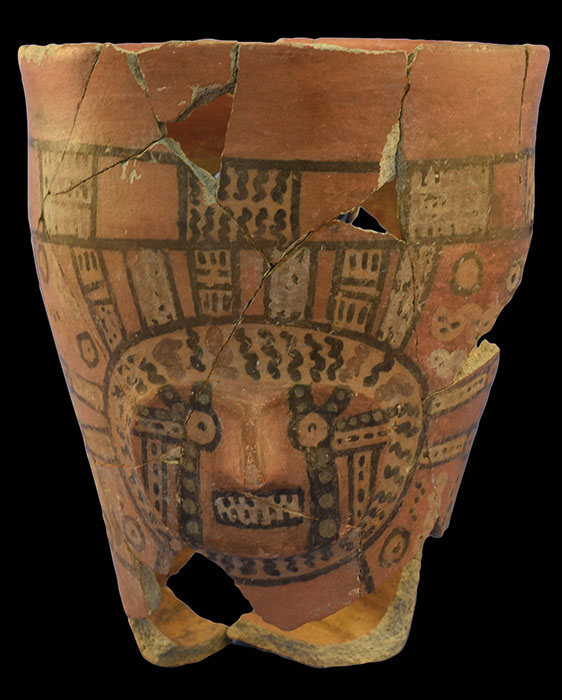

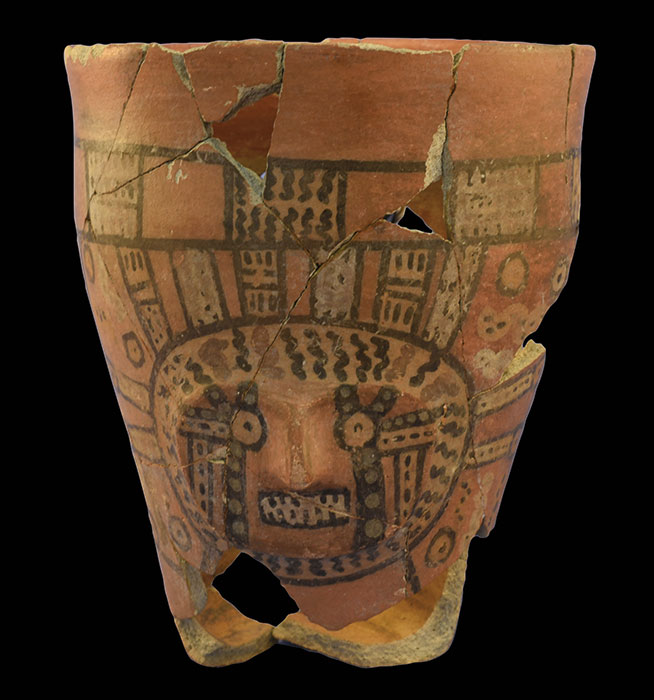

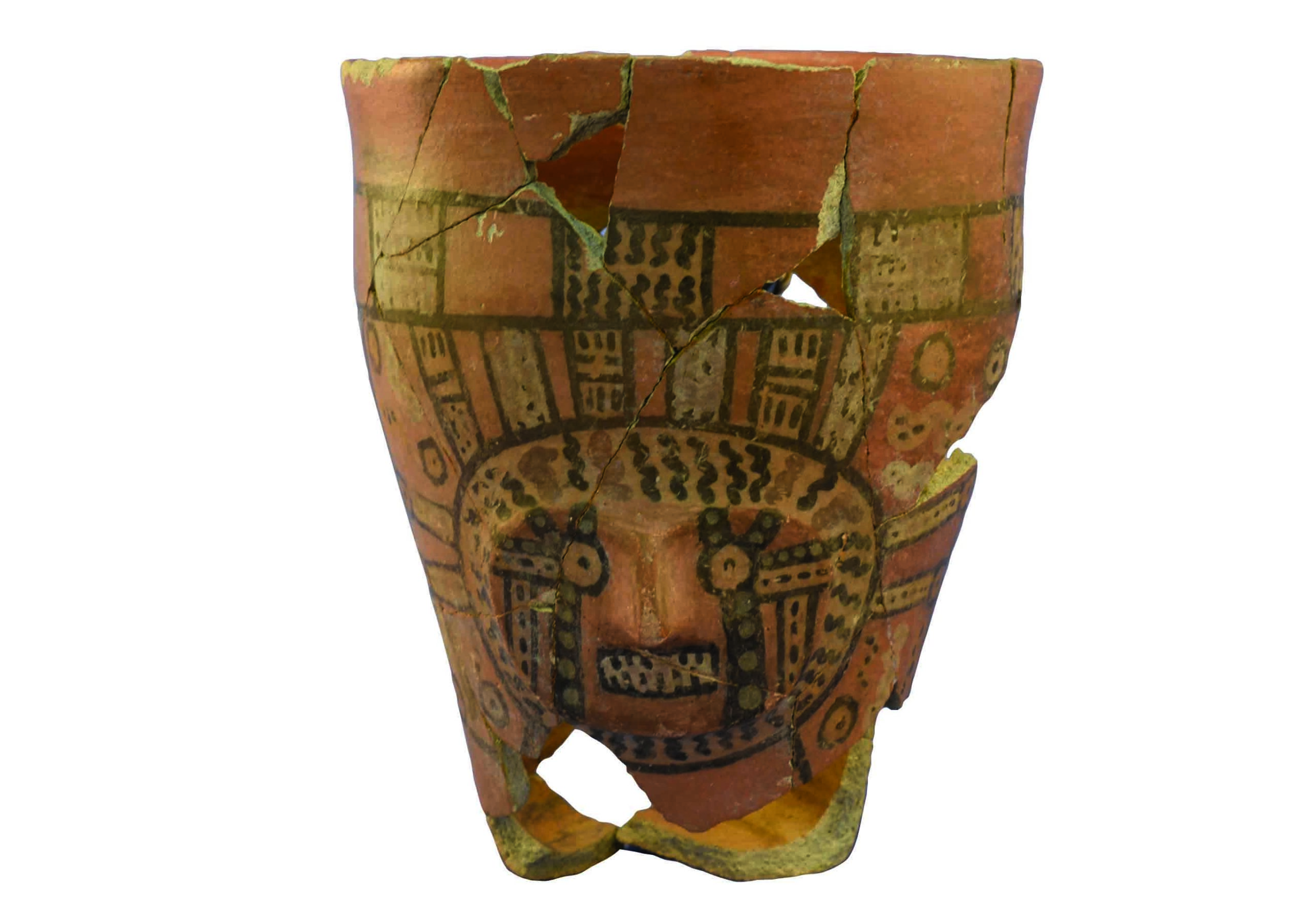

High atop a mountain in southern Peru, leaders at the remote administrative center of Cerro Baúl once entertained local elites with elaborate feasts that helped sustain the Wari Empire from about A.D. 600 to 1000. Central to these gatherings was the ceremonial drinking of chicha, a typically corn-based fermented beverage. Based on the size of the spaces where the feasts took place, archaeologists think that they held 50 to 100 guests who imbibed chicha from vibrantly painted ceramic cups. These cups ranged in size to reflect the status of the drinkers and were decorated with images of Wari heroes and gods, such as the Front-Facing Deity, and more local stylistic flourishes, including llamas adorning the deities’ faces. “One of the most effective ways to bring local elites into the hierarchy of the empire was through drinking Wari beer the Wari way,” says archaeologist Donna Nash of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, who codirects excavations at Cerro Baúl with archaeologist Ryan Williams of the Field Museum. “Many of the stories, songs, and ideas that went with that probably would have been expressed using the iconography on the vessels guests were drinking from.”

Because Cerro Baúl was a provincial outpost on the empire’s edge, the Wari relied on local resources and on-site brewing to maintain a steady flow of chicha. Nash and Williams have unearthed a large brewery where high-status Wari women ground, boiled, and fermented corn and other ingredients to produce the beverage. Analysis of residue extracted from drinking cups, serving vessels, and oversize storage jars from the brewery’s fermentation room indicate that the drink was likely a mixture of corn and molle, or Peruvian pepper tree berries, whose seeds the archaeologists found in large quantities in the brewery’s trash pits. Although the Wari at Cerro Baúl didn’t have direct access to fresh water, the region’s temperate climate was a boon for chicha production, even during more arid periods. “Molle berries produce year-round in this environment,” says Williams. “Corn can be double or triple cropped, so you can get two to three times the corn from a single year’s harvest.”

The Wari’s self-sufficiency ensured that feasting events could continue regardless of political disruptions or trade delays elsewhere in the empire. The archaeologists have determined that even the cups the Wari used were made in a ceramic workshop on the mountaintop using high-quality clay from a source they controlled across the valley, rather than imported from the distant imperial capital.