Halfway between Norway and Iceland, the Faroe Islands were long thought to be so remote that even the wide-ranging Vikings didn’t settle there until the ninth century A.D., once improved navigational technology allowed them to make long-distance sea voyages. New evidence unearthed by a team led by Durham University archaeologist Michael Church and National Museum of the Faroe Islands curator Símun V. Arge shows that another group actually settled the archipelago some 500 years before the Vikings arrived.

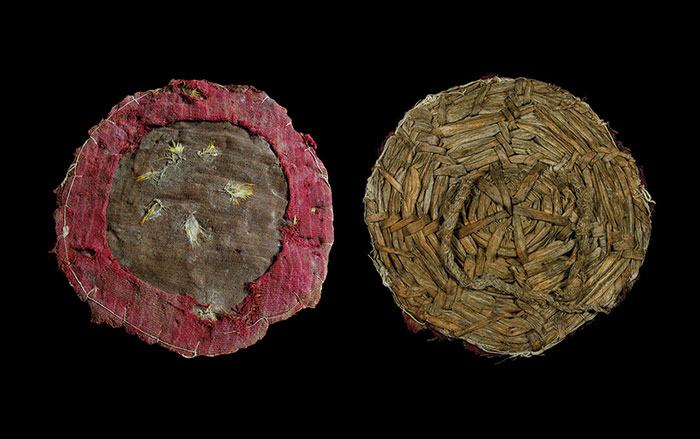

Excavating beneath the remains of a Viking longhouse, the team found two layers of burnt peat ash containing barley grains—unambiguous evidence of human presence. Radiocarbon dating of the ash layers shows that one was burned sometime between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D., and the other between the sixth and eighth centuries. The ash was probably taken from domestic hearths and then spread onto the sandy surface to control erosion, a common practice in the North Atlantic at the time.

But just who the early arrivals were remains a mystery. “All we know is that they cut peat and grew barley,” says Church. “They lived in sporadic, small-scale settlements, and the Viking invasion in the ninth century would have destroyed most of the evidence for them.” The settlers could have come from Scandinavia, Scotland, the Shetland Islands, or even Ireland, all places where early medieval people grew barley and used peat for fuel. Church notes that sixth-century Irish monks left accounts that mention islands that could be the Faroes, which lie some 600 miles to the north of Ireland. “Monks of that era were known to make long journeys in search of solitude to get nearer to God,” says Church. “The Faroes would certainly have offered them that.”