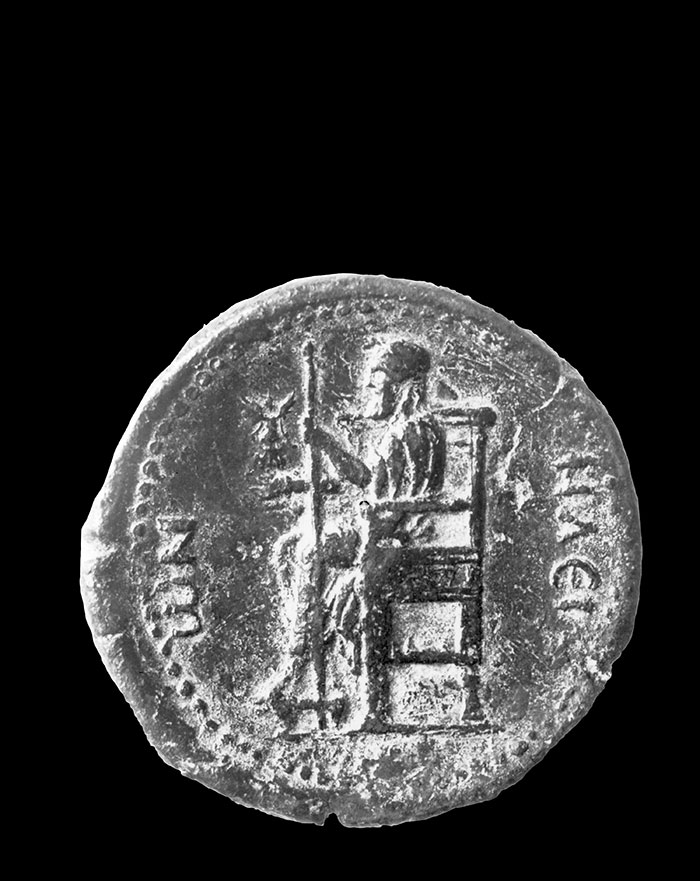

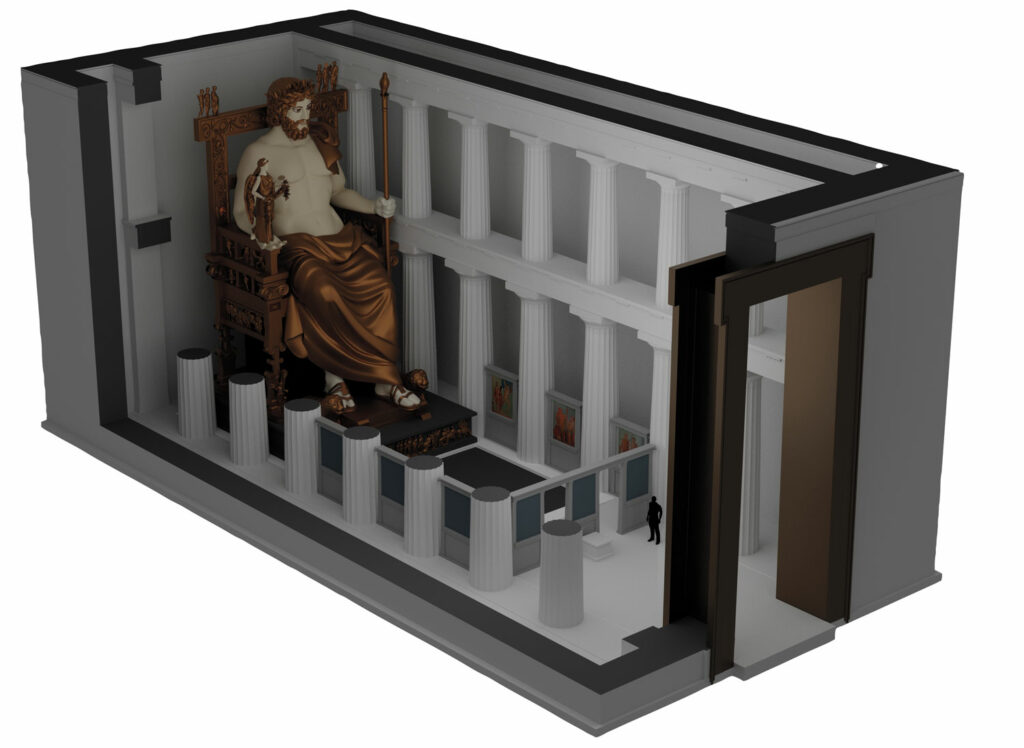

People from throughout the ancient Greek world regularly flocked to the sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia for festivals, including the eponymous Olympic Games held there every four years. The Temple of Zeus, which was built beginning around 472 b.c., was the largest sacred edifice in western Greece. Around 430 b.c., the great Athenian sculptor Phidias was commissioned to craft a monumental wooden statue of Zeus covered in ivory and gold, the size of which would exceed that of the sculpture of Athena he had designed for the Parthenon in Athens. Placed on a gilded base at the back of the temple’s cella, or main chamber, the sculpture depicted the god sitting on a throne. In his left hand, Zeus held a scepter with an eagle resting atop it, and in his right, a statue of the victory goddess Nike. At 42 feet tall, the sculpture nearly brushed up against the cella’s ceiling—giving the impression, writes the first-century b.c. Greek geographer Strabo, “that if Zeus arose and stood upright, he would unroof the temple.” Phidias’ statue remained an object of awe for 900 years, even after it was relocated in the early fifth century a.d. to a palace in Constantinople. The divine image was on display there until a fire destroyed it in a.d. 475.

To accommodate the sculpture, Phidias raised the height of the cella. He also installed a large rectangular pool filled with olive oil in front of the statue. Since the nineteenth century, archaeologists have speculated how such a cavernous space would have been illuminated and how much of Phidias’ masterpiece visitors would have been able to see. Scholars have proposed many possible solutions, including an open roof, skylights and windows, translucent marble roof tiles, and small openings in the roof tiles. However, these have little to no archaeological basis. “I don’t think Greek temples were meant to be extremely well lit,” says University of Oxford archaeologist Juan de Lara. “It’s possible that the idea of the god emerging from darkness was part of the ritual of Greek religiosity.”

De Lara has produced 3D models of the statue and cella to simulate the effects that possible lighting sources and building materials would have created, accounting for evidence that others have overlooked. For example, archaeologists have uncovered traces of parapet walls surrounding the statue base and pool that might have been as high as seven feet. These walls would have obscured worshippers’ view of at least the base and Zeus’ feet. They also could have blocked light reflecting off the pool’s surface and onto the sculpture. Even so, De Lara says, natural light from the main entrance, as well as the glow from lamps or torches, could have amply illuminated the god. “Ivory and gold are very reflective,” he says, “so even a little bit of light coming in through the door would be more than enough to really highlight the statue.”