On a hillside rising from the Pisco Valley in southern Peru’s coastal desert, just over 20 miles from the Pacific, lies one of the most puzzling—and puzzled over—built features in the world. Known as the Band of Holes, it stretches for just under a mile and consists of thousands of circular depressions arranged in neat rows and divided into discrete sections. The band averages around 60 feet wide, and the holes range from three to six feet across and 1.5 to three feet deep. The array is known locally as Monte Sierpe, or Serpent Mountain, a nod to the band’s sinuous form as it wends its way up the barren slope. “It’s truly unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” says archaeologist Jacob Bongers of the University of Sydney. “You’re walking up this hillside, and it’s just more and more and more of these precisely aligned holes. It looks kind of like a lunar landscape—it’s otherworldly.”

Indeed, many who are so inclined aver that the Band of Holes must be the work of extraterrestrials. Scholars, on the other hand, have proposed a range of possible purposes, drawing on parallels from around the world. Some have argued that the seemingly endless rows of depressions were designed as a geoglyph, akin to the Nazca Lines, 80 miles to the south. “It doesn’t look like any other geoglyph in the Andes,” says archaeologist Charles Stanish of the University of South Florida. “But, then again, it doesn’t look like anything in the Andes.” Others have noted the band’s resemblance to networks of shallow holes in which spikes were placed to defend late first-millennium b.c. settlements in Scandinavia. But no evidence of strife—much less an adjacent settlement to defend—has been found at Monte Sierpe. Many have insisted the holes held rainwater or captured fog and played a role in agriculture, based on comparisons with similar depressions in the Canary Islands used to grow wine grapes. But rain, fog, and groundwater are extremely scarce to nonexistent in the area, and the Pisco River has been used for millennia to irrigate the fertile valley, making hillside gardens both impractical and unnecessary. “Just because something is structurally similar doesn’t mean it’s functionally similar,” says Bongers. Likewise, suggestions that the holes might have served as tombs or mining test pits have fallen by the wayside given the absence of human remains or traces of metal ores.

In 2015, Stanish, then of the University of California, Los Angeles, and archaeologist Henry Tantaleán of the National University of San Marcos examined the Band of Holes and concluded that it had been built by the Inca in the fifteenth century. (See “An Overlooked Inca Wonder.”) Evidence such as Inca-era pottery found at the site and Inca tombs discovered at the base of the hill strongly suggested that the band dated to this period. There were also Inca storehouses nearby, and the Band of Holes lay along a road connecting two major Inca administrative centers in the hills, Lima La Vieja and Tambo Colorado.

A discovery made in 2014 at Inkawasi, another Inca administrative center 75 miles north of Monte Sierpe, provided an important clue to how the holes might have been used. Inside a storehouse at the site, archaeologist Alejandro Chu of the National University of San Marcos found that the floor was divided into a grid. Piled on the grid’s squares was produce such as peanuts, black beans, and chili peppers that had been preserved for some 600 years. Amid the foodstuffs were khipus, accounting devices the Inca used to track payments of tribute. A khipu consists of a horizontal cord from which hang groups of strings that can be knotted to tabulate data. In some cases, the knots on the khipus at Inkawasi matched the quantity of goods in their respective piles. It appeared that vassals of the Inca had been required to deposit tribute on the squares. Stanish and Tantaleán proposed that the holes at Monte Sierpe had once served a similar purpose. “The people down in the valley were producing commodities,” says Stanish. “They brought them up and left them in the holes. The Inca would count them and then their administrators in Tambo Colorado would come down and collect them.”

Bongers had been fascinated by Monte Sierpe since he first visited the site around 2015, and when Stanish asked him to map the holes using a drone in 2023, he leapt at the chance. The mapping yielded a more precise count of the number of holes in the band—approximately 5,200—and allowed the researchers to identify previously unrecognized mathematical patterns in the arrangement of the holes. This added nuance to their understanding of how the Inca likely used the site. Convinced there was more to be learned about the Band of Holes, Stanish and Bongers launched a project that involved revisiting the site’s date and analyzing botanical remains left in the holes. Their results have established that Monte Sierpe wasn’t actually the handiwork of the Inca, but of an entirely different kingdom that controlled the area before they arrived. The researchers believe the rulers of this kingdom designed the Band of Holes to serve a purpose that was vital to their success and that the Inca later expropriated it for use as a tribute depot. “I was pretty sure it was Inca the whole way,” says Stanish. “I was wrong about that.”

One of the challenges to understanding how the Band of Holes was used is the dearth of artifacts found at the site. Through careful documentation, however, Stanish and Bongers identified a larger sample of potsherds lying on the surface than had been available a decade earlier. Based on the sherds’ style, they concluded that some dated to the Late Intermediate Period (ca. 1000–1400). At this time, the powerful Chincha Kingdom ruled over the Pisco Valley and the neighboring Chincha Valley. The researchers also determined that sherds found at a defensive settlement located around a half mile east of the Band of Holes date to periods when the Chincha were in control as well as to periods when the Inca ruled over them. The team managed to retrieve a chunk of charcoal from one hole, which they radiocarbon dated to between 1305 and 1410, providing additional evidence that the holes had been dug and the site had been employed before the Inca moved into the region. “The Inca were in the Chincha and Pisco Valleys by the start of the 1400s,” says Bongers. “So we have pretty solid evidence that the site was in use before they got there. What we don’t know yet is over what period of time the site was built and used.”

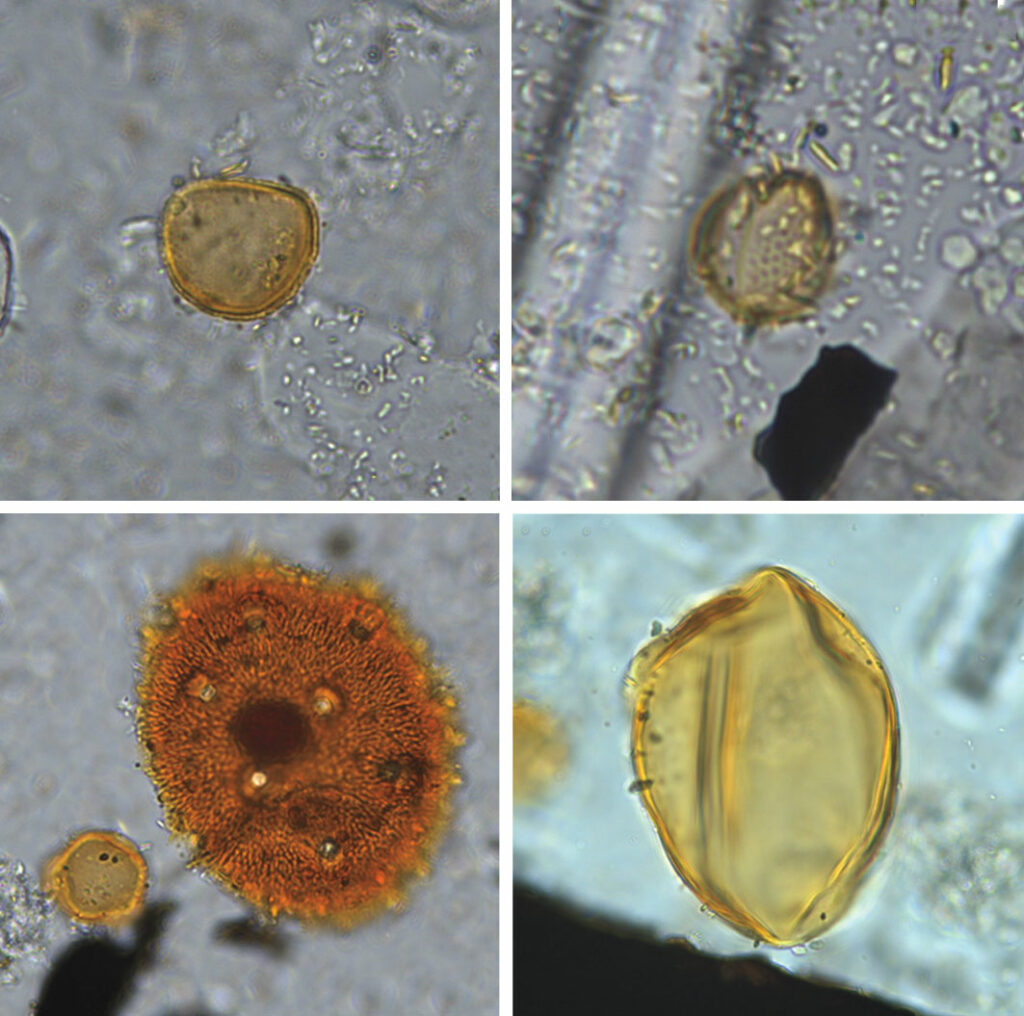

To dig deeper into the purpose of the holes, archaeologist José Román Vargas of the Peruvian Institute of Archaeological Studies collected soil samples from 19 of the depressions so they could be searched for microscopic botanical remains. Laboratory analysis revealed pollen from maize as well as from plant families that include cotton and chili peppers. The analysis also identified pollen from Humboldt’s willow and bulrush, both of which have been used in the region for millennia to weave baskets and mats. The presence of a significant amount of pollen even at the most elevated parts of the site, distant from agricultural fields, suggests that it was not transported by insects or the wind. Thus, the pollen must have piggybacked its way to the holes along with plants and plant products brought there by people. Based on these findings, Stanish and Bongers conclude that the depressions were used to hold baskets or bundles that contained produce. “People were putting goods in the holes, probably storing them there for some time, and then moving them somewhere else,” says Bongers.

This scenario accords with Stanish’s original hypothesis that local people left tribute in the holes during the Inca era. To determine how the Chincha might have used the site, Stanish and Bongers considered what is known of the kingdom’s economy, as well as the nature of the landscape the Band of Holes traverses. The Chincha Kingdom’s population is estimated to have been more than 100,000, based on colonial reports that there were 30,000 male heads of household in its former territory paying tribute to the Inca when Spain conquered the area. The Chincha population consisted of accomplished artisans, skillful fishers, farmers who tended crops in expertly irrigated valleys, and intrepid merchants who pursued trade in far-flung locales, plying the Pacific Coast on balsa rafts and driving llama caravans up and down the Andes. Chincha merchants handled goods such as copper, silver, gold, and guano—a potent fertilizer consisting of seabird excrement likely harvested by Chincha seafarers from the Chincha Islands, some 10 miles offshore. “The Chincha Kingdom was one of the wealthiest pre-Inca polities on Peru’s south coast,” says Bongers. “They were particularly famous for their mercantile activity.”

The Band of Holes occupies a transitional zone between the coastal plain and the highlands known as the chaupiyunga, the sort of area where people are known to have met to exchange goods. The site is also located near an important trade route connecting the coast and the highlands, as well as routes heading north and south. Given the Chincha’s mercantile prowess, Stanish and Bongers believe they designed the Band of Holes as a vast open-air emporium where they could exchange wares among themselves and with others. These trading partners could have included denizens of the highlands, who had access to potatoes and camelid fibers, as well as the lords of the Ica Valley to the south, who traded in precious metals and Spondylus shells. “Functionally, Monte Sierpe is in the perfect spot for a barter marketplace,” says Stanish. “It’s an open area. It’s on these highways. You can imagine big festivals with people in multicolored clothing coming from all around to trade.”

Different sections of the Band of Holes might have been the domain of particular families or groups, akin to market stands. It’s possible that people would agree to fill a certain number of holes with one commodity, which their trading partners would retrieve and then leave behind an agreed-upon quantity of another item. “Barter marketplaces are built around shared understandings of value or equivalency,” says Bongers. “We think that the holes may have served as units of exchange: ‘I have twenty holes of maize, which you can see right here because it’s out in the open, and I want ten holes of cotton.’”

Stanish and Bongers believe that when the Inca encroached upon Chincha territory in the early fifteenth century, the new arrivals saw the potential of Monte Sierpe to facilitate collection of tribute. “As a big empire, the Inca don’t like marketplaces,” says Bongers. “They see something like this and think, ‘We don’t want these people to be exchanging resources among themselves. We want the resources. Let’s appropriate this and turn it into an accounting device.’” Where once the Chincha had allotted portions of the Band of Holes for use as market stands, the Inca now reorganized communities into new groups that were assigned to fill the holes in designated sections with tribute.

Based on their detailed drone images, Stanish and Bongers were able to develop an understanding of Monte Sierpe’s layout that would have required countless tedious hours of ground survey. They established that the band is divided into at least 60 sections snaking up the hill, with crosswalks separating one portion from another. The researchers also detected uncanny patterns in how holes were arranged. One section has at least nine consecutive rows with eight holes each. Another has one row with eight holes and then six consecutive rows with seven holes apiece. Yet another has at least 12 rows that alternate between seven and eight holes. “We don’t know the meaning behind these patterns,” says Bongers, “but they definitely speak to an underlying purpose and intention in the design of the site.” In some places, notes Stanish, new holes appear to have been “squished in,” possibly to help create or maintain patterns. “They’re going out of their way to make it mathematically precise,” he says.

Stanish and Bongers suggest that a parallel to the arrangement of the Band of Holes may be found in khipus. “The band is the cord, the sections are the hanging clusters, the rows are the strings, and the holes are the knots,” says Stanish. “That’s a nice analogy, and it certainly makes sense.” An unusually large khipu discovered around the turn of the twentieth century near the city of Pisco, 20 miles west of the Band of Holes, comes close to matching the band’s layout. This khipu has 80 clusters of knotted strings, and the clusters generally contain between 10 and 12 strings, which is similar to the number of rows found in many of the band’s sections. “The relationship is not one to one,” says Bongers. “But the fact that this highly unique site is in the same valley as an incredibly unique khipu—and that their structure is similar—suggests that something is going on here.”

Perhaps another khipu will be uncovered that more precisely matches the layout of the Band of Holes. Or perhaps the band itself should be seen as what Bongers terms a “landscape khipu.” Everywhere else in the Inca Empire, tribute collectors diligently tied knots to record the offerings expected from diverse groups of people. But here, on a desolate hillside above an extraordinarily productive valley, they made use of a one-of-a-kind feature to communicate their requirements. Here, their demands were written into the earth in rows upon rows of holes, extending as far as the eye could see, just waiting to be filled with the region’s bounty.

Videos: Aerial Views of the Band of Holes

These videos offer a bird’s-eye view of the Band of Holes, one of the world’s most enigmatic built features. Rising from the Pisco Valley in southern Peru’s coastal desert, the band continues for nearly a mile into the foothills of the Andes. Drone imagery such as this has enabled archaeologists Charles Stanish of the University of South Florida and Jacob Bongers of the University of Sydney to arrive at a more precise count of the number of holes—approximately 5,200—and to identify previously unrecognized mathematical patterns in the arrangement of the holes. Videos courtesy J. L. Bongers.