On a Tuesday morning in fall 2013, Mike Collins loaded up his RV and started the 11-hour drive from his home in Austin, Texas, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Collins was en route to the Paleoamerican Odyssey conference, where he and other researchers would lay out their evidence, gathered from sites throughout North, Central, and South America, as part of the ongoing effort to piece together a picture of how and when humans settled these lands millennia ago. It was the biggest gathering of its kind since 1999.

Collins, a Texas State University archaeologist, had precious cargo with him in the form of more than 70 stone tools that he’d found during his 15 years of digging at a site in central Texas, roughly midway between Dallas and San Antonio, called Gault. His collection was scrupulously organized into two groups—one that he believes are more than 13,000 years old and a second that he believes were made more recently. The tools—blades, scrapers, and bifaces (typically crafted carefully on both sides)—initially appear to share similarities, as if all are part of the same lineage. But three points in the “newer” collection exhibit striking work—“stemmed” ends and fluting—of a caliber not seen in the other cache. These points, to which the term “beautiful” is often applied, are Clovis points. For the last several decades, in addition to capturing everyone’s attention because of the skill that making them requires, Clovis points have been thought to have been made by the first people to inhabit the Americas. Assemblages of artifacts such as Collins’, painstakingly excavated over years, form an ever-advancing line of research into the population of the Americas.They are a primary means of overturning the long-standing theory that a group of big-game hunter-gatherers crossed over a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska, known as Beringia, making their way south through an ice-free corridor in western Canada around 13,000 years ago. From there, they would have radiated onto the continental United States and beyond, all the way down to Chile.

It has been a compelling narrative. But recent excavations at Gault are part of a growing list of digs contributing new evidence that not only asserts that there were other peoples in the Americas at the same time as those who made Clovis points, but that humans had reached these lands earlier, and possibly by different routes. At the conference, when it was Collins’ turn to speak, he said just that. “By the beginning of the Younger Dryas [a 1,300-year cold snap that began about 12,800 years ago], this was already a fairly crowded archaeological landscape.”

Over the past 15 years, as the consensus in the field has gradually moved beyond the idea that “Clovis came first,” archaeologists have arrived at what Collins calls “an enormous and propitious moment in the study of the peopling of the Americas.” The door has been thrown open to discussions of multiple founding populations, alternate routes, varying toolkits, and even drastically different timeframes for when people might have shown up. “Clovis is still important,” says Mike Waters, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University, “but we have to realize that there were people here before. Now we have to determine how long before Clovis people were here, who they were, what kind of technology they carried, and how they migrated through the continent and settled the empty landscapes.”

It’s a new, exciting paradigm in the field that could possibly confirm that the melting pot that the Americas are today is not just a recent development. “We can look at things now in a totally different light,” says Jim Adovasio, director of the Mercyhurst University Archaeological Institute in Erie, Pennsylvania. “The book is wide open for new inscriptions.”

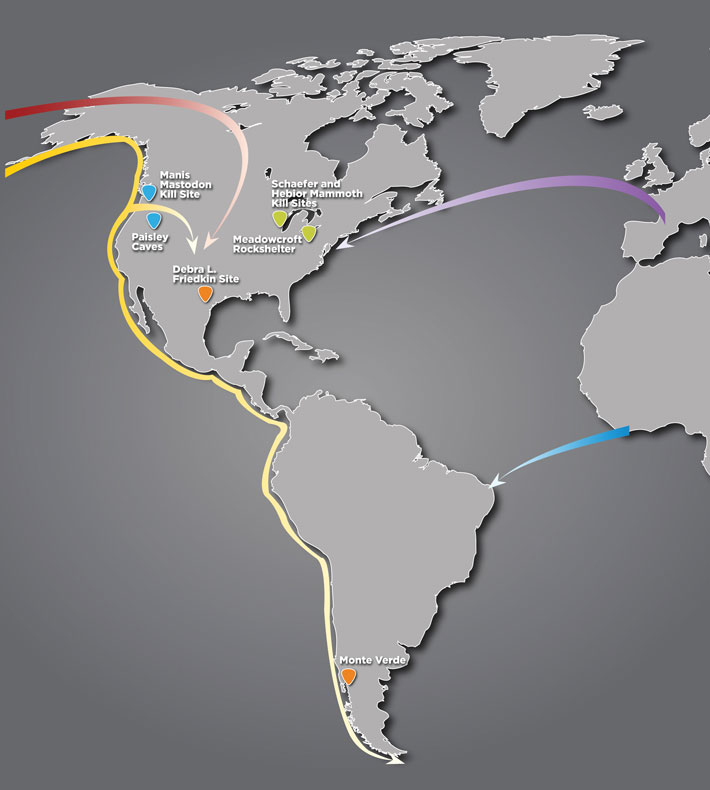

One of the initial clues that people had arrived in the Americas before Clovis came from the southernmost tip of the hemisphere: the Monte Verde site in Chile, 600 miles south of the capital, Santiago. In the late 1970s, an excavation led by Tom Dillehay, currently at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, turned up stone pebble tools and wood and bone artifacts dated at more than 13,000 years old. Remnants of living quarters and three human footprints discovered there also appeared to be from the same period. The revelation would lead to more than two decades of controversy about the integrity of the site, until, in 1997, a group of nine prominent archaeologists traveled to Monte Verde to assess its legitimacy. After sitting through a series of presentations—from, among others, Dillehay, Collins, who spoke about the stone tools discovered there, and Adovasio, who had studied the ropes used on a tent structure that had been found—and taking a visit to the site, the panel was satisfied that the site contained evidence of occupation dating back 14,500 years, some 1,500 years before the date of the earliest Clovis site in the Americas.

Today, the archaeological community has largely come to accept that people were living at Monte Verde before the emergence of Clovis technology. Adovasio, whose excavations at Meadowcroft Rockshelter in the 1970s uncovered artifacts indicating that people were living in western Pennsylvania between 14,000 and 16,000 years ago, says that now, looking back, he realizes that he and Dillehay vastly underestimated how long it would take for their findings to be accepted. And the work continues. At the Santa Fe conference, Dillehay offered a presentation on Monte Verde and one on a site in northern Peru called Huaca Prieta, where he’s found charcoal and animal bones along with stone tools dating back as far as 14,200 years.

As things now stand, the work of this group of archaeologists and many others is continuing to offer up enough evidence to keep researchers busy for the next several decades. Some of the upwards of 50 sites already being studied will have their findings permanently written into the story of the peopling of the Americas. Take, for instance, Paisley Caves in southern Oregon. There, archaeologists discovered fossilized human dung, called coprolites, and a few pieces of a stone toolkit that looks nothing like Clovis, but is, at the least, contemporary with it.

The earliest dates at Paisley are 14,300 years ago. Based on analysis of the coprolites found there, Dennis Jenkins, the University of Oregon archaeologist who led the excavation, has been able to determine that the people there were gathering and consuming aromatic roots, for which they would have needed special knowledge that would have developed over time. “These guys aren’t the first people to come over the hills, see the caves, and go in there and relieve themselves,” he explains.

In addition, Paisley Caves provokes a line of questioning having to do with the routes that early people might have taken to reach the Americas. There are dissimilarities between the tools found at Paisley and Clovis points. In addition, people in the area of Paisley Caves were there before 14,300 years ago. Rather than these people being part of the same group whose descendants would eventually make Clovis tools, the inhabitants at Paisley were, instead, a distinct and earlier pulse of migrants. That raises the question of whether all of the earliest humans in the New World actually entered via the ice-free corridor. Jenkins, in fact, supports the hypothesis that the original immigrants to America boated from island to island along the northern rim of the Pacific, eventually making it from Beringia to the Pacific Northwest around 15,000 years ago.

Some of the coastal travelers may have made their way inland to what is today northern California, following the Klamath River northeast to Paisley Caves. Others, Dillehay suspects, might eventually have followed the coastline all the way to Monte Verde. “After the initial entry,” he says, “it is highly likely that this is one large tossed salad, with multiple migrations from multiple places moving around and retracing, with some on a straight line south.”

Other archaeologists working in South America, however, have a different idea. Stone tools found at the Toca da Tira Peia rockshelter, in Serra da Capivara National Park in central Brazil, have been dated to 22,000 years ago. At Pedro Furada, another rockshelter in the same park, excavators say they’ve found tools and fire pits dating back 50,000 years. If either claim is confirmed, it would suggest that the first Americans arrived in the southern hemisphere, possibly via boat from west Africa, where the Atlantic is at its shortest width, around 1,600 nautical miles.

If there’s a new buzzword in the archaeological study of the peopling of the Americas, it is “boats.” Part of reimagining the settling of the New World is to stop considering traveling by land as the only way people could have arrived there. “We so radically underestimated the roles of boats and water transports for all time horizons, not just the more recent past,” Adovasio explains. After all, roughly 50,000 years ago aboriginal Australians completed the trip from East Africa to Oceania. More specifically, they got there via Asia, “and they sure didn’t walk,” says Collins. Evidence shows—and this is an important understanding to factor in when considering all of these migrations—that the “trip” took them 20,000 years.

Nonetheless, the migration proposal that arouses possibly the highest degree of contention relies on boats. It suggests that the earliest travelers to the New World made their way more than 20,000 years ago from what is now the west coast of France and northern Spain. They went north along the coast to what is now southwestern Ireland and then west along the edge of an icecap in the northern Atlantic Ocean until they reached North America at the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. They would then have made their way south. This argument rests on the discovery of laurel-leaf biface points that strongly resemble tools used by the Solutrean people, who lived in France and the Iberian peninsula from about 22,000 to 17,000 years ago. They have been found in several locales including the Cinmar site off the coast of the Delmarva Peninsula near the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. The archaeologists who support this theory stress the similarity between Solutrean and Clovis tools. They consider the Clovis point the direct descendant of the laurel-leaf tool.

Not all researchers are willing to embrace what is commonly termed the Solutrean hypothesis. Waters, for instance, doesn’t buy it. “I think there are just too many problems,” he says, referring to, among other criticisms, the lack of a systematic excavation at any of the sites where the points have been found. Collins, however, who is open to hearing out the vast majority of pre-Clovis claims, finds the Solutrean hypothesis very compelling. “I think maritime adaptations happened in both oceans, and I think it happened first in the Atlantic and then the Pacific,” he explains. “You have people peopling the Americas from both directions, and they eventually meet in the middle.”

The work proceeds from site to site. While Waters tends to support the validity of a total of 10 “before-Clovis” sites in the Americas, Collins is considering the possibility that there are already around 40 such sites. “When you look at the big picture, it looks like there’s an extraordinarily complex early record out there,” says Collins, who is already looking for patterns among sites. “I think by 14,000 years ago there were a lot of people here.”