In his account of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon, the first-century b.c. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus describes the Hanging Garden—not Gardens—as a lush landscape whose tree-filled terraces recalled the shape of a theater. He and other Greek and Roman authors based their descriptions of this easternmost of the wonders on earlier Greek accounts that no longer exist. Many of the writers of these reports had traveled throughout Mesopotamia as part of Alexander the Great’s retinue in the fourth century b.c. and, presumably, visited the sites they chronicled. Like Diodorus, several writers identify Babylon as the Hanging Garden’s location—but only the first-century a.d. Roman historian Josephus attributes its construction to the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (reigned 604–562 b.c.). Nevertheless, the king’s name has persisted in the garden’s lore. Scholars have found no trace of the garden in Babylon’s ruins or in the copious cuneiform texts unearthed there. Furthermore, the city’s location at the edge of a desert, says Assyriologist Stephanie Dalley of the University of Oxford, would have made it an improbable site for a verdant garden. “There’s no way you could have watered a garden there from the Euphrates River,” she says, “because there are no tributaries from which you could lead enough water down.”

Dalley proposes that the Hanging Garden actually existed a century earlier than Nebuchadnezzar’s reign and believes it was located in the city of Nineveh, some 300 miles north of Babylon. Situated along the Tigris River in present-day northern Iraq, Nineveh was in a mountainous area that had a considerably wetter climate than Babylon. Around 700 b.c., the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 b.c.) made Nineveh the capital of his empire and built a sprawling palace there. Nineteenth-century archaeologists uncovered two broken stone reliefs, each depicting a tiered, forested garden in Nineveh. One relief was found in the palace of Sennacherib and the other in the palace of his grandson Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–627 b.c.). The Sennacherib panel doesn’t survive, but excavators’ original drawings of it bear striking similarities to ancient descriptions of the Hanging Garden. “This relief very clearly corresponds in several respects to details given in the Greek sources we have,” Dalley says. “The depiction of a pillared walkway and how the roofing on which the trees stand is layered is an astonishing coincidence with what Greek writers say.”

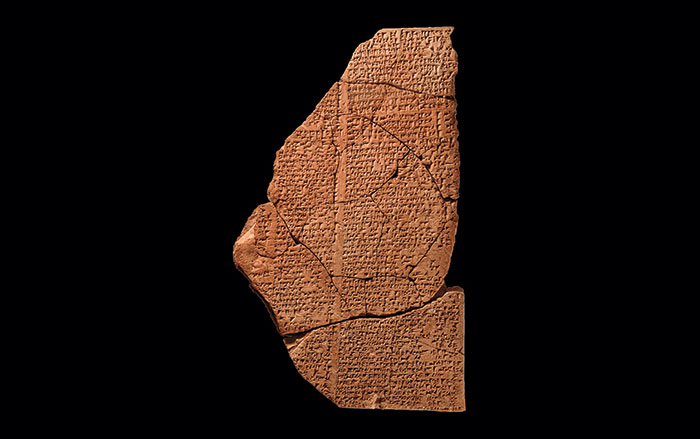

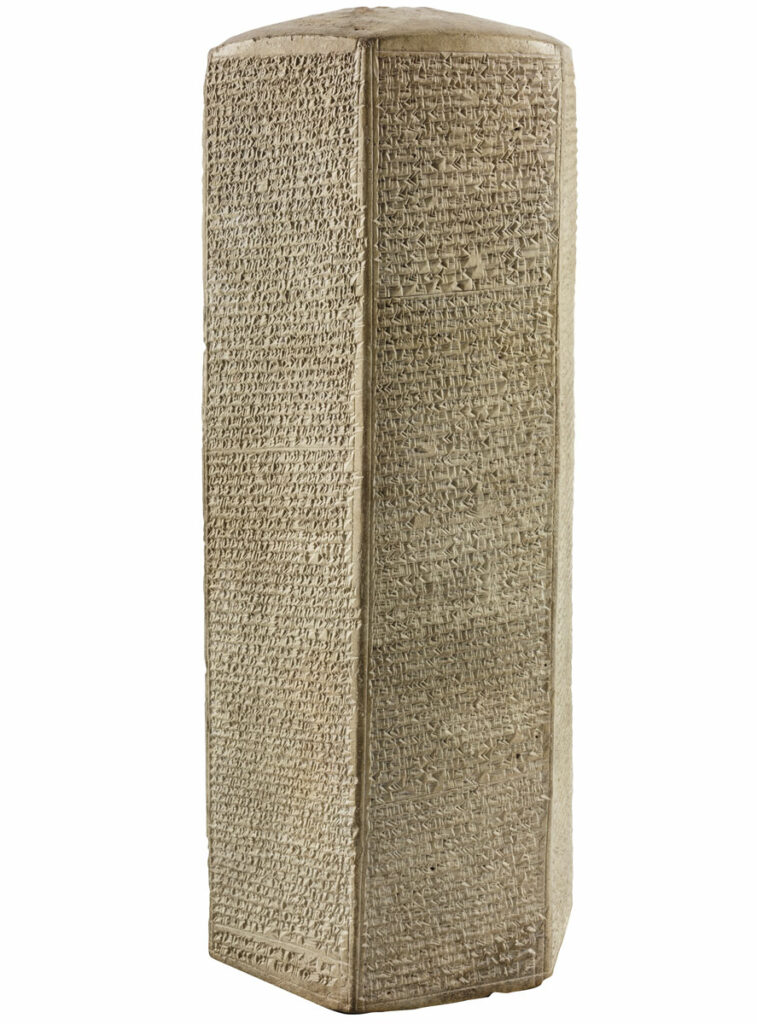

Streams and irrigation canals shown on both reliefs are also mentioned in a text commissioned by Sennacherib that records his grand efforts to transform Nineveh. This text is inscribed in cuneiform on two clay prisms. The king describes his palace garden—a park with fruit trees and aromatic plants that was built to resemble a mountainous landscape—as a monument that was “to be a wonder for all peoples.” He also mentions bronze devices used to raise water to the terraces, an engineering feat matching several later descriptions of the Hanging Garden. Archaeologists have uncovered an aqueduct and system of canals dating to Sennacherib’s reign in Nineveh’s environs. This is further evidence supporting Dalley’s argument that Nineveh may have been the elusive garden’s true location after all.