Some time around 89 B.C.—the exact year is debated—Roman forces led by the general Lucius Cornelius Sulla laid siege to the city of Pompeii, likely in response to its residents’ agitation for full Roman citizenship. The walls on the city’s north side, where fortifications were particularly weak, still bear the impact marks of projectiles fired by the attacking Romans. In a number of areas inside the city walls, archaeologists have found catapult balls, small lead slingshot bullets, and machine-launched arrows known as scorpio bolts, all fired during the siege. “I don’t think anyone at the time was under any illusions that sustained bombardment would actually bring down the walls,” says archaeologist Ivo Van der Graaff of the University of New Hampshire. “It looks like one of the Romans’ tactics was to just fire munitions into the city to cause damage and, perhaps, lower morale.”

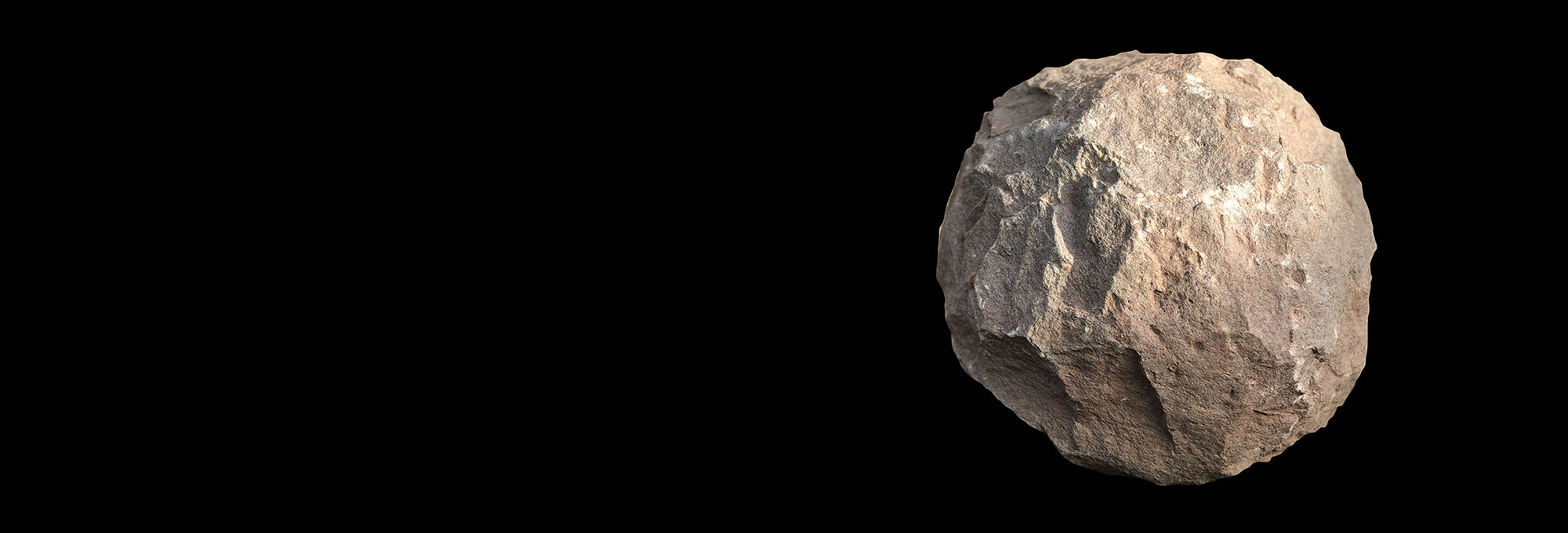

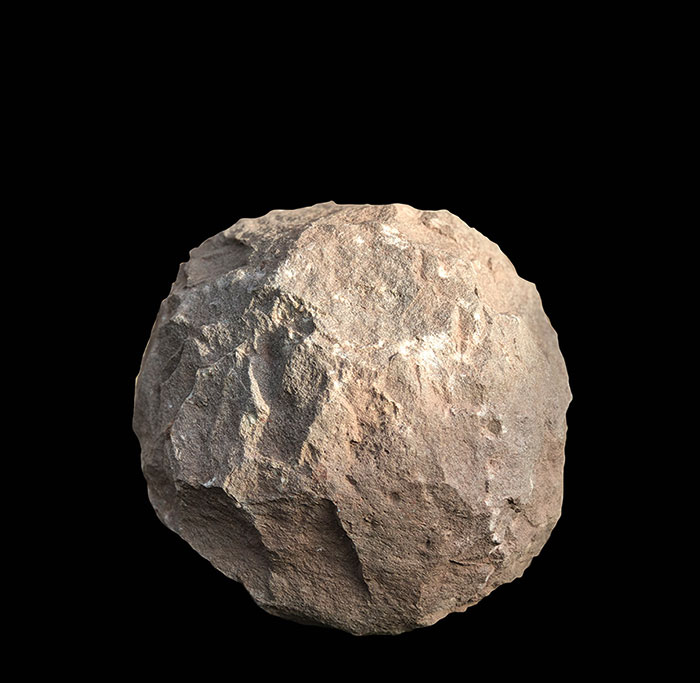

By the Middle Ages, engineers had perfected projectile-launching machines that could wreak havoc on even the most robust fortifications. During recent excavations at Hay Castle in southeast Wales, archaeologists unearthed a thirteenth-century stone ball catapulted from a siege machine called a trebuchet. The 63-pound stone is roughly the same size and weight as catapult balls excavated at other Welsh castles. “Only multiple impacts in the same place would demolish a wall,” says archaeologist Chris Caple of Durham University. “Trebuchet balls were deliberately created to be the same weight and size so they would all land in the same spot when fired.” Although researchers haven’t yet found other archaeological evidence of a siege at Hay Castle, documents record multiple fires and attacks during the thirteenth century, including one in July 1265, when the nobleman Simon de Montfort, King Henry III’s leading opponent, took the castle with the aid of allied Welsh princes.