are in slightly different environments, but they’re all in places where access to fresh water is marginal,” says archaeologist Stephanie Wynne-Jones of the University of York. In addition to being used for drinking, cooking, and washing, fresh water was necessary for ritual ablutions required before entering the towns’ mosques and for making the lime plaster the Swahili used to construct their coral houses. At Kilwa Kisiwani and Songo Mnara, two settlements on neighboring islands in the Kilwa Archipelago off the coast of southern Tanzania that Wynne-Jones has excavated, the Swahili devised different ways of collecting and storing fresh water.

During an age of prosperity that began in the late fourteenth century, Kilwa Kisiwani grew to encompass a population of several thousand, and some of its residents are thought to have founded a new settlement at Songo Mnara. Many communal wells, which, says Wynne-Jones, were vital hubs of urban life, supplied the people of Kilwa Kisiwani with fresh water. Songo Mnara’s groundwater, however, was more brackish. There were wells in the town center and at each of its six mosques, but for daily use, residents seem to have relied more on storing water. “There are cisterns in every house at Songo Mnara to capture and store rainwater,” Wynne-Jones says. “We don’t see that to the same extent at Kilwa.”

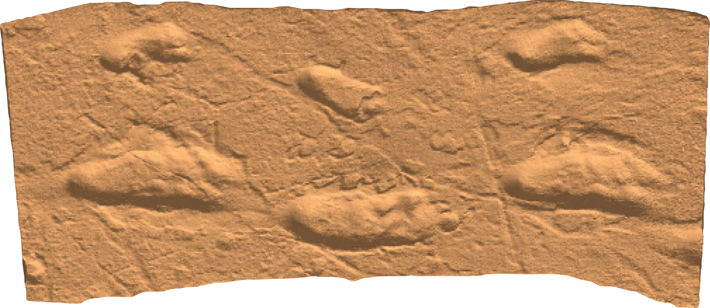

The Swahili put a great deal of effort into creating and beautifying spaces for washing. On either side of the steps of Songo Mnara’s central mosque, a pair of cisterns is connected by a conduit in which imported Chinese celadon bowls and plates, signs of prestige and wealth, were mortared into the bottom. Some scholars suggest the ceramics helped assess the water’s purity. “Looking at this green plate through the water,” Wynne-Jones says, “you could see if the water was discolored.”