The sun illuminated the stadium in Ephesus, a wealthy harbor city in western Anatolia, on a day of eagerly anticipated gladiatorial combat. Festive decorations adorned the arena, and the air was filled with the scent of refreshing perfumed water sprayed over the crowd. As the gladiators were announced, they paraded before the spectators to the strains of music, displaying their powerful physiques and their readiness to fight. All eyes were drawn to two combatants in particular: Margarites, known as the “Pearl of the Arena,” and Palumbos, whose stage name was the “Male Dove.” By the time the sun was high overhead, the arena was packed to capacity. A horn signaled the start of the afternoon’s games.

A pair of mounted gladiators featured in the initial spectacle, but the highlight was the duel between Margarites and Palumbos. Margarites, clad only in a small loincloth secured by a wide belt, wielded a net and trident—classic armaments of his type of gladiator, the retiarius, whose light weapons facilitated speed and agility. Palumbos was a formidable murmillo, whose large helmet, wooden shield, and gladius—the style of short sword that lent the profession its name—augmented his imposing stance. As the combat began, Margarites deftly cast his net toward Palumbos, attempting to ensnare him. Palumbos, despite the weight of his armor and shield, skillfully eluded the gambit. Margarites circled the arena searching for an opening, while Palumbos remained patient. The contrast between the retiarius’ speed and the murmillo’s endurance became evident. As time passed, fatigue began to weigh on Margarites. In a final effort, he launched his net once more, but Palumbos evaded him again and countered with a swift sword strike. Recognizing impending defeat, Margarites dropped his weapons, signaling surrender.

The expectant crowd awaited a verdict. Some cried “Iugula!” (Cut his throat!), while others yelled “Missus!” (Reprieved!). Margarites’ dignified composure swayed the games’ patron, who indicated the gladiator’s life should be spared. As the victorious Palumbos departed, Margarites, too, left the arena with the spectators’ respect. Both men would live to fight another day, and this battle would be remembered for years to come.

Gladiatorial games are believed to find their origins in the burial rituals of the Etruscans, who inhabited the Italian peninsula from about the eighth to third century b.c. Frescoes in tombs dating to the fourth century b.c. in the regions of Lucania and Campania in southern Italy depict funeral games held to honor fallen warriors in which captured enemies were forced to fight. Since the beginning, then, these contests were as much ritual as spectacle.

The first recorded gladiatorial contest in Rome took place in 264 b.c. Following the death of the consul Junius Brutus Pera, his sons organized a public event as part of their father’s funeral rites that included clashes between three pairs of gladiators. These games, held in the Forum Boarium, Rome’s ancient cattle market, enhanced the family’s social standing. The first-century a.d. historian Plutarch tells of games held by Julius Caesar in 65 b.c. Over time, the total number of gladiators participating in funeral games increased, and the events became a showpiece for entertaining the populace, honoring the emperor, and forging political careers. Though unquestionably brutal, gladiatorial combat signified the triumph of courage over death for the Romans. “The most common perception of gladiatorial games is that they were violent and gruesome because someone always died,” says archaeologist R. R. R. Smith of the University of Oxford, who directs excavations at the site of Aphrodisias. “This isn’t true. In gladiatorial games, most of the time, both participants left the arena on their feet. The games weren’t about killing, but about the excitement of two men fighting, about showcasing skill, discipline, endurance, strength, tactics, and different weapons.” In the rare cases when gladiators were killed or condemned to death, they had been trained to die theatrically to add to the performance’s impact.

Anatolia’s transition from being ruled by a succession of local empires to becoming part of the Roman world at the start of the second century b.c. involved military conquests, diplomatic maneuvers, and cultural assimilation. Festivals held in honor of Roman emperors, many of which included gladiatorial contests, were key events in this process of Romanization. Anatolia played a significant role in the development and expansion of gladiatorial culture, and the games became a way in which the vast region reinforced its allegiance to Rome.

Ephesus was one of the first Anatolian cities to host gladiatorial games. This important trading hub came under Roman control in 133 b.c. after Attalus III of Pergamon (reigned 138–133 b.c.) bequeathed his kingdom to Rome. Ancient sources indicate that gladiatorial games in Ephesus were organized by the Roman general and statesman Lucius Licinius Lucullus. “While there’s no epigraphic evidence, literary sources do refer to gladiatorial games organized and supported by Lucullus in Ephesus,” says archaeologist Martin Steskal of the Austrian Archaeological Institute. “These are the earliest mentions of gladiatorial games in the city.”

These Roman-style games quickly captured people’s attention. By the late first century a.d., their popularity had spread throughout Anatolia, from the region of Pamphylia in the south to Bithynia in the north, though many people may have been unaware of their roots in sacred religious rites. “It’s an interesting question how distant this cultural practice was for the audience in Anatolia,” says Smith. The games were, however, almost certainly seen as a way to demonstrate locals’ adoption of Roman ways. Adding to the ample literary evidence exploring the world of gladiators, over the last century archaeologists have uncovered figurines, graffiti, friezes, and especially grave stelas depicting gladiators throughout Anatolia. It seems that aristocrats not only from Ephesus but also from cities such as Aphrodisias, Hierapolis, Aydın, Stratonicea, and Cibyra began hosting the lavish spectacles they had witnessed in Rome.

Most of these cities already had theaters and stadiums to hold Greek-style athletic contests including wrestling, boxing, the long jump, and discus and javelin throwing. With some modifications, these venues were suitable for gladiatorial contests as well. “Theaters were seen as places where gladiatorial games could coexist harmoniously with other cultural activities,” says Smith. Wealthy aristocrats and religious officials soon realized that sponsoring games was a faster and more effective way to curry public favor, and thereby amass political power, than, for example, building bathhouses or aqueducts. But it was also expensive. Arranging gladiatorial shows, whether by renting combatants from a lanista—a gladiator school owner—contracting with freelance gladiators, or purchasing an entire gladiatorial family, was very costly. An inscription dating to a.d. 177, for example, records that the price to hire professional gladiators, who were graded according to their skill and experience, was substantial, ranging from 3,000 to 15,000 sesterces. A letter from the emperor Hadrian (reigned a.d. 117–138) to the city of Aphrodisias, inscribed on a slab that was later reused as a paving stone, suggests that high priests, who were required to stage gladiatorial games as part of their official duties, found this an intolerable financial burden. “It’s possible to read the inscription as evidence that, as an incentive to stand for office, potential candidates were permitted to contribute to the construction of an aqueduct instead of the staging of a gladiatorial show, thereby replacing fleeting entertainment with a lasting improvement to the civic infrastructure,” says classicist Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University.

Despite the hefty financial outlay, gladiatorial games attracted a great deal of public interest and were a boon for tourism, with spectators traveling from across the region to watch, purchasing figurines or oil lamps depicting their favorite fighter, and dining and staying in the city.

Behind a day in the arena was a well-organized professional system. “We know that there were schools where gladiators were coached by experienced trainers and that they were well fed and received medical care,” Steskal says. Sources indicate that gladiator schools even had specialized doctors on call. The physician Galen, who lived in the Anatolian city of Pergamon in the mid-second century a.d., writes that no gladiators died over a five-year period when he provided them with medical care. “Galen likely learned about medicine from, among others, his predecessor, the Ephesian physician Rufus,” says Steskal. “The last thing a school owner wanted was for his gladiator to die. If a gladiator died in his first fight, it would mean all that investment was wasted.”

A common misconception is that all gladiators were slaves forced to fight and die in the arena. “The majority of gladiators across the empire were indeed slaves who were selected and trained,” says archaeologist Şükrü Özüdoğru of Mehmet Akif Ersoy University. Yet, during his excavations in Cibyra, Özüdoğru hasn’t found any direct evidence of enslavement. “There’s no data showing that this person was a slave of this person, bought or sold at a certain price, or that they originated from a specific background,” he says. Özüdoğru adds that there is also no direct evidence of enslavement of gladiators in other cities across Anatolia. “This suggests a more humanistic approach than we see elsewhere,” he says.

Many gladiators—including slaves, former soldiers, and once-enslaved fighters who returned to the games voluntarily—endured long years of combat before being granted their freedom. “Although gladiators were legally regarded as slaves, they were often revered as popular and admired figures,” Steskal says. “Some men, seeking to pay off debts or amass wealth, voluntarily chose the gladiator’s path. In doing so, they faced the peril of forfeiting all legal rights. But, if victorious, they could secure both wealth and the opportunity to live a liberated life.”

Like the Roman Colosseum, the arenas of ancient Anatolia were not solely venues for gladiatorial combat but also hosted animal hunts called venationes. These events began early in the day and could involve hunting a wild boar or bear to showcase participants’ courage and skill and to symbolize the removal of local predators that posed a threat. Some animals were imported from far-off lands, a particularly pricey proposition. Fights involving such wild animals underscored the munificence of the games’ sponsors. Pitting men against exotic beasts from Africa was a testament to their largesse and was intended to broadcast a level of control over the empire beyond the arena. “Gladiators weren’t merely instruments of entertainment, but also complex reflections of social structure, political power, and local identity,” says Smith. “They served as heroes in the eyes of the public while playing a crucial role in a complex social hierarchy.”

After the venationes, at midday, common criminals and political prisoners were executed by crucifixion or mauling by wild animals. This part of the games, too, had a social function, symbolizing the restoration of legal order.

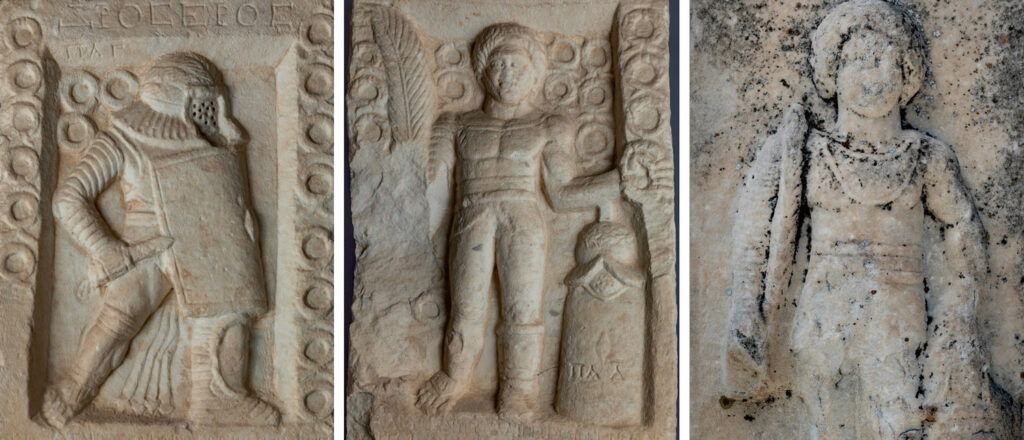

One of the main sources of information about Roman gladiators are grave stelas that have been unearthed across the provinces of Anatolia. Between 1991 and 1995, archaeologists with the Austrian Archaeological Institute working under its then-director Dieter Knibbe excavated along the sacred processional way to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus—one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. There, they uncovered a third-century a.d. stela that reads: “Hymnis had this tomb made for Palumbos, in memory of her own husband.” The image on the stela clearly depicts Palumbos as a murmillo. Although the relatively simple stela isn’t a sign of great wealth, it is evidence that Palumbos and his wife could afford a proper commemoration after his death and have it placed in a prominent location in the city.

Another stela found in Ephesus was commissioned by the retiarius Margarites and a fellow gladiator named Peritina. It bears the inscription: “Peritina and Margarites in memory of the retiarius Euxeinus.” And a relief discovered amid the stone rubble between the stelas commemorating Palumbos and Euxeinus bears a two-line inscription at the bottom that reads: “From Tyche to her husband, whom she loved above all else.” These two reliefs are so alike in quality, shape, and style of lettering that archaeologists believe they were crafted by the same artist.

Grave stelas belonging to gladiators have been unearthed in other Anatolian cities as well. A stela from Hierapolis, commissioned by a woman named Marcellina for her first-class gladiator husband, Nikephoros, meaning “Bearer of Victory,” depicts the fighter holding a palm branch. An inscription on a grave stela belonging to the murmillo Droseros found in Stratonicea reads: “The man who killed me was once on the stage but now in the arena as Achilles, brought down by the games of Fate herself, Moira.” To mark his victories, Droseros was honored with 17 wreaths, which are shown on the stela. His fellow townsman, the plurimarum palmarum, or winner of many victories, Polydeukes, also known by his stage name, Vitalius, was commemorated with 15 wreaths and a palm branch, symbolizing his victories. His epitaph reads: “Here lies Vitalius, a brave man in boxing; Polydeukes, strong and true to his name, skilled in boxing, slain in the arena by his own hand.”

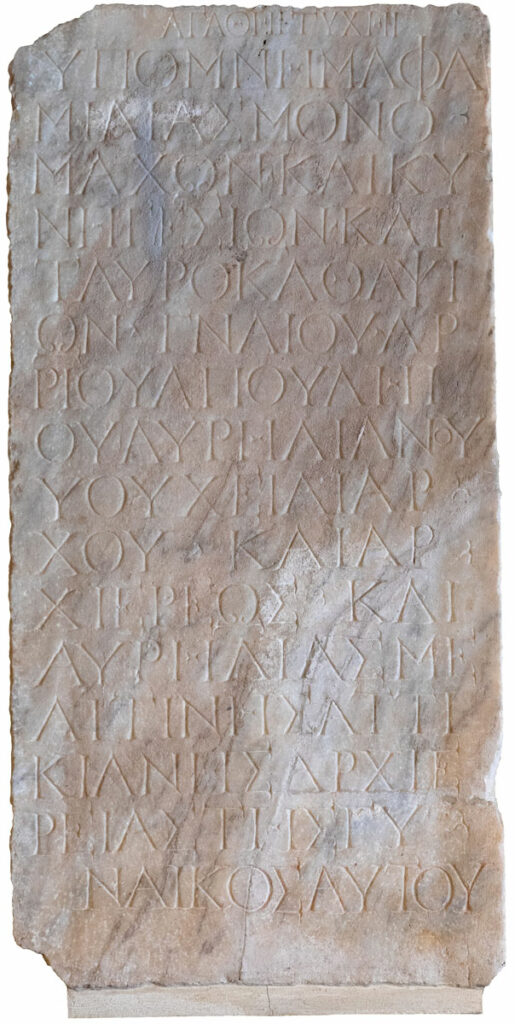

Along with the private memorials to gladiators’ lives carved on grave stelas, public inscriptions and artwork provide additional information about both the fighters and the families that sponsored them. For example, a marble inscription erected in the agora of Ephesus in the third century a.d. names one of the Ephesian families who displayed a keen interest in sponsoring gladiatorial games. The inscription is dedicated to Marcus Aurelius Daphnos, who is described as an asiarch, a civil or priestly official who oversaw both religious rites and public games. His affiliation with a gladiator fan club called the Philoploi Philovedioi, or weapon-loving supporters of the Vedii family, is also mentioned. The Vedii family were the wealthiest citizens of Ephesus in the second and third centuries a.d.—and may have sponsored the games in which Palumbos performed. The inscription reads:

He was thrice asiarch of the temples in Ephesus, who held a munus (“games”) in his fatherland with thirty-nine pairs [of gladiators] fighting sharply for thirteen days, and who killed Libyan beasts, and who was favored by the emperors and wore at the front of the procession the golden crown as well as the purple robe. Those in this place who follow the Vedii, who love arms, honor him as their own euergetes (“benefactor”).

Associations of fans similar to the Philoploi Philovedioi are also known to have existed in the city of Miletus on the western coast of Anatolia, as well as in Hierapolis, where archaeologists have uncovered inscriptions relating to gladiatorial contests, including one that mentions a gladiator fan club known as the Friends of Arms. In the early third century a.d., Hierapolis became a neokoros, a provincial city that was the custodian of a temple dedicated to the imperial cult. At this time, explains Grazia Semeraro, an archaeologist at the University of Salento and director of the Hierapolis Archaeological Mission, the status of the high priest who was responsible for staging games was increasing and the importance of gladiatorial games was growing. Evidence of these developments has been found on the city’s public monuments. Images of venationes on buildings such as the theater and the stoa-basilica attest to the social, cultural, and political significance of these spectacles. On a monument commemorating an event held in the amphitheater, an inscription expresses thanks to the patrons:

With good fortune. In memory of the gladiators’ familia and hunting shows, including the taurokathapsia (“bullfight”) organized by Gnaeus Arrius Apouleios, and son of Aurelianos, legio tribune and high priest, along with his wife, the high priestess Aurelia Melitine Attikiane.

Two inscriptions from Hierapolis provide evidence of how gladiatorial contests were supervised. Gladiators were not, in fact, engaged in the chaotic, savage massacre of many people’s imagination. On the contrary, the games were governed by detailed sets of rules and overseen by arbiters, or referees. These inscriptions, dedicated to local arbiters named Apollonios Menandros and Zosimos, describe the men as secunda rudes, or second umpires. If the city provided gladiators and referees for the games, it’s possible there was a permanent gladiatorial organization in Hierapolis. This interpretation is supported by a grave stela found at the end of the nineteenth century in the village of Karahayıt, three miles north of Hierapolis. The artifact, which was described at the time but is now lost, was dedicated to a therotrophos, or animal trainer, who was responsible for maintaining the wild beasts used in hunts.

An impressive set of reliefs from Cibyra—the most extensive collection of gladiator friezes from antiquity—provides some of the best evidence of how gladiatorial combat was conducted across different regions of the Roman Empire. The majority were discovered during rescue excavations in 2001 and 2002. In 2011, additional blocks thought to belong to the same series of friezes were unearthed on a road running alongside a necropolis and in the foundation of a house in the nearby town of Gölhisar. The friezes were created between a.d. 150 and 200 and depict venationes and battles between gladiators. They may once have adorned the eastern parapets of the city’s stadium. According to Özüdoğru, the period when gladiatorial games were most popular coincided with the city’s peak in wealth, population, and commercial activity. He adds that the vivid details of the reliefs—down to the depiction of the uneven paving stones of the stadium, which archaeologists have unearthed—suggest that the artists observed these contests in person.

For centuries, in addition to serving vital social and political functions, gladiatorial contests were the preeminent form of entertainment for the Roman populace. From the third century a.d. onward, however, due to an economic crisis and rampant inflation, the number of wealthy sponsors dropped, the games’ popularity began to fade, and the profession lost some of its allure.

By the fourth century a.d., the spread of Christianity—which condemned both the violence of the games and their roots in pagan rituals—further contributed to the games’ decline. Venationes became even more popular at this time, as they were perceived as a more humane alternative. Although tangible symbols of the empire endured—people still traveled, as they do now, on Roman roads, and Roman aqueducts still carried water, as they continue to do—the ubiquity and grandeur of thegames would never return.

Slideshow: The Gladiators Are Coming

In cities across ancient Anatolia, people enjoyed gladiatorial contests that pitted man against man and man against beast.