A strip of forest with thick stands of trees including tall oaks and hickory separates the 8,300-acre Ashokan Reservoir and New York State Route 28, the main highway into the Catskill Mountains. Constructed in the early twentieth century, the reservoir provides 40 percent of New York City’s water. The forest surrounding the reservoir is maintained by New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), whose mission includes safeguarding the quality of the reservoir’s water—often called the champagne of American urban water. Most of these lands are open to hunters and fishers with permits or anyone who might take an interest in hiking through what seems at first glance to be pristine forest.

Archaeologist April Beisaw of Vassar College has spent years walking in these woods and concedes that they offer ample opportunities for birding and other ways of experiencing the Catskills’ native wildlife. But she also sees the forests through the eyes of someone who knows that the trees and undergrowth here conceal a traumatic historical event, the aftermath of which was the construction of the reservoir, which supplies an essential resource to the city’s eight million people today.

“This was a cemetery,” says Beisaw, as she enters an opening in the forest where a wetland and pond stretch over several acres. Once the final resting place of dozens of residents of the hamlet of Olive, the cemetery was one of 32 that were relocated to make way for the reservoir. “The water table moved up because of the reservoir,” she says, “and water now fills all those former graves.” In anticipation of the reservoir’s construction, New York City officials appropriated some 12,000 acres, leading to flooding of four hamlets and the relocation of eight more. In total, about 500 homes, 35 stores, 10 churches, and eight mills were destroyed. The city used eminent domain to condemn the properties, and owners were compensated at what many at the time maintained were below-market prices. The city’s Board of Water Supply also paid $15 per grave to friends or family of the deceased to disinter and remove their loved ones from cemeteries that stood in the reservoir’s way.

Beisaw walks past the former cemetery, now a pond that is home to egrets, herons, and other birds, and points out vanished homes and businesses that now exist only as faint remnants in the forested landscape. The land parcels are divided by stone walls and fence lines that only someone who has matched nineteenth-century maps with archaeological remains can now make out. Beisaw goes from site to site, walking amid the overgrown ruins and cellars that once belonged to the Orchard Grove Boarding House and to the homes of Sarah Bishop, Katherine Van Steenburgh, John Thiel, and Lewis Thiel. Each property had its own well, whose remains pockmark the landscape.

As a graduate student, Beisaw often hiked in the Catskills and recalls seeing the modest brown signs along Route 28 that mark the names of the former hamlets, such as Olive, Shokan, and Brown’s Station, that were inundated or forced to relocate by construction of the reservoir. She says that, like most visitors to this area, some 100 miles north of New York City, the signs made little impression on her. Not until she learned the scale of the reservoir’s human cost did she begin to wonder what might remain of the communities that were sacrificed to satisfy New York City’s growing thirst.

For the past decade, Beisaw and her students have been surveying and documenting ruins around the Ashokan Reservoir. “People are sometimes focused on what’s under the reservoir,” she says. “They imagine there are still towns underwater, but all those buildings were burned, and there is probably nothing left after more than a century.” But on land, working with members of the local community, she and her team have found considerable evidence of properties that existed within the “take line,” the outer limit of the land that the city bought and condemned. Of the 466 demolished buildings inside the take line, 306 were submerged and 160 remained above water. This means that the woods preserve evidence of a vibrant early twentieth-century landscape where more than 100 families made their homes. The champagne of water came with a high price that goes unrecognized today. “Urban water systems necessitate the destruction of places, but the city has no memory of this,” says Beisaw. “As archaeologists, we’re trying to make sure these people and communities aren’t forgotten.”

Since it was founded by Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century, New York City has struggled to supply its residents with water. For more than three centuries, its officials have looked ever northward for sources of water, and the creation of hydraulic infrastructure of growing complexity has often involved displacing communities with little political power.

For much of its early history, the city’s needs were supplied by Collect Pond, a freshwater reservoir recharged by rain and well water that was constructed just beyond the city’s northern outskirts at Wall Street. The pond lay near a community of formerly enslaved people who had been emancipated in 1827. By 1829, the pond and the nearby African American Burial Ground were both condemned and filled with soil as the city looked for more water. The levels of underground moisture at the site meant that for decades its ground was unstable and unsuitable for construction.

The Manhattan Company, founded in 1799 by Aaron Burr—who would become the United States’ third vice president in 1801—entered the market to supply Manhattan’s water by pumping it from various sites on the island and delivering it via a system of pressurized pipes. But the city’s need for potable water and for water to supply manufacturing industries continued to grow as the population exploded from 60,000 in 1800 to three million by 1900.

In 1832, a cholera outbreak caused by contaminated drinking water killed 3,500 people. It’s thought that 100,000 people—or two-thirds of the population at the time—fled the city to avoid the outbreak. City officials began to look beyond Manhattan Island for water supplies, settling on the Croton Watershed, some 40 miles north, as a new source. In a prelude to the construction of the Ashokan Reservoir, the city bought up mainly farmland to construct Croton Dam, which created a reservoir of 400 acres from which water could be routed south. Few people were displaced, and communities around the new reservoir remained largely intact.

A new reservoir in Manhattan was built in 1840 at what is now 42nd Street. It was constructed on the site of a former potter’s field, necessitating the removal of hundreds of bodies to an island in the East River. Water flowed to this reservoir from the Croton Watershed via a series of aqueducts. Soon the city’s needs once again outstripped the available supply. Two additional reservoirs were built in the 1850s at the center of the newly established Central Park, which itself was only created after removal of a community of impoverished people of African, Irish, and Native American ancestry known as Seneca Village.

For a time, the 20 million gallons of water per day that the Croton Watershed supplied the city was enough. But population growth meant that New York City went from consuming a few million gallons a day to 200 million gallons a day over the course of the nineteenth century. The expansion of the city to the boroughs of the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn only increased pressure on the Board of Water Supply to find a permanent solution to New York City’s water crisis. Time was of the essence, and the officials looked north once again, to the pure waters of the Catskill Watershed.

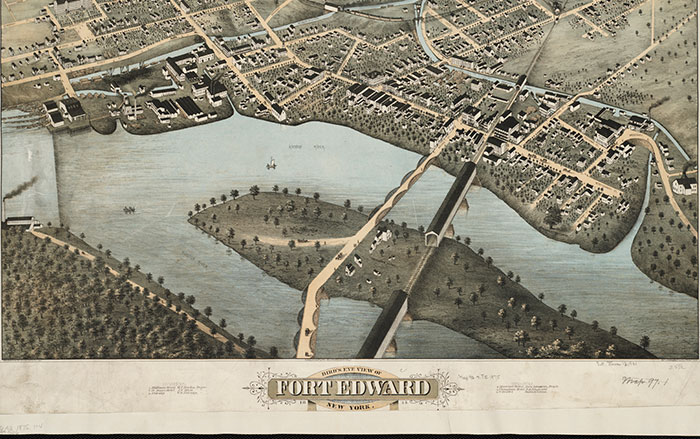

Some 10,000 people belonging to the Esopus tribe of the Algonquin Lenape are thought to have been living in the Catskill Mountains when Europeans began arriving in large numbers in the seventeenth century. Many lived along the Catskills’ main drainage, today known as Esopus Creek, which is fed by hundreds of streams that flow down from the region’s highest peaks before emptying into the Hudson River. By the 1740s, after a series of conflicts with Dutch and later English settlers, the Esopus were displaced, moving farther north. European farmers took up residence along Esopus Creek in a series of settlements destined to be consumed by the waters of the Ashokan Reservoir. These included the hamlets of Ashton and West Hurley in the town of Hurley and the hamlets of Olive, Olive City, Olivebridge, West Shokan, and Shokan in the town of Olive.

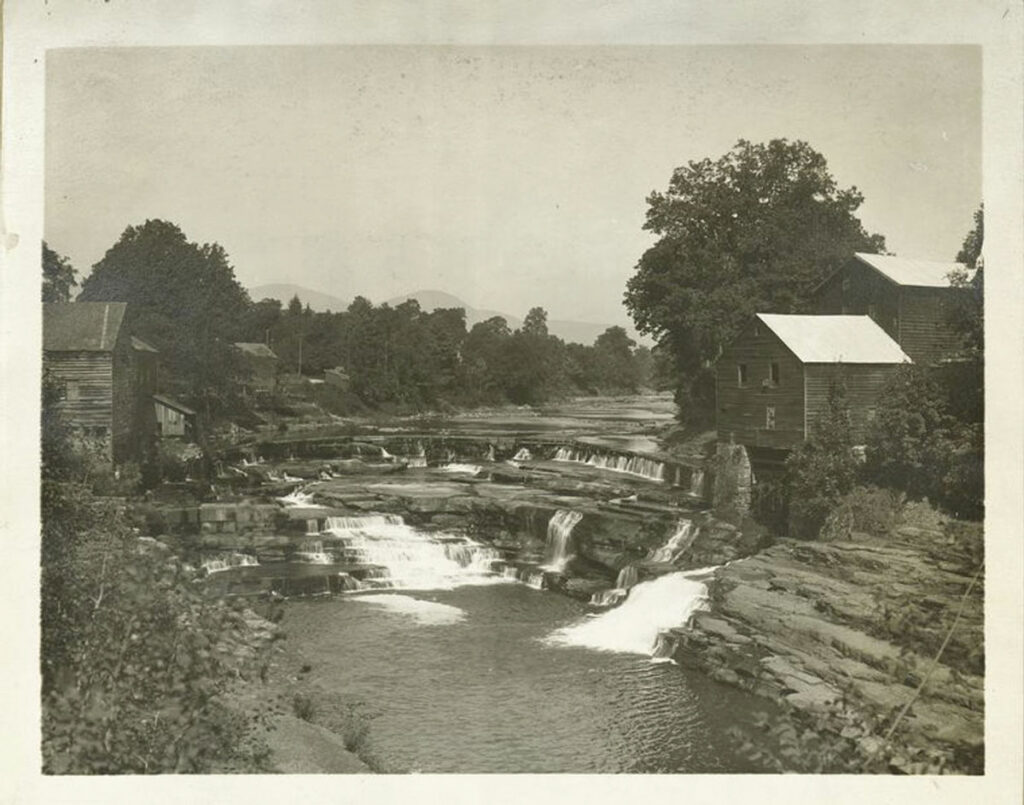

In addition to farming, many people living along Esopus Creek began tanning leather, an industry fueled by burning hemlock trees. By the mid-nineteenth century, the stock of hemlock trees in the area had been exhausted. The construction of the Ulster and Delaware Railroad along Esopus Creek in 1866 brought new opportunities, as New Yorkers eager to escape the city took advantage of the railroad to travel into the mountains. Known as the “gateway to the Catskills,” the town of Olive became a center for outdoor recreation. The number of boardinghouses in the area built to accommodate seasonal visitors grew dramatically. Local records show that among them were a “fresh air” farm in Shokan that was a destination for tubercular New York City children; the Bessie Jones Willowbrook boardinghouse, which could accommodate 150 guests; and other bucolic-sounding retreats, such as Sylvan Lake, Cool Breeze, and Maple Cottage. Beisaw estimates that around 10 percent of these boardinghouses were owned by women. At the time, keeping a boardinghouse was one of the few means by which women could build capital.

By 1901, the Board of Water Supply had determined that the most expedient way to supply the city’s increasingly desperate need for water was to dam Esopus Creek and construct underground aqueducts to transport the water south. City engineers began trespassing on private property in Olive without giving notice to local residents. They produced a 1903 report describing the lands around Esopus Creek as “practically a wilderness,” and in 1905, newspaper articles described the project as a fait accompli before residents had been officially informed. In spring of 1908, New York City officials began moving Olive residents from their homes, and construction of the reservoir began. The removal process took several years and was marked by chaos and uncertainty. Olive residents were offered sums on terms set by the city without any means of challenging the rates. Newspaper accounts and family oral histories indicate that not all residents went readily.

As of 1913, some 4,500 workers and their families had moved into temporary camps and settlements that were several times the size of the towns set to be destroyed. That year, the reservoir began to fill up. All the families who had lived along Esopus Creek whose property had been condemned had been removed and their homes and businesses burned to the ground. By 1915, the reservoir was complete, and it first reached its maximum capacity of 122.9 billion gallons. A technological marvel, it was the largest reservoir in the world at the time and had, temporarily at least, solved the city’s perennial water problem. The price that had been paid in terms of lost homes, farms, businesses, and communities, if it was given any thought by New York City bureaucrats or residents, was deemed well worth it.

Beginning in 2012, Beisaw and her students began studying every available map and record of the former Esopus Creek communities. While striving to make connections with locals who have deep roots in the community, such as an artist named Kate McGloughlin, Beisaw developed a plan to survey and record evidence of structures inside the Ashokan take line. “It’s often not the case that just because there is a historical or contemporary record of a community that we know all about it,” says Beisaw. “Mistakes are made, things aren’t recorded, and sometimes the archaeological record contradicts what written records we have.” As an example, she found quite early in her research that some signs marking the locations of vanished communities are more than a mile from where they should be.

After clearing her project with the DEP, Beisaw ventured into the woods surrounding the reservoir, mapping and photographing the stone foundations of houses, barns, and springhouses that were used to keep food cold before the introduction of refrigeration. More subtle remnants of the communities can be found in the forest as well. Stumps dating back to the nineteenth century show where people felled trees for lumber or fuel, metal buckets still lie where they were used to collect maple sap to make syrup, and the limits of apple and other fruit orchards that don’t exist on any map can be discerned by careful observation of the landscape.

Local residents such as McGloughlin often accompany Beisaw into the field. Sometimes they can confirm the location or extent of an orchard, or are surprised by the location of a house they had only heard about in family stories. Beisaw has digitized her data and shares it openly with the community. A six-foot-long map she has made of the landscape just prior to construction of the reservoir attracts a great deal of attention at local meetings.

Her work has extended to studying the landscape as it was impacted during and after construction of the reservoir. In the woods just south of the reservoir, the stone ruins of a rail system used to transport crushed local bluestone from a quarry to the dam site still stand. The remains include a complex system of chutes that carried quarried stones to trains waiting below. Two 11-foot-tall walls once held a wooden bin structure used to load railcars with the crushed stone. Beisaw and her students have mapped the remains of this system in great detail, creating a record of this long-overlooked feature of the reservoir’s infrastructure.

A few miles north of the reservoir, on an undeveloped piece of property on Ticetonyk Mountain owned by New York City and known as the Black Road Unit, Beisaw made a surprising discovery. While surveying the area, she found evidence of a farm—animal pens and the foundations of barns, outbuildings, and possibly a small house—that does not exist on any property records or maps of the area from the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Several maple trees at the site have holes that suggest they were tapped for syrup. Though the stone walls and other remains of the farm are difficult to date with precision, it seems likely they were built around the same time as the reservoir. The land is on a steep slope and its rocky soil must have made farming difficult. Beisaw speculates that it might have been cultivated by a farmer who lost land to the reservoir and attempted to start afresh nearby. If a farmer from Olive did try to work the land there, they had apparently given up by the time a map that included the property was drawn in 1942.

Beisaw has also attempted to track the female proprietors of Esopus boardinghouses in the historical record, to see if they were able to use the settlement money and any other capital they had to reestablish their businesses. So far, she has found that, out of 15 female owners, only two were able to set themselves up elsewhere. The construction of the reservoir, it seems, meant the end of their careers as entrepreneurs for most of these women.

The people of Olive were far from the only Americans to lose their homes and livelihoods to the construction of reservoirs, hydroelectric dams, and flood control measures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Historian Bob Reinhardt of Boise State University is attempting to record all the communities in the western United States that were inundated by government infrastructure projects. He and his team have built a database called the Atlas of Drowned Towns that contains dozens of towns and villages. He says the total number of communities lost likely runs in the many hundreds and is probably impossible to tally. “Thanks to April’s work, the communities lost to the Ashokan Reservoir are some of the best documented in the country,” says Reinhardt. “Each one has its own story to tell.” He points out that in his work he has found that some people living in communities in the American West where it was hard to make a living were happy to sell their land to the government and relocate. “That doesn’t seem to be what happened in the Catskills,” Reinhardt says. “In the course of her research, April has documented the emotional toll this took on the people, and that’s not something historians or archaeologists always do.”

Nestled in a grove of oak and pine in a valley less than two miles west of the reservoir, Bushkill Cemetery has six rows of identical one-foot-tall marble gravestones that mark 245 individual burials relocated from 19 Olive cemeteries. The gravestones are not carved with names or dates, but with alphanumeric codes such as LE 86 or ET 5. These codes refer to the original cemeteries the burials came from, such as the Lee Cemetery, which had 549 graves, or the Ennist Cemetery, where 176 individuals were once buried. Local historians and Beisaw have made an effort to identify all the people, including Civil War veterans, buried in Bushkill Cemetery and at other local cemeteries where remains were reburied. In some cases the records are too patchy to re-create, and, inevitably, some of the graves will remain anonymous.

On a recent morning, sunlight streamed through the tall oaks looming over the cemetery, illuminating the rows of perfectly aligned stones. Dry Brook Creek, which comes off Slide Mountain, the highest Catskill peak, flows just a few feet north of the cemetery. When it is running high, the sound of the water can drown out visitors’ conversations or birdsong. The stream rushes past the cemetery eastward toward Bush Kill, a larger creek that flows toward the reservoir. There it joins hundreds of other Catskill streams that help provide the many millions of gallons of water that daily flow south to New York City.