For most of the seventeenth century, China was in an almost constant state of political upheaval. After nearly 300 years of rule, the Ming Dynasty was collapsing under the weight of widespread corruption, domestic rebellion, and foreign invasions. This turmoil was exacerbated by a series of droughts and famines that swept through the land. A semi-nomadic people from northeastern Asia known as the Manchus first invaded China in 1618 and eventually established the Qing Dynasty, which would go on to rule China until 1912. But before the Qing leaders solidified their control over the country in the 1680s, China was riven not just by conflicts between the Qing forces and the Ming armies, but by peasant rebellions led by self-proclaimed kings. These events are described in the Qing-era work The History of Ming, which relied on Ming Dynasty annals compiled by court historians after the death of each emperor. Unofficial accounts left by Ming-era Chinese scholars also describe the country’s descent into chaos.

In the southwestern province of Sichuan, one of the most notorious peasant rebel leaders, Zhang Xianzhong, established a short-lived state in 1644. He called it the Daxi, or Western, Kingdom, and later that year proclaimed it to be an empire. He soon found his realm under constant threat from Ming armies in the south and Qing forces quickly advancing from the north. Zhang was running out of food to feed his soldiers, and he decided to abandon his capital city of Chengdu in the summer of 1646. Before he evacuated his forces from the city by way of the Jin River, Zhang ordered his men to load boats with gold, silver, and other treasure he had accumulated after years of plundering his enemies’ lands.

According to folklore, on a scorching day in July, Zhang’s fleet, carrying 100,000 troops, reached the town of Jiangkou, where the Jin and Min Rivers meet, when they heard drums and horns from the banks. Suddenly, arrows and cannonballs rained down on Zhang’s armada. The fleet had been ambushed by an army led by Yang Zhan, the most prominent Ming general of the time. As Zhang’s forces scrambled to fight back, they were attacked by fireships, watercraft filled with flammable material, in this case sulfur. The wind was strong, and some of Zhang’s boats were immediately engulfed in flames. The rest of his armada tried to escape, but the river was too densely packed with ships belonging to both sides. Zhang’s troops trampled each other and many fell into the water and drowned. Most of his soldiers died in the battle—and his wealth sank to the bottom of the Min River.

Zhang’s fortune, which allegedly added up to the mythical amount of one hundred million silver taels—allegedly more than the value of the entire Ming royal treasury at the time—was not forgotten. From Qing officials to local fishers, generations of treasure-seekers hunted for Zhang’s lost riches at various points along the Min River, but their exact location remained unknown. A popular local riddle went “Where the stone dragon faces the stone tiger, there are millions of silver pieces. If someone could break into it, they could buy Chengdu.” Historical accounts suggest at least six possible locations for the treasure. But archaeologist Yuniu Li of Sichuan University says that the waters near Jiangkou were the only one where gold and silver objects had ever been located.

Since 2016, archaeologists from the Sichuan Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics and Sichuan University have been carrying out extensive excavations in the Min River where it flows by Jiangkou. The researchers commissioned a series of dams, which allowed them to drain water from carefully selected areas of the river during the dry season. After removing sand and pebbles, they examined around 250 acres of riverbed. The team paid careful attention to deep grooves known as bedrock chutes, where they discovered that many objects lost during the battle had been trapped. By May 2023, they had retrieved more than 76,000 artifacts, most of which were fashioned from precious metals.

Although archaeologists found no remains of ships and few weapons directly related to the battle, the tens of thousands of other artifacts they recovered help to tell the story of Zhang’s rebellion. “These finds not only verified historical records about the Jiangkou battle and the sunken treasure,” says team leader Zhiyan Liu of the Sichuan Provincial Institute, “but also shed light on the extensive social turmoil at a time of dynasty change, as well as on Zhang Xianzhong himself as a controversial historical figure.” Ever since he first rose to power in his home province of Shaanxi by marshaling an army of desperate peasants, Zhang has been depicted in historical accounts as both a master tactician and an unthinkably cruel monster responsible for the deaths of millions of innocent people. “Zhang was smart and competent as a military leader,” says University of Southern Mississippi historian Kenneth Swope, “but he was also notorious for his unbalanced mind.” By studying the objects Zhang lost during the Battle of Jiangkou, archaeologists can now chart the rise and fall of this infamous figure. They can also explore how he ruled the short-lived Daxi Empire while China’s established social and political order disintegrated and the country began its transition into a new age.

The Ming Dynasty was founded by Zhu Yuanzhang (reigned 1368–1398), a cowherd from a poor family in eastern China’s Anhui Province who went on to lead a peasant uprising that toppled the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). During the Ming Dynasty, China experienced unprecedented economic expansion. Both the Forbidden City and the Great Wall as it exists today were built during this time.

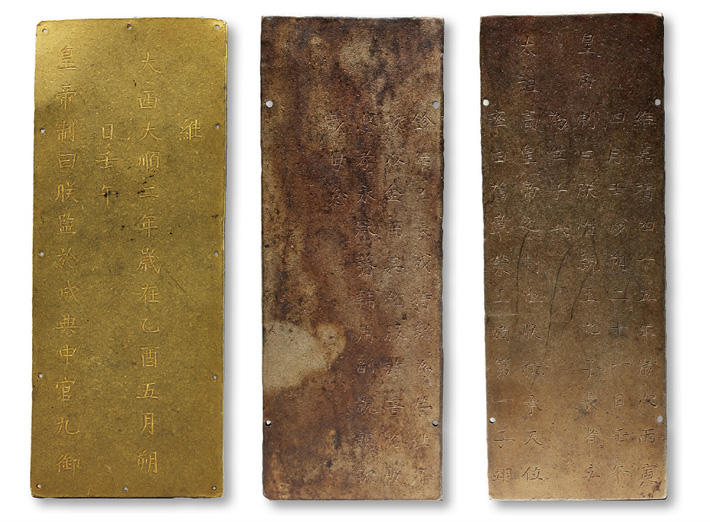

Zhu adopted an established bureaucratic process known as the enfeoffment system in order to assign fiefs to his sons. He and later Ming emperors officially bestowed titles and lands upon relatives by gifting them inscribed gold plaques known as conferring tablets. The Ming imperial clan expanded to such an extent that supporting its members imposed a severe burden on the peasantry. During the late Ming period, Qing histories record, heavy taxes, corrupt government officials, and natural disasters pushed many people into extreme poverty and led to widespread starvation and even cannibalism.

In Shaanxi Province, where the situation was especially dire, some peasants refused to pay taxes and began to form roving gangs, leading to clashes with Ming forces. Among these rebels was Zhang Xianzhong, who is described in some chronicles as a tall, ruthless young man from the city of Yan’an who had served in the Ming army before deserting to join the peasant rebels in the 1630s. “Zhang is said to have had sharp eyes, a big beard, and a thunderous voice,” says Swope. Known as the Yellow Tiger, he was famed for his skill as an archer and was well versed in military tactics. Zhang used his natural aptitude as a soldier to quickly assemble an army from a ragtag group of bandits. His reputation as a military commander soon attracted some 10,000 followers to his banner. Zhang’s early career as a rebel leader is said to have been marked by acts of kindness, such as ordering his personal physician to attend to children and redistributing money his army took from imperial palaces to local people.

Zhang’s army fought its way from Shaanxi across southern China as far east as Anhui, the Ming Dynasty’s home province, where it destroyed the dynasty’s ancestral temple. In more than two dozen cities, his soldiers defeated army after army and plundered the riches of royal families, regional governments, and wealthy civilians. Most of the artifacts recovered from the Jiangkou battlefield, including gold seals, hundreds of silver ingots, and numerous smaller objects such as earrings and hair pins, had been carried off by Zhang’s soldiers during a decade of campaigning across China. They serve as a map of sorts to his military exploits. “The items unearthed from the Jiangkou battleground site match well with Zhang’s route of conquest as recorded in the literature,” Liu says.

One typical silver ingot, weighing four pounds, was apparently pillaged from the palace of a Ming vassal known as the king of Chu in the city of Wuchang after Zhang seized it in 1643. Inscriptions on the ingot say that it was produced by an artisan named Zeng Guan in 1610 and given to the king as part of an annual tribute. Its upper edges were unevenly bent, which means that, like many other ingots found at Jiangkou, this one had been folded by Zhang’s soldiers to save space on the boats they used to evacuate Chengdu. In 1643, Zhang’s army also occupied the city of Changde and seized, among other objects, a pair of gold conferring tablets from the palace of the king of Rong, another Ming vassal. Inscriptions on the tablets, which each weigh a little more than three pounds, describe a major event for the royal family. In 1566, the Ming emperor Jiajing (reigned 1521–1567) officially conferred the title of crown prince of Rong on Zhu Yizhen, who would become king after his father died three decades later. The inscriptions credit Zhu Yuanzhang, the Ming Dynasty’s first emperor, with establishing the enfeoffment system. They also instruct crown princes to study classic books and remain loyal to and always defend the central government. “Enfeoffment was a major component of the Ming Dynasty’s political system,” Li says. As Zhu Yuanzhang doled out fiefs to his 26 sons, conferring tablets were seen as a symbol of identity for vassal kings and their offspring. Much like British royalty today, Li explains, the vassal kings of the Ming Dynasty carried no real administrative responsibilities and relied on taxpayer money.

Analysis of the conferring tablets recovered from Jiangkou shows that they contained only 48 percent gold, significantly lower than Ming laws stipulated. “Gold conferring tablets were required to be made with 100 percent pure gold in the early Ming period,” says Li. “Apparently, the Ming government was going through increasing financial difficulties during its late years.”

In 1644, backed by an army that now counted half a million soldiers, Zhang turned his attention to Sichuan Province, a fertile region bordering Shaanxi, known throughout Chinese history as “heaven’s storehouse.” He now had a different goal—to transform himself from leader of a marauding peasant army to founder of his own royal dynasty. Within a year, Zhang defeated most of the Ming armies in Sichuan and took over Chengdu, formerly the regional capital of the Ming vassal king of Shu. There, he established the Daxi Kingdom and, shortly after, declared himself emperor.

When Zhang’s soldiers broke into the king of Shu’s residence, they found what was likely their largest and most valuable trophy yet—a 200-year-old gold seal that weighed more than 17 pounds and had been used by 13 generations of Shu crown princes. During excavations at Jiangkou, archaeologists found the seal in pieces. It’s likely that after taking the prized object, Zhang’s rebels deliberately broke it, symbolically marking a shift in power and the dawn of a new authority.

While Zhang’s treasury mostly contained artifacts from the coffers of Ming Dynasty rulers and their subjects, researchers also found a number of gold and silver objects that were made and used during his reign as the emperor of Daxi. For example, a gold tablet recovered from Jiangkou includes inscriptions reporting that Zhang conferred titles on his concubines following traditional rituals on a certain day in 1645. The team also found gold and silver commemorative coins that Zhang minted to honor meritorious soldiers in his army. The coins, of which only one example was previously known, measure about two inches across and are engraved with four characters indicating that they were awarded for service to the emperor of Daxi. The coins are not worn down, suggesting they were not circulated as currency and were likely kept as prized possessions by the soldiers they were originally awarded to. A number of silver ingots found at Jiangkou bear inscriptions suggesting they were minted specifically for Zhang’s subjects to fulfill their tax obligations. Peasant leaders with just a few battlefield victories could claim the title of king relatively easily without establishing a functioning government or putting in place a strategic military or political vision. “Little was known about the Daxi Empire, and there were even controversies about whether Zhang ever really became an emperor or simply proclaimed himself a king,” says Liu. “With these artifacts, we can confidently say that he did establish a government. The fact that he adopted the same conferring systems and silver ingots for taxation purposes seems to suggest he was running his kingdom in a way very similar to that of the Ming rulers.”

Another important artifact from Jiangkou belonged to Zhang himself. This seven-pound gold seal with a tiger-shaped knob was cast and given to him by his main rival, Li Zicheng, in November 1643. Li, who led a major rebellion in Shaanxi around the same time as Zhang, was about to declare himself emperor. Inscriptions on the seal suggest he wanted to offer amnesty to Zhang. “The tiger seal implied a political agreement between Li and Zhang,” says Liu. The inscriptions on the seal say that Li promised to save high positions for Zhang and Zhang’s subordinates in his government in exchange for his fealty. However, Zhang likely already planned to occupy Sichuan and establish his own kingdom there. He took the seal, but never subordinated himself to Li’s rule. “The two were frenemies,” says Liu. “They shared a goal of overturning the Ming Dynasty, but as rivals they never liked each other—and maybe always wanted to kill each other.” Zhang’s rival did manage to seize Beijing in 1644 and dethrone the last Ming emperor, Zhu Youjian (reigned 1627–1644). Li established his own dynasty in the Chinese capital, but his reign lasted only 42 days. Qing armies forced him to flee the city, and his eventual fate is murky, though some accounts describe his death at the hands of villagers in Hubei Province.

In Sichuan, Zhang faced both internal and external unrest. He increasingly lost patience with the restive local population and began to execute those who resisted his rule, a policy that soon led to wholesale massacre of the province’s residents. The History of Ming and memoirs of Jesuit missionaries who were living in Chengdu at the time say that Zhang ordered the deaths of millions of people from Sichuan, including women, scholars, monks, and even soldiers who had fought for him. He was said to have been a terrifying killer who would flay or roast people alive. Zhang encouraged his men to chop off victims’ body parts and then promoted them based on the number of hands, feet, or genitals they turned in.

Following his resounding defeat at Jiangkou in 1646, Zhang was forced to return to Chengdu, where he carried out another round of massacres of the local population. His troops set the city on fire before fleeing northward, leaving nothing but a smoking ruin. It would take decades for the people of Chengdu to recover from this devastation. In 1647, one of Zhang’s generals deserted to the Qing side because of long-festering resentment of Zhang’s bloody rule. As one account has it, the disaffected general pointed Zhang out to Qing archers when the two armies were arrayed across a river from each other. Zhang was struck in the stomach by an arrow and fell dead from his horse.

Liu and other scholars believe that Zhang probably ruled his realm relatively efficiently in his early days as an emperor—before he turned to mass slaughter as a political tool. “There is no doubt that Zhang killed many people in Chengdu,” he says. “However, it would be unfair to blame the region’s devastation on him alone.” During the transition from the Ming to Qing periods, Sichuan’s population is estimated to have dropped by 90 percent. Many of the deaths were likely caused by a decades-long famine and by wars that continued after Zhang was killed, and are not attributable to his short-lived reign.

Without Zhang as their leader, his soldiers joined the Ming armies. They fought against Qing forces for more than a decade in the southern province of Yunnan. The Qing Dynasty completed its conquest of China in the early 1680s, finally bringing an end to the chaos that had sparked the peasant rebellions and enabled the rise of rulers such as Zhang.