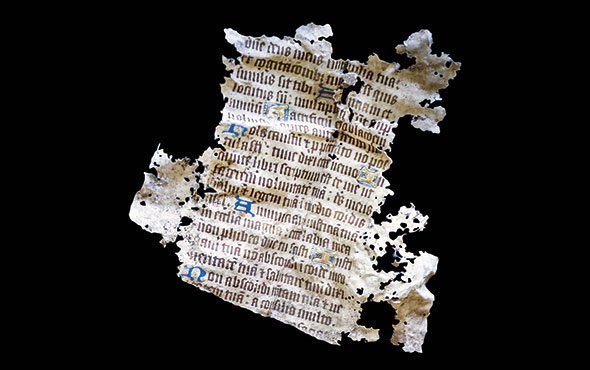

Two pipes unearthed at Indigenous sites in central and southeastern Washington—one dating to before contact with Europeans, and the other used after their arrival in the 1700s—have revealed the changing smoking habits of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Washington State University pioneered a process called ancient residue metabolomics, which has allowed them to extract multiple compounds from the pipes’ surfaces and interiors and to identify plants used for smoking.

In the precontact pipe, they detected the presence of smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), which smokers likely added to tobacco to improve its flavor and to take advantage of the plant’s medicinal properties. This pipe, which was made of stone, also contains traces of Nicotiana quadrivalvis, a species of tobacco that was once cultivated locally by Native tribes. The post-contact pipe, which was made of clay and discarded in the late eighteenth century, is of a type introduced by Europeans and quickly adopted by Native Americans. The pipe contains Nicotiana rustica, a more potent tobacco species of South American origin that was grown by tribes in the eastern United States. Its presence in the pipe helps establish that it was co-opted by Europeans for use in their trade tobacco. “The presence of rustica in the post-contact pipe confirms that indigenous tobacco was an important trade commodity after contact,” says Washington State University archaeologist Shannon Tushingham. This suggests that smoke plants cultivated by Native people continued to be used alongside tobacco domesticated by Europeans .