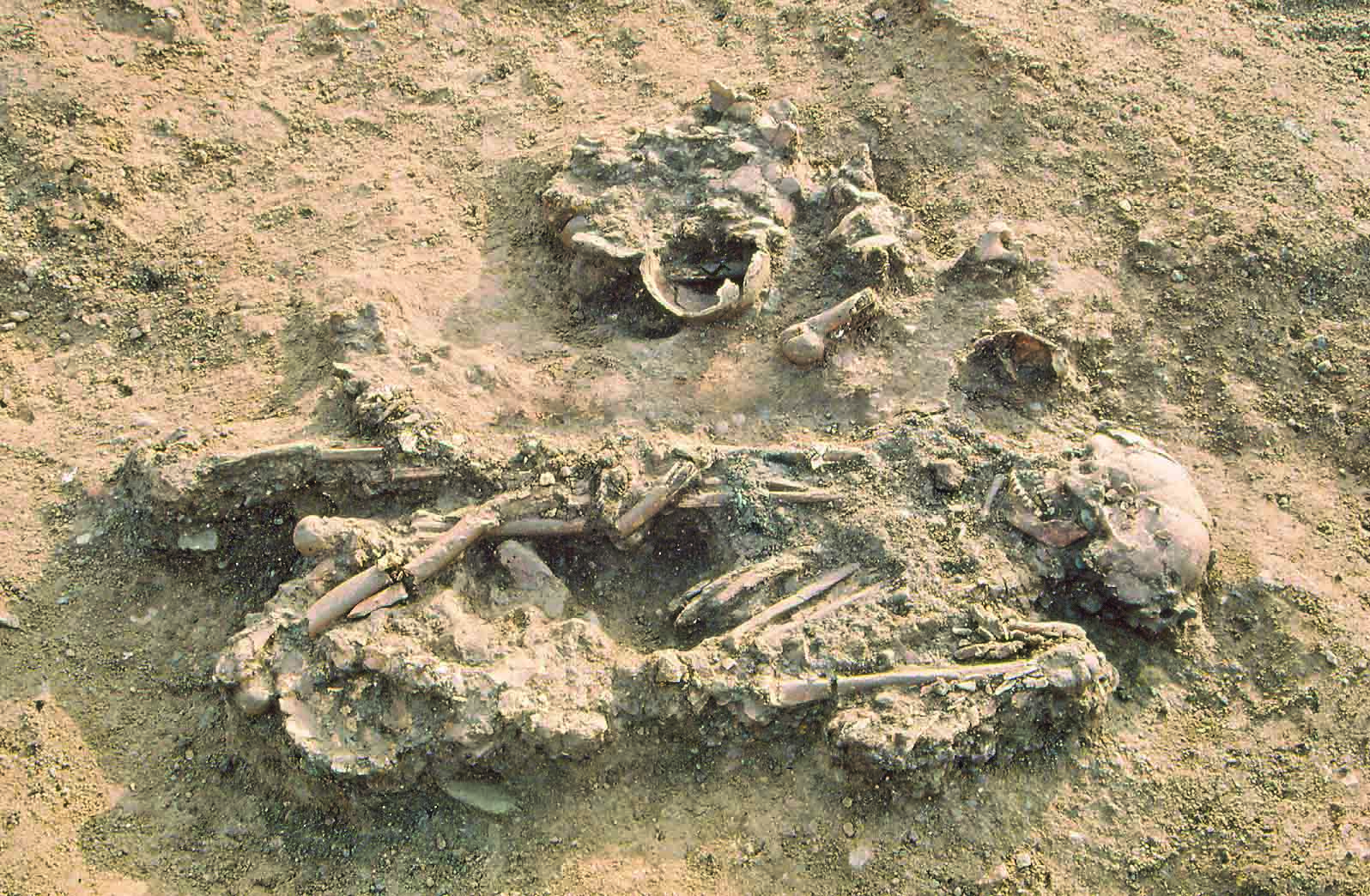

Bronze Age Britons seem to have collected and kept as relics the bones of people they’d lost. The macabre keepsakes included skulls and long bones as well as bits of cremated bones. Archaeologists Thomas Booth of the Francis Crick Institute and Joanna Brück of University College Dublin radiocarbon dated some of these relics that were found in settlements or in graves, where they had been intentionally placed along with skeletons buried between 4,500 and 2,600 years ago. By comparing the age of the bone relics with that of the skeletons in the associated burials or other dateable organic material, the researchers determined that the redeposited bones belonged to individuals who had lived within memory of the deceased. “The retention of human remains was a very broad practice and it encompassed lots of different kinds of relationships,” says Booth. “This included family members and social kin, but also enemies and people who had particular skills one wanted to take advantage of.” Some skulls were damaged after death, he says, perhaps suggesting that they were the remains of captives, while others were perforated and may have been hung on display in homes. Still other types of bones were fashioned into useful objects. These include a human femur that was carved into a musical instrument and buried with a man, tying him to the previously deceased individual’s identity, occupation, or deeds in life.