On November 13, A.D. 1002, Æthelred Unræd, ruler of the English kingdom of Wessex, “ordered slain all the Danish men who were in England,” according to a royal charter. This drastic step was not taken on a whim, but was the product of 200 years of Anglo-Saxon frustration and fear. Vikings, who had long plagued the Isles with raids and wars, had taken over the north and begun settling there. Concerns were growing that they had designs on Æthelred’s southern realm as well.

Æthelred’s order led to what is known as the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, named for the saint’s feast day on which it fell. The event has long been cloaked in mystery and misinformation. Archaeology, so far, has had little to offer in the matter of what actually happened and how many people died that day, but two mass burials recently unearthed are beginning to expose this turbulent period around the end of the first millennium. Could they be the first archaeological evidence of the massacre? Or might they offer a glimpse into some other aspect of the conflict between Anglo-Saxons and Vikings? Archaeologists are examining a trail of clues, including historical sources, wound patterns, and isotopic analysis of teeth, to put what was no doubt a violent series of deaths into perspective.

The Vikings of popular imagination were raiders and pillagers in longboats and (mythical) horned helmets, but the term “Viking” also refers to the farming, trading, crafting, exploring Scandinavian culture from which these raiders came. The Vikings that attacked and settled England and France were, for the most part, from or identified with Denmark. (The Norwegians went north and west, and the Swedes east, though there was a lot of movement of people among the Viking territories.) Viking raids in England began in the late eighth century A.D. and led to the fall of England’s northern kingdoms. Many of the Danish settlers were warriors granted land as a reward for success in battle. The only Anglo-Saxon holdout was Wessex, a powerful and wealthy kingdom that controlled most of the south of the island. An 878 treaty established the boundaries of Wessex and the Danish-controlled area, known as the Danelaw.

There is much discussion among historians about the nature of the relationship between the Anglo-Saxons and the Danes. Many of the new settlers had once been warriors, but they eventually brought along their families. The Danes farmed, traded, and even intermarried with the Anglo-Saxon population, and their cultural influence can be seen in language, place names, and surnames that persist in England today. Some historians argue that there weren’t all that many Danish settlers and that they assimilated many local traditions and beliefs. But there was likely some tension and resentment between the Danish settlers and the Anglo-Saxons (who, ironically, were also descended from continental invaders).

Relations between Wessex and the Viking superstate of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark had deteriorated by the time of Æthelred’s reign. Peace was purchased with tens of thousands of pounds of silver—protection money called Danegeld—paid to the Viking king, Sweyn Forkbeard. The threat of more raids, armies, and conquests from the Viking homelands continued to vex Æthelred. In 1002, rumors reached the king, who would come to be known as “Æthelred the ill-advised,” stating that the Danes were planning his ouster. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a somewhat biased tenth-century account, “it was told the king, that they would beshrew him of his life, and afterwards all his council, and then have his kingdom without any resistance.” His reaction was to order the death of every Danish man on the island’s soil.

Contemporary historians believe that the massacre was limited to recent migrants and members of the Danish elite outside the Danelaw (where a massacre would have been unlikely), but no one knows just how many people died. Politically, the order achieved little for the king. Its main outcome was the alienation of Danes working for him and, the following year, a brutal retaliation by Forkbeard.

According to later literary sources, Forkbeard was particularly enraged by the death of his sister, her husband, and their child in the massacre. The story goes that they and other fleeing Danes had sought sanctuary in St. Frideswide’s Church in Oxford (now Christ Church Cathedral). As Æthelred recorded in a royal charter, “When all the people in pursuit strove, forced by necessity, to drive them out, and could not, they set fire to the planks and burnt, as it seems, this church with its ornaments and its books.” Those who did not die inside, sources state, were killed by their pursuers as they tried to escape.

Almost exactly 1,000 years later, archaeologists in England discovered two mass burials containing the remains of dozens of young men who had been slaughtered or executed. Are these bodies the first archaeological evidence for the St. Brice’s Day Massacre? Or are they victims of another sort?

The first mass grave was found in 2008 by archaeologists digging on the grounds of St. John’s College. One of the University of Oxford’s richest and oldest colleges, St. John’s was about to build new student accommodation, and since British planning regulations require an archaeological assessment ahead of new construction, a team from Thames Valley Archaeological Services (TVAS), directed by Sean Wallis, was called in.

The team first found the previously unknown remains of one of Britain’s largest Neolithic henges, almost 500 feet in diameter. The find immediately changed the perception of prehistoric Oxford from a rather insignificant ford across the Thames to potentially one of the most important ritual sites in southern England. The henge’s eight-foot-deep ditch had become, by the medieval period, a dump for waste, including broken pottery and food scraps. It was there, in the garbage-filled ditch, that the team found the remains of 37 people.

All the bodies in the grave appear to have been male (though two were too young for their sex to be determined), and most were between 16 and 25 years old. As a group, they were tall, taller than the average Anglo-Saxon at the time, and strong, judging by the large muscle-attachment areas of their bones. Despite their physical advantages, all these men appear to have met violent ends. One had been decapitated, and attempts at decapitation had seemingly been made on five others. Twenty-seven suffered broken or cracked skulls. The back and pelvic bones of 20 bodies bore stab marks, as did the ribs of a dozen others. A number of the skeletons had evidence of charring, indicating that they were burned prior to burial.

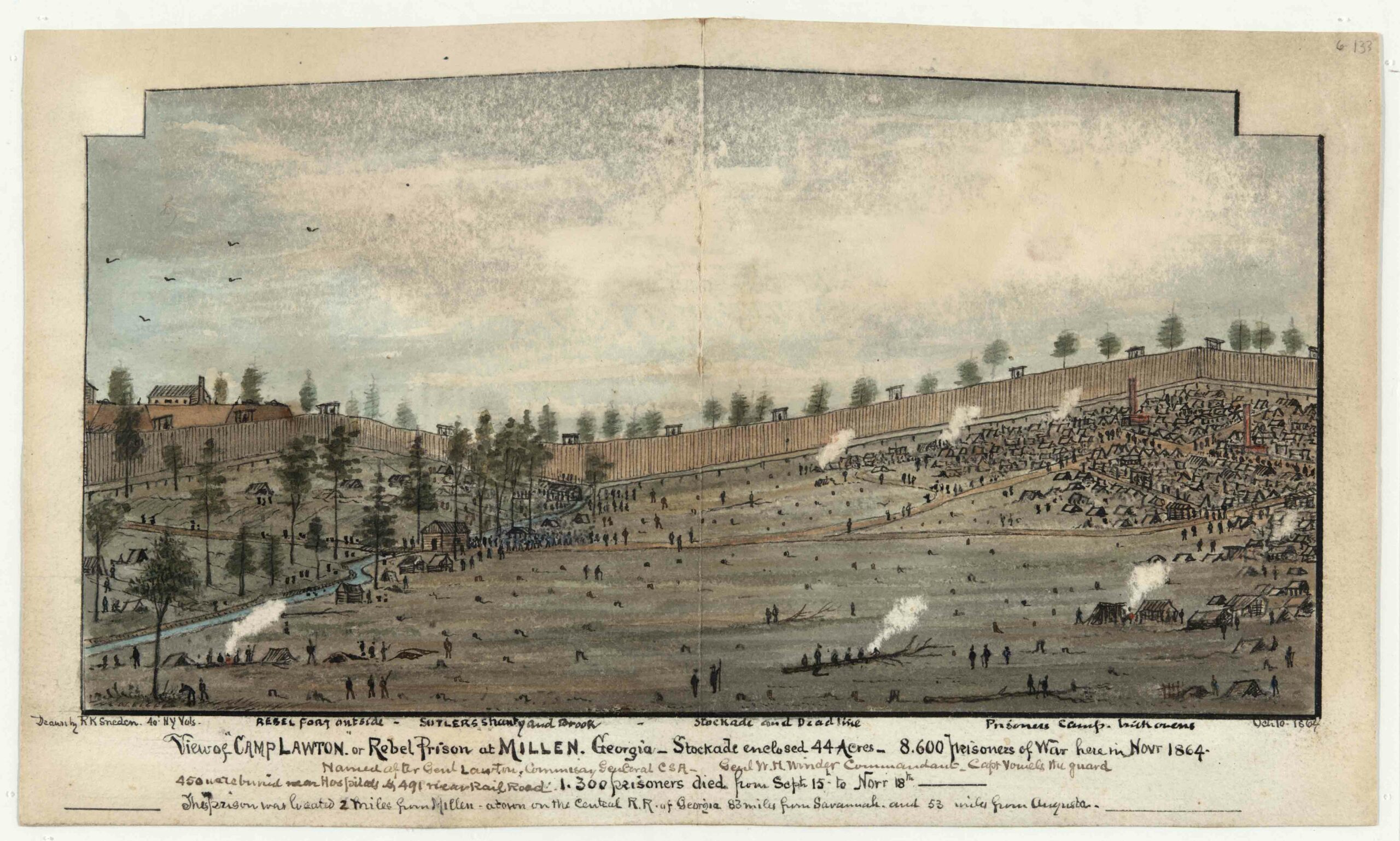

EXPAND

Burial Pit, ca. 960–1020, St. John's College, Oxford

Bone specialist Ceri Falys of TVAS began piecing together the fragmented skulls and skeletons. Osteologists such as Falys employ the skills and techniques of forensic pathologists, and can tell from damage done to bones not just how people died, but also how they were attacked, from what direction, and even with what level of ferocity. Falys saw that the damage to the bones revealed a frenzied attack, but not the sort one would expect from a traditional medieval battle. Instead, her meticulous work revealed that many of the men appear to have been attacked from all sides. For example, one victim suffered wounds to both his skull and pelvis, suggesting he had been attacked both from behind and from the side, by at least two different people. “The injuries I observed were not the result of men involved in hand-to-hand combat,” says Falys. “In such cases, we would expect to find cut marks on the forearms and hands as the person raises their arms to defend. Instead, I believe these wounds were the result of undefended people running away from their attackers.”

Radiocarbon analysis of the bones dates them to around 960 to 1020—England’s later Anglo-Saxon period, including the reign of Æthelred. Wallis and his excavation team were convinced, in part because of the evidence of the burning of the remains, that they had discovered a mass grave from St. Brice’s Day 1002.

In 2009, to extract yet more information from the bones, scientists from the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art at the University of Oxford, led by Mark Pollard, carried out chemical analysis of collagen from the bones and enamel from the teeth of some of the individuals. The techniques included carbon and nitrogen stable-isotope analysis of bone collagen, which is widely used to study diet and migration, and strontium and oxygen isotopic analysis of dental enamel, a powerful indicator of where an individual spent his or her early life. Pollard concluded that the victims had diets with a substantial amount of seafood—somewhat more than is found in the diets of the local population at the time. This supported the notion that the dead were indeed foreign to the British Isles. Although it was obvious that the men had been slaughtered, Pollard did not feel there was enough evidence to prove that they were victims of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre.

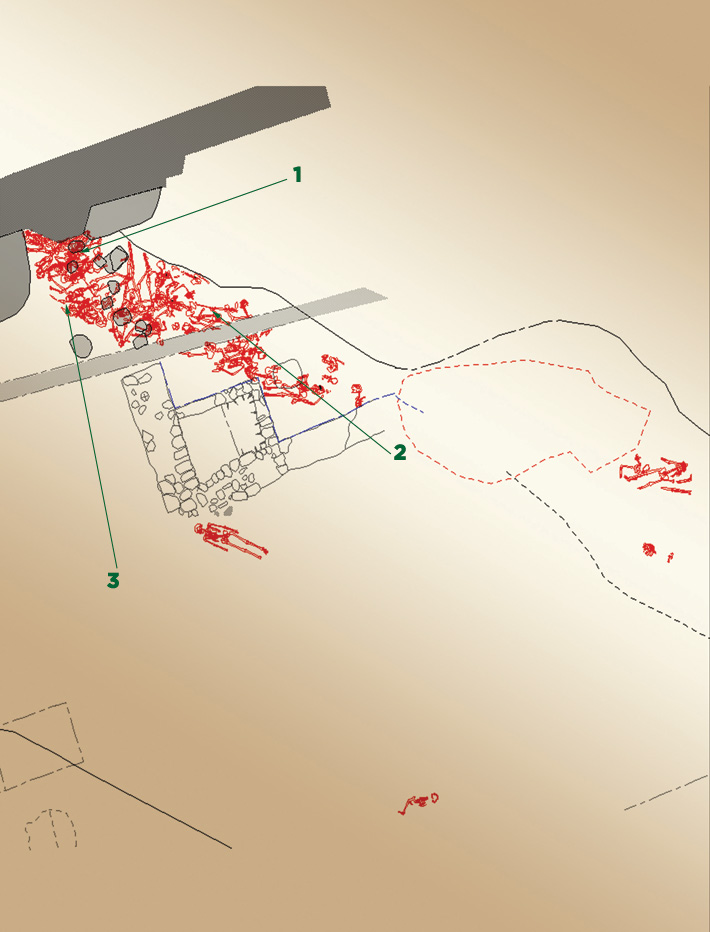

The investigation took a twist when Pollard compared his analysis with research on a second set of early medieval skeletons. These other bodies had been found in June 2009, in a burial pit at Ridgeway Hill, near the seaside town of Weymouth in Dorset, southern England. Weymouth was then set to host the sailing events for the 2012 Olympic Games, so a relief road was being built around the town to handle traffic. A team from the independent archaeological organization Oxford Archaeology discovered a pit similar to the one in Oxford, containing the remains of 54 men who had met violent ends. Almost all had been young and fit when they died. In this case, each of them had been beheaded, and a stash of skulls was found buried separately. Angela Boyle, senior osteologist at Oxford Archaeology, directed the skeletal analysis and found that most of the men were wounded exclusively in the upper spine and cranial area, a pattern consistent with execution. However, Boyle observed very few other injuries, such as defensive wounds to the arms or hands, again suggesting the men had been summarily killed, rather than having fallen in battle.

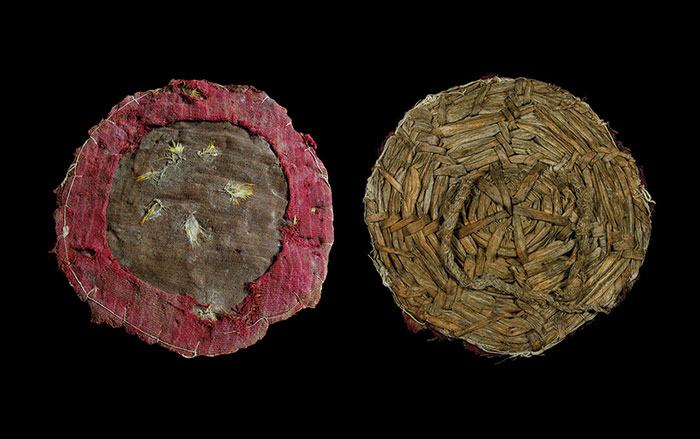

She also discovered that one of the men had incisions in his teeth, a painful dental modification associated with Viking mercenaries. Some scholars believe that such dental incisions may have been filled with colored pigment to make them appear more frightening. This practice could explain the origin of nicknames such as “Bluetooth.” One man who carried this moniker was Harald Bluetooth, described in two Nordic sources as founder of the Jomsvikings, a group of warriors so notorious across Europe that they spawned their own saga. “I am content to die as are all our comrades. But I will not let myself be slaughtered like a sheep,” says one Viking in the Jomsviking saga. “I would rather face the blow. Strike straight at my face and watch carefully if I pale at all.”

According to Britt Baillie of the University of Cambridge, who has been working on the interpretation of the burial, the men there are more likely to have been inspired by the saga than they are to have been characters in it. “The Jomsviking story seems to have been in active circulation around the turn of the millennium, so my theory is that the men on the Ridgeway wanted to emulate the bravery depicted in the saga, although alleged ‘Jomsvikings’ are said to have been operating in England at the time,” she says. “But how they were rounded up without suffering more wounds is unknown.”

Evidence from the burial suggests that these men were being made examples of. They were beheaded in a peculiar way—from the front, facing the blow. They were executed by sword instead of by ax, and had been stripped—both activities that are associated with the execution of high-status warriors. In fact, the execution may have had an audience, having taken place at a prominent point where the Roman road and the Ridgeway path intersected. Because fewer skulls than bodies have been found, some heads may have been displayed on stakes at the site.

Isotopic analysis of these remains by Jane Evans and Carolyn Chenery at NERC Isotope Geosciences Laboratory, part of the British Geological Survey, shows that the men originated from a variety of places across the Viking territory. The isotopes in their teeth confirmed that, like the remains found in Oxford, the men grew up in countries colder than Britain, with one individual thought to be from north of the Arctic Circle, and that the men had eaten a diet high in protein, another marker of Scandinavian origin. Radiocarbon analysis returned dates of between 980 and 1030 for their deaths—broadly contemporary with the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. Here was a group that may or may not have been victims of Æthelred’s order. Regardless, they were clearly not settlers, but rather Viking mercenaries or warriors of some sort.

Pollard saw undeniable parallels between the Oxford and Weymouth mass graves. The collagen isotopic results are comparable, and the sex, age, and stature of the dead are similar. The dead were all foreign migrants. To Pollard the similarities between the two groups were too much to ignore. He believes the Oxford group was, like the Weymouth group, a collection of professional warriors and raiders—not “innocent” settlers cut down indiscriminately. Though the men buried in Oxford had not been ritualistically executed, they seem to have been killed in a frenzy or rounded up and executed, most likely as revenge for prior raids. “For students of history,” says Pollard, “it is perhaps disappointing that we cannot with certainty corroborate the story of the massacre in Oxford on St. Brice’s Day, at least not with these remains.”

However, the Oxford site’s chief archaeologist, Wallis, remains convinced that the Oxford men were killed by Æthelred’s order in 1002. “We found no defensive wounds. If these were active and professional mercenaries, then why were they unarmed, and why did they not protect themselves? They also seem to have been killed while running away, and some were then exposed to burning, which is precisely what would have happened in the St. Brice’s Day Massacre,” he explains. “At some point the Oxford men may well have been soldiers, and some, probably all, were unambiguously foreign. But, as the historical documents say, these were folk who were deeply resented for having first raided, and then settled among the Saxons.”

To Wallis and his colleagues at TVAS, the men buried in Oxford may have had warriors-turned-settlers among them, who were caught off guard and pursued by an angry mob. He believes they were quite unlike the group of mercenaries or warriors ritualistically executed at Ridgeway Hill in Weymouth.

However, the story remains complicated. Baillie even questions the widespread assumption that the Weymouth men were, in fact, mercenaries at all. “The problem with the Weymouth burials is that the men did not have many old wounds, consistent with having been engaged in earlier battles,” she says. “One would expect that mercenaries would have defended themselves, yet very few of the skeletons display such wounds. Perhaps they were hostages taken from a larger battle. However, it is also possible that those men were also victims of the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, but that their killings were simply carried out in a much more orderly fashion. We will never know for certain.”

Clearly both sets of burials were acts of vengeance, products of the resentment that had built among the Anglo-Saxons as they saw their erstwhile attackers become, in some cases, their neighbors. Archaeology has offered some insight into the period, but for now, the story surrounding the St. Brice’s Day Massacre will remain contested.