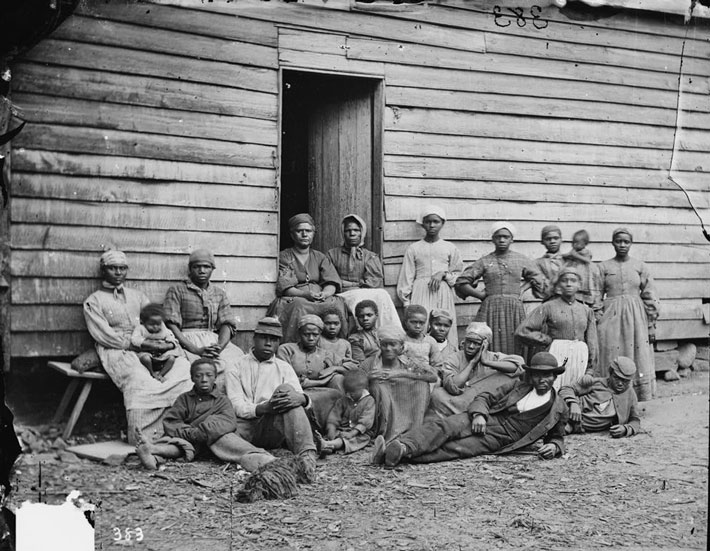

Since the earliest days of the Colonial Period, Americans of all backgrounds have distilled spirits from crops, especially grains. In the mid-nineteenth century, the imposition of taxes on alcohol and a growing temperance movement began to drive this cottage industry underground. After Prohibition began in 1920, the market for high-proof illegal alcohol, or moonshine, soared. But, says University of Nevada, Reno, archaeologist Cassandra Mills, this shadow economy is largely lost to history. “You only get records of moonshine production when people were caught and charged,” she says.

Hoping to fill in this gap, Mills has analyzed and dated the remains of more than 100 moonshine stills in Alabama using artifacts found with them. She learned that “pot stills,” aboveground stills often constructed in prehistoric rock shelters, were popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. During Prohibition, subterranean “groundhog stills” became the dominant type. She has also identified a localized tradition of “deadman stills,” low-lying contraptions shaped like coffins, which may have been constructed by a single extended family of moonshiners in northern Alabama. Mills points out that production of prohibited spirits offered an economic lifeline to impoverished rural communities, especially during the Depression. “Thirty dollars for a jug of moonshine was nothing for Al Capone,” says Mills. “But it meant everything for a family that didn’t know where next week’s groceries were going to come from.” She hopes future research into stills will show how much chemistry, craftsmanship, and ingenuity lay behind this essential, if illicit, American tradition.