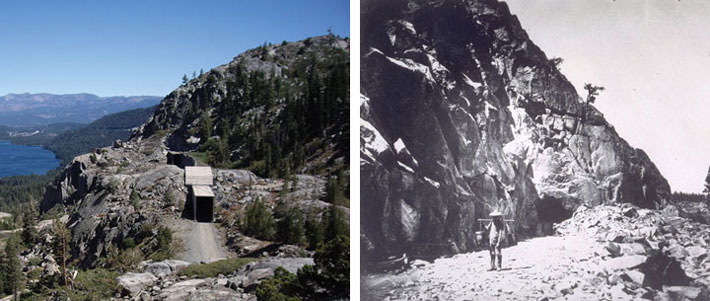

The Chinese first migrated to the West for the same reason most everyone else did: a shot at “Gold Mountain.” As their reputation for hard work (at low wages) grew, more Chinese came and found jobs on the railroads. Though Chinese immigrants worked in other professions, at the peak of railroad construction in the 1860s, up to 90 percent of the labor force was Chinese. They dug trenches and tunnels, built grades, and laid track from Utah to California, through the same country that had famously claimed the lives of the pioneer Donner Party just 20 years earlier. “The Transcontinental Railroad, arguably one of the most significant engineering feats in North American history, was constructed largely by Chinese workers,” says Stanford’s Voss. “It’s a dramatic example of the role that workers play in building countries and societies.”

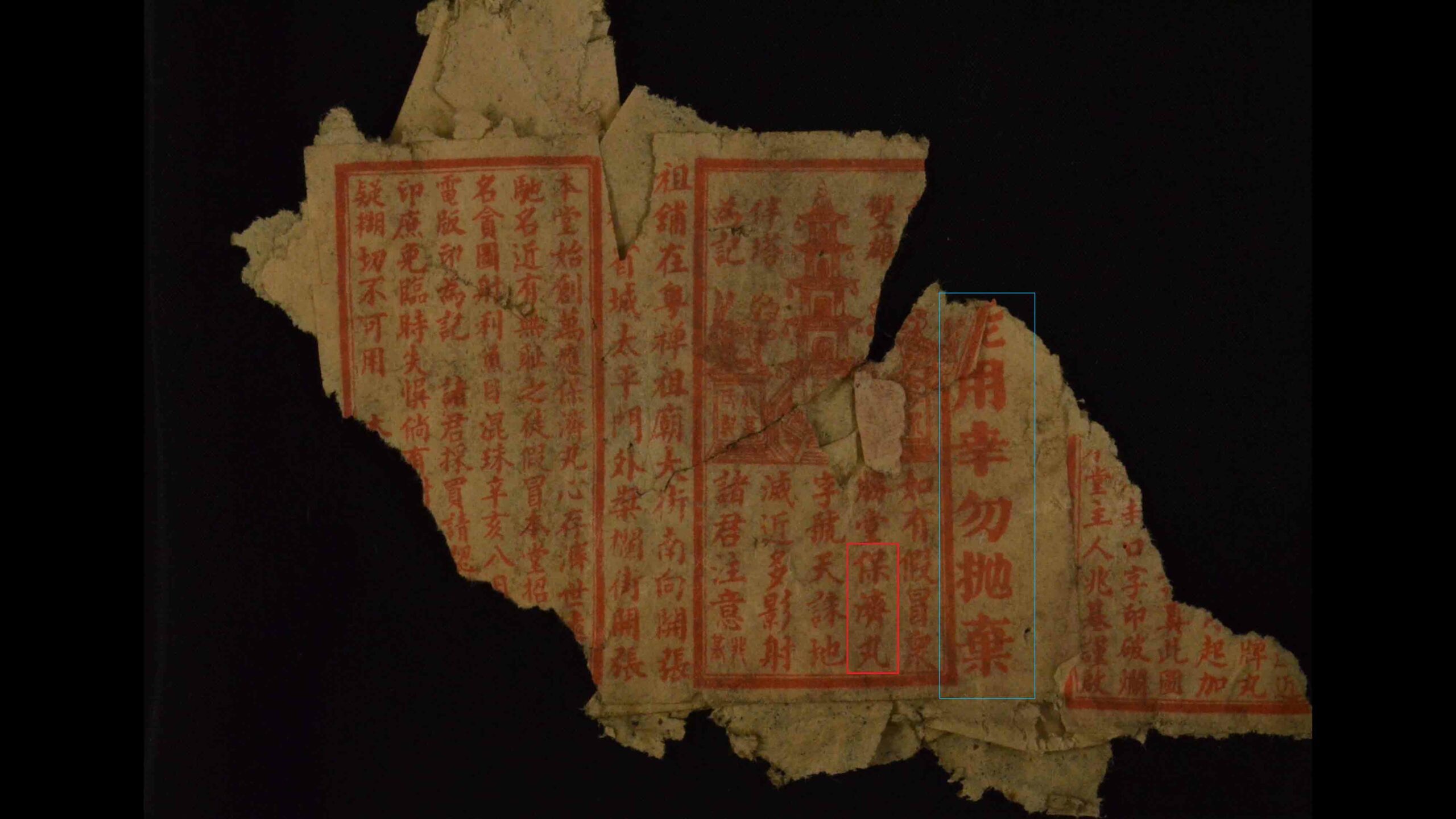

Many of the camps that housed Chinese railroad workers were temporary and have long been forgotten. But between 1865 and 1869, the Central Pacific Railroad pushed through Donner Pass in the High Sierras. At 7,000 feet, sometimes with up to 40 feet of snow pack, laborers, many of whom were Chinese, dug seven tunnels through solid rock. The work took four years, so some encampments there were more established and longer-lived than those elsewhere. John Molenda, a graduate student at Columbia University, has surveyed of a number of these camps, and Rebecca Allen and Scott Baxter of ESA studied one at Summit Pass in detail. “We wanted to know what they were bringing there to make themselves feel like they were at home,” says Allen.

Because tools and personal items probably traveled with the workers, the remains at these sites include some stone foundations and an array of potsherds, gambling pieces, and opium paraphernalia (perhaps used to treat injuries, aches, and pains). At the Summit site, Allen found the remains of a large roasting hearth, evidence of communal meals that may have helped build social bonds. Gambling pieces served a similar purpose, says Molenda. These men were away from their families or the relative comforts of a Chinatown for years at a time, and gambling was a way to create community. Besides, he adds, they wouldn’t have had much to lose: Chinese immigrants sent around two-thirds of their wages back home. According to Molenda, this sense of community, combined with a distinctly Chinese sense of duty and sacrifice, made them particularly effective and sought-after laborers. “They did as much as they could to make themselves as comfortable as possible within the constraint that what they were doing was not about having fun,” says Molenda.

They were so effective, in fact, that many American investors moved specific work gangs onto other projects after the completion of the railroad, and even sometimes protected them during surges of anti-Chinese sentiment. To the capitalists, the Chinese were a cheap, easily controlled labor force. To keep them that way, most investors supported anti-Chinese legislation, which thwarted any social mobility.

Much of this recent research is coming together in the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University, a cross-disciplinary effort involving historians, archaeologists, and other scholars. The project aims to create a digital archive of research materials, organize events and conferences, and make connections with institutions in southern China to unify the study of the railroad workers. According to Voss, archaeological director of the project, it is an opportunity for archaeologists in the field to examine new methods for studying a mobile, rapidly moving population. “This is a good project for archaeology,” she says. “This forces us to think differently about our data.”