NEW ZEALAND

NEW ZEALAND: On private Great Mercury Island off the northeast coast, archaeologists are excavating an early Maori site—dating to the second half of the 14th century, perhaps just decades after Polynesian seafarers first arrived. It appears to be a small fishing settlement, marked by thousands of stone artifacts, as well as fishhooks made from sea mammal teeth and the bones of moa, the large native birds that were hunted to extinction 100 years after human arrival. A number of oceanside sites such as this one are at risk from coastal erosion. —SAMIR S. PATEL

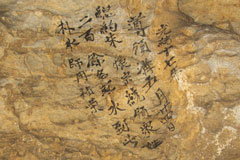

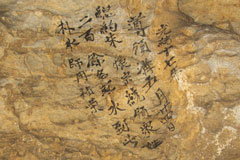

CHINA

CHINA: For 500 years, residents near the Quinling Mountains in Shaanxi Province went to Dayu Cave to collect water and—when times were tough—pray for rain. They also left inscriptions about those times that, combined with the isotopic and elemental content of the cave’s rock formations, provide a unique historic and geological record of climate and rainfall. Seven separate drought events are recorded in both the inscriptions and deposits, some associated with major social instability. A scientific model suggests that the region is due for severe drought again soon. —SAMIR S. PATEL

KAZAKHSTAN

KAZAKHSTAN: Following tips from local officials, archaeologists working at the Koitas cemetery recently excavated a kurgan, or burial mound, which had clearly been looted in antiquity. They found scattered bones from an elite Scythian burial, including a vertebra with an entire 2.2-inch-long bronze arrowhead embedded in it. Bone growth suggests that—defying the odds for a spinal injury victim in the Iron Age, or any age, for that matter—the Scythian survived for some time after the blow. —SAMIR S. PATEL

ISRAEL

ISRAEL: The Hellenistic site of Maresha, occupied between the 4th and 2nd centuries b.c., might be where chickens became chicken. Jungle fowl had been domesticated millennia earlier in Asia and had already spread across Europe, but in small numbers, usually as fighting cocks or for ritual purposes. But at Maresha there are thousands of chicken bones, which tells researchers that the site is key to understanding how the birds came to be regarded as food and bred in large numbers a hundred years before the chicken-chomping craze swept across Europe. —SAMIR S. PATEL

SOUTH AFRICA

SOUTH AFRICA: Sidubu and Blombos are two landmark Middle Stone Age sites separated by more than 600 miles. A new, detailed analysis of certain stone tools from both sites reveals that the people at each used the same types of tools around 71,000 years ago, but that there are differences in how they were made. By a few thousand years later, little difference is seen in tool manufacture, suggesting that these groups shared a common tool technology, and then drifted apart and developed their own traditions, before returning to the same methods, perhaps due to increased cultural contact. —SAMIR S. PATEL

SWEDEN

SWEDEN: The naturally mummified body of Bishop Peder Winstrup, interred in Lund Cathedral, is one of the best-preserved sets of 17th-century remains on the continent. A new study of Winstrup, including CT scans, reveals that he had tuberculosis, pneumonia, atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, gallstones (from a fatty diet), and cavities (from a sweet diet)—and that he had been, predictably, bedridden for some time before death. Investigators also found, quite unexpectedly and as-yet-unexplained, the remains of a 4- or 5-month-old fetus hidden under his feet. —SAMIR S. PATEL

PERU

PERU: Among the hundreds of sets of human remains excavated from a historic cemetery in Eten, as part of an ongoing regional project, were the remains of a teenage girl whose skeleton had dozens of extra teeth and bone fragments in her abdomen. Close examination revealed that, rather than a sacrificed animal or unborn fetus, the mass was an ovarian teratoma, or a cyst composed of different kinds of tissue, such as hair, bone, and teeth. It is thought to be only the third known ancient example of such a condition. —SAMIR S. PATEL

NORTH CAROLINA

NORTH CAROLINA: Researchers on the oceanographic vessel Atlantis were using an automated underwater vehicle to scan for a mooring they had lost in a previous research season. They saw a line and dark patch on the sonar, and sent the submersible Alvin to investigate. They didn’t find their mooring a mile down, but rather an unknown shipwreck, with artifacts including bricks, bottles, a sextant (or possibly octant), and pottery that may date it to the time of the American Revolution. —SAMIR S. PATEL

ARIZONA

ARIZONA: Throughout the Southwest, archaeologists have found small fiber bundles, called quids, that were chewed by prehistoric Native Americans, but it is not known why they were chewed. Researchers have examined a collection of quids excavated from Antelope Cave in the 1950s. Ninety percent of those studied, used by Ancestral Puebloan people more than 1,000 years ago, contained bits of wild tobacco. Because they were found among household trash, it is mostly likely these quids were chewed for pleasure rather than some ritual purpose. —SAMIR S. PATEL

ALASKA

ALASKA: A crew of 75 manned the doomed last voyage of Neva, a ship sailing from the Siberian port of Okhotsk to Sitka in the fall and winter of 1812–1813. Of those, 26 survived a perilous voyage, a violent wreck, and a harrowing, frigid month on shore awaiting rescue. A multinational team has been excavating the survivor camp and has found artifacts from the wreck, such as sheet copper, metal spikes, and gunflints, that the crew repurposed in their struggle to survive an unfamiliar and dangerous wilderness.