Soon after Captain John Smith arrived at Jamestown in 1607, or so the story goes, he was captured by Opechancanough, the brother of the powerful Native chief Powhatan. English explorers wrote that Powhatan controlled a domain spanning much of what is now Virginia, from the state’s Piedmont region to the coast. Several tribes reportedly paid him tribute and lived within his Powhatan Confederacy. After Smith narrowly escaped execution through, he later claimed, the intervention of Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas, he set off from Jamestown to explore and chart the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Opechancanough had already taken Smith to a number of Native settlements during his captivity, including at least one on the Rappahannock River. Smith recorded that the Rappahannock peoples, who inhabited both sides of the eponymous waterway, were divided among eight communities, each with a leader, or werowance. Smith mapped or described 43 of their villages, reporting friendly encounters with some groups and hostility from others.

More than 400 years later, the Rappahannock still call Virginia home. The community numbers some 300 enrolled members, many of whom live in Indian Neck, a hamlet about 10 miles west of the modern town of Tappahannock. Since 2016, tribal members have been working with archaeologists to document their traditional homeland, a task that has presented challenges. Centuries of European encroachment and the conversion of woodland to farmland have physically separated the Rappahannock from many of their ancestral landmarks. Their towns, hunting camps, and ceremonial grounds were often built from ephemeral materials and were sometimes relocated for environmental or political reasons. Led by Chief Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Tribe and archaeologists Julia King and Scott Strickland of St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the project was launched as an initiative of the National Park Service to identify sites within a 552-square-mile swath of territory that are culturally significant to the tribe.

Using a combination of excavation, geographic information system (GIS) technology, historical research, and interviews with Rappahannock community members, the researchers have revealed a Native landscape that has long been hidden. “Smith may not have mapped the Chesapeake completely accurately,” says King. Some Native place-names are repeated on the Smith map, and some are found in multiple locations around the Chesapeake. Native settlements rarely accorded with European expectations for what a town or village should be. Still, by combining the present-day community’s knowledge with the map Smith made in 1608, satellite imagery, and environmental data from the area, the team has identified some 20 places of significance to the tribe and an approximate location for nearly all the settlements Smith labeled. Some of these are large towns whose whereabouts the tribe has, in fact, never forgotten. “I had been taking our youth back to places that our people occupied on the river to teach them about the history as part of a leadership training program,” says Richardson. “When the opportunity was presented to do archaeology to actually prove where these places were, I jumped all over that.”

Three of these larger settlements, Wecuppom, Matchopick, and Pissacoack, are recorded on the Smith map to have sat atop Fones Cliffs, a four-mile stretch of sandstone bluffs on the Rappahannock’s north bank. Smith describes coming under arrow fire near a marsh across the river from these cliffs as he and his companions made their way up the river. While excavations and surveys along a section of the cliffs that is now a federal wildlife preserve didn’t produce evidence of any of the settlements, the team did uncover artifacts that suggest the area remained home to Rappahannock people for decades after pressure from English settlers forced them to move their main settlements elsewhere. In particular, the team believes that, during excavations on a 250-acre parcel of land within the preserve, they uncovered a property described in historic deeds as home to a once-enslaved Native man named Indian Peter.

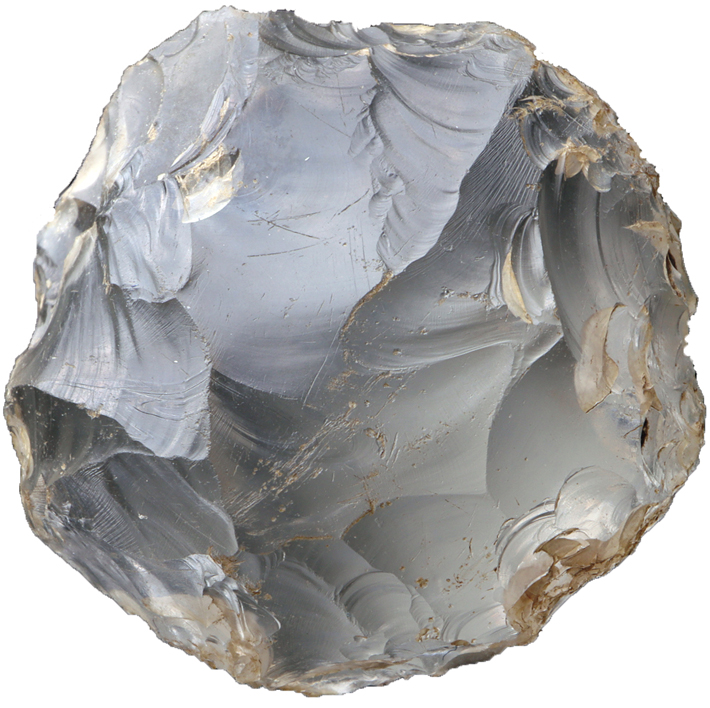

Indian Peter is recorded to have been manumitted in 1699—about 50 years after English colonists began moving into the area—and may have lived at the site between 1700 and 1730. Richardson says that some of the artifacts the team found, including worked quartz crystals and a wineglass stem carved to resemble crystal, may have been used by Peter in a medicine man–like capacity, or during cliff-top religious ceremonies that were held overlooking the river some 80 feet below. In addition to the wineglass stem, English and German ceramics, a copper buckle, tobacco pipes, a collection of nails, and other objects of European origin are evidence of the flow of goods and people up and down the Rappahannock throughout the colonial period.

King points out that Portobago Bay, some 10 miles upriver from Fones Cliffs, was the point at which the river became unnavigable for oceangoing vessels. “Portobago Bay became a natural provisioning area,” King says, “and an important place that linked the trade routes of the Atlantic with the interior.” Archival research also uncovered the identity of a Christianized member of a Rappahannock-affiliated group called the Nanzatico, who lived nearby. Edward Gunstocker, or Indian Ned, may have been so named because he was involved in smithing or trading guns. “One of the property divisions outlined in a document mentions his house,” says Strickland. Using this information, Strickland was able to approximate the structure’s location, and the team hopes to excavate the site in the future.

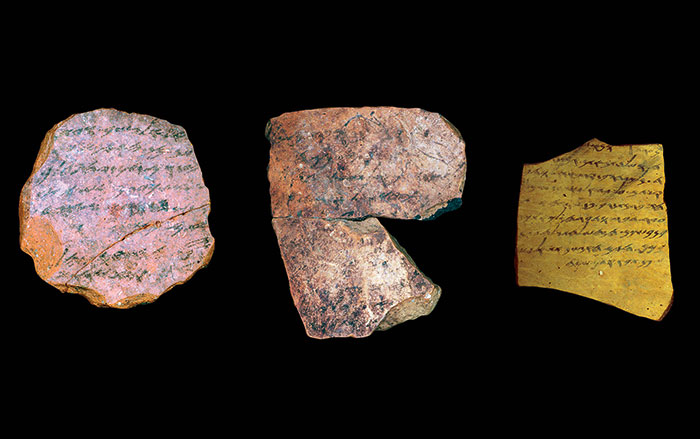

King and Strickland have also gone back to look at previously recovered artifacts, many of which were found decades ago by property owners on sites that have never been systematically excavated. One of these, called Leedstown, is located on the river between Fones Cliffs and Portobago Bay, and was once home to the Rappahannock town of Pissaseck. A cache of cut-crystal and glass beads of European origin was discovered there in the early twentieth century along a pathway to the river’s edge. The cache was first created in the 1650s or 1660s, during the early years of English settlement in the area. It appears to have been supplemented at least twice. The first set of additional materials was deposited some 20 years later, likely following Bacon’s Rebellion, a popular uprising against the Virginia governor asserting the rights of settlers to expand their territory. These offerings may have been stashed by Native Americans to secure spiritual protection in the face of increasing hostility from and violence committed by Europeans. The second addition came in the mid-eighteenth century.

During recent excavations at Leedstown, the team uncovered Indigenous ceramics, including fragments of Potomac Creek Ware and Townsend Ware, as well as more beads, which appear to have been scattered around the site by farming activity. King and Strickland say that the striped beads in the cache, and similar examples, were probably made in Italy. They are found almost exclusively at contemporaneous Native sites ranging from Pennsylvania to Florida. According to King, their distribution at Native sites beyond Leedstown suggests that the network of trade in animal skins, enslaved Indians, and guns that began in Virginia in the seventeenth century had expanded to cover much of the eastern seaboard by the turn of the eighteenth.

In an example of the duplicate place-names recorded by Smith on his 1608 map, there are two sites called Cuttatawomen. One lies at the mouth of the river and the other just west of the modern town of Port Royal, some 60 miles upstream. Strickland says that the relationship between the two towns was a mystery until he thought about differences in the ceramics that have been found at various sites along the river. “You can almost make a plot of ceramic types by type of temper along the river,” he says. Temper refers to material mixed with clay to prevent shrinkage and cracking when ceramic vessels are fired. Upstream, he explains, it’s more common to find ceramics made with a tempering method using crushed quartz, while farther downstream it is more common to find ceramics that have been tempered with ground shells. “At one particular site identified with the upriver Cuttatawomen, we examined an assemblage of nearly all shell-tempered ceramics,” says Strickland. He believes that the people who settled the Cuttatawomen site at the mouth of the river may have traveled upriver and brought their ceramic traditions with them. “Whether it’s a colony or an important ceremonial place, we identified some really interesting ceramics that were highly decorated and unusual,” he says.

Evidence that the Rappahannock traveled across the landscape doesn’t surprise archaeologist Martin Gallivan of the College of William and Mary, who has excavated a number of pre- and post-contact Native sites in the Chesapeake, including Chief Powhatan’s capital at Werowocomoco on the York River. “The John Smith map is a great resource,” Gallivan says, “but it does apply a fixity and boundedness to these Native societies that doesn’t line up with the evidence on the ground.” In his own projects, Gallivan has discovered evidence that Native communities in the region were connected through exchange networks across the Chesapeake and north to New England, south to the Gulf of Mexico, and west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. “People were on the move, they were travelers, and they visited other communities,” he says. “They had broad geographic knowledge and they could draw accurate maps covering hundreds and hundreds of miles.”

Perhaps because of the density of Native settlement in the Rappahannock River Valley, colonial authorities forbade settlers from moving into the region until the 1650s. This led to the area’s becoming a refuge for Native communities from as far afield as North Carolina whose lands had already been seized. It was at this point, according to Richardson, that the identity of the modern Rappahannock Tribe began to take shape, particularly after the Nanzatico were nearly all captured by the English and sold into slavery in the Caribbean in retribution after a band of their warriors was accused of killing the members of a white settler family. “We became the dominant tribe on the river and took in the various peoples who had been dispossessed of their land,” Richardson says. “I think that it’s very important to note that scholars who have looked at the Indigenous history of Virginia describe a great empire under Powhatan, but our leadership was really structured around taking care of and sharing the land.”

The nature of the Rappahannock’s relationship to Powhatan and his dominion has been the source of debate for at least a century. Smith mentions no antagonism between the Rappahannock and the Powhatan Confederacy. Richardson points out that the powerful chief’s own brother took Smith to a Rappahannock town—possibly because Smith was suspected of having killed the community’s leader. This act, she says, suggests a relationship of relative mutual respect between the peoples. Still, one curious element of Smith’s map has stood out to scholars; namely, that nearly all the Rappahannock settlements included on it lie on the river’s north bank.

Before conducting their excavations, the team developed a GIS model to find locations with environmental attributes favorable for establishing Native settlements. These included rich soil, a nearby source of freshwater, transportation waterways and landing places for canoes, habitats for aquatic and terrestrial animals, and good visibility across the landscape. The GIS model, which is based in large part on publicly available environmental data, shows that such locations are found closer to each other and in greater number on the north side of the river. “Smith shows all of these villages on the north side of the river, and for a long time that was interpreted as a physical means that the tribes in the Rappahannock River Valley were using to distance themselves from Powhatan,” says King. “But what we found from GIS modeling is that there are very different environmental conditions on the north side of the river versus the south side, so there might have been more of an economic reason for choosing the north.” The model also helped establish a viewshed, the geographical area visible from any given location. “There are a number of ossuary sites along the Rappahannock, important monuments composed of human remains,” King explains. “We’ve found that known Rappahannock settlement sites are often within that viewshed, within the direct line of sight of these ossuaries.”

The researchers determined that there was also a seasonal dimension to the location of settlements. “We followed the resources we could gather as the seasons changed on the river,” says Richardson. “In the summer, we were primarily on the northern riverbanks, catching fish and growing corn where the soil is so rich.” In the winter months, the community would move to the south bank of the river to hunt, often engaging in communal hunts with neighboring groups. While her tribe has been deprived of many of its ancestral spaces, Richardson sees continuity between the past and current movement of her people around the landscape. The combination of memory and research will provide a connection back to the river. “Rappahannock means a place where the water rises and falls,” she explains. “We have been a cyclical people that have risen and fallen at certain times in history. When we left the riverbanks, we went inland into our hunting grounds, and eventually we returned to the river again.”