In the village of Val in coastal central Norway, archaeologists excavated two medieval burials filled with weapons, jewelry, and skeletal remains in an unusually good state of preservation. One grave contained a man who lived in the eighth century a.d., accompanied by a knife, a whetstone, and a three-foot-long iron sword. “It’s very much a fully functioning sword,” says archaeologist Hanne Bryn of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). “It can do a lot of damage.”

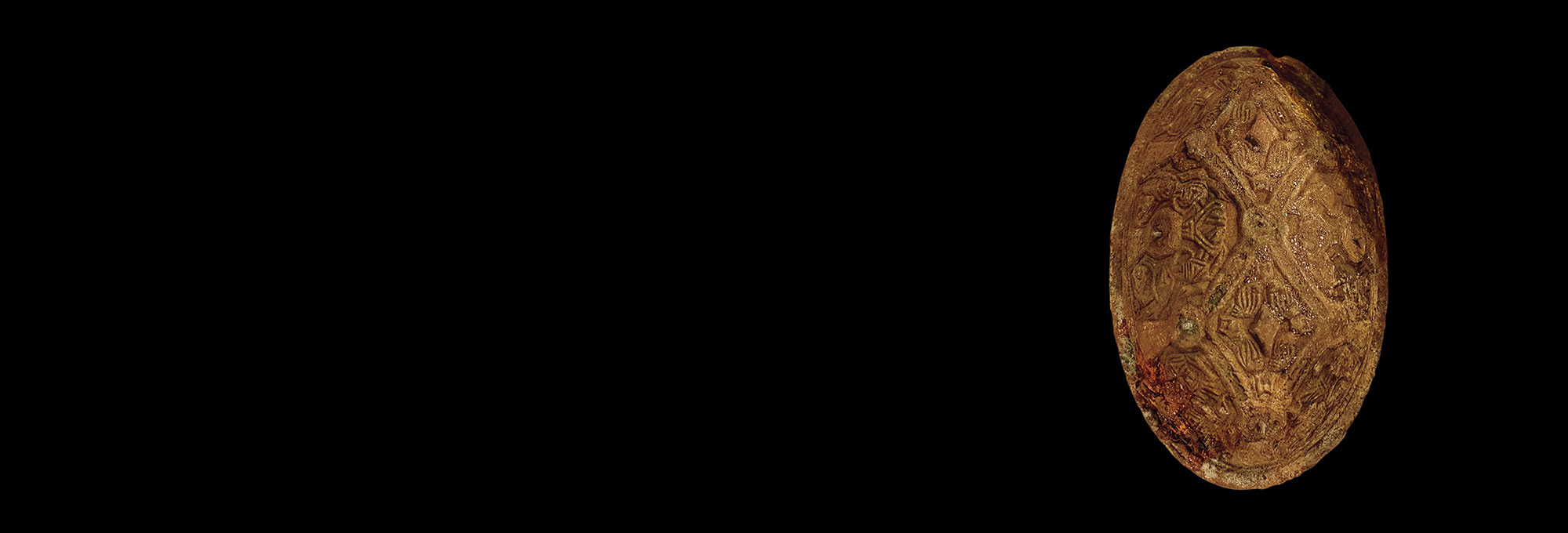

The second burial was found 30 feet from the first. It held a woman who lived on a farm at the site in the early or mid-ninth century a.d. Her grave goods included two intricately decorated oval copper alloy brooches and a smaller clasp at her neck. “For want of a better term, you could call these people middle class,” says archaeologist Raymond Sauvage, also of NTNU. “They owned their own land, but they worked hard throughout their lives.”

More surprising than the woman’s jewelry, however, were the scallop shells that had likely been placed on her cheeks—a practice without a known parallel in medieval Scandinavian archaeology. For medieval Christians, scallop shells were a symbol of the Camino de Santiago, or the Way of Saint James, a renowned pilgrimage route to northern Spain. “This region of Norway had little Christian influence that we know of,” says Sauvage. “But this was the early stages of Viking travels and discovery. They came into contact with Christianity, Islam, and perhaps Buddhism, too.”