The skyscrapers of Rotterdam rise high above the banks of the Nieuwe Maas, a channel of the Rhine Delta, whose rivers snake their way across most of the southern Netherlands. Lying some 20 miles upstream from the North Sea, the city’s port is a vital trading center that connects the industrial heartland of Europe with the rest of the world. In this forward-looking, modern metropolis, the country’s second largest, almost no two buildings look alike, and its futuristic appearance is a stark contrast to more traditional Dutch cities, such as Amsterdam or Delft. Rotterdam’s Centraal train station, for example, is all angles and sharp lines with a tip that points new arrivals in the direction of the city center. The public library is covered in creeping yellow tubes, while the nearby flying saucer of the Blaak metro station seems poised for takeoff. The city’s newest architectural marvel is the Markthal, a massive covered market hall in the shape of an upended horseshoe that stands near the fifteenth-century St. Lawrence Church. Extensive excavations here have revealed that the hypermodern Markthal lies above what was once the very heart of medieval Rotterdam. “The St. Lawrence Church is the only medieval remnant you can see,” says Arnold Carmiggelt, chief of Rotterdam’s archaeological bureau. “The only other medieval structures are underground.”

The reason so little of medieval Rotterdam survives is that on May 14, 1940, the German Luftwaffe carried out a devastating raid on the city. That attack and the ensuing fire left only a handful of buildings still standing. The redevelopment of Rotterdam and its port after World War II took decades, and while its citizens built for the future, they found themselves constantly encountering their city’s history. “As people were cleaning up, and later when rebuilding, they would find items from the past—tiles, earthenware, medieval and postmedieval artifacts, as well as locks and sluices,” says Carmiggelt. “Because everything had been lost, they were very interested in these objects from the past.” The city’s archaeological bureau, the Netherlands’ first such municipal agency, was founded in 1960 primarily because there were so many accidental historical discoveries.

When construction on the Markthal began in 2009, the bureau was faced with both its biggest opportunity and its toughest challenge. Officials knew the structure’s planned four-level underground garage would destroy any archaeological remains that lay in its way. Excavating ahead of the structure meant digging to a depth of 40 feet, well below sea level. “Constantly seeping groundwater would make archaeological work impossible,” Carmiggelt says, “so we worked with geotechnicans to make a system to keep water out of the excavation.” Working on a tight deadline through winters, in harsh conditions, the team made a series of discoveries that peeled back the history of Rotterdam to the time of the city’s founding and even earlier. The waterlogged earth that made excavation difficult meant that the wooden structures and many artifacts found in garbage layers and cesspits, never exposed to oxygen, were extremely well preserved. They provided remarkably clear evidence of how the earliest generations of Rotterdammers struggled to coexist with the same sea that would eventually enable a small, wet settlement of a handful of farmers to grow into a bustling medieval center, and eventually into one of the world’s most consequential cities, with the largest port in Europe.

Some of the earliest known inhabitants of what became Rotterdam lived during the Roman period, when the southern Netherlands were part of the frontier province of Germania Inferior. They made their homes on marshy peatland near a fort that stood alongside the riverbank of the Old Rhine, the northern border of the Roman Empire. In addition to Roman-era ceramics found at the very bottom of the Markthal excavations, city archaeologists also discovered wooden locks, trenches, and ditches that were all used in attempts to control water levels even then. After the Romans withdrew from the area in the second half of the third century A.D., the population steeply declined, in part because rising sea levels eventually made the region uninhabitable.

It wasn’t until A.D. 900 that the first pioneering farmers returned to the riverbanks of what was by then known as the Rotte (meaning “muddy water”) River. A farmstead is first mentioned in a charter dating to 1028, which describes a church of Rotta (a Latinization of “Rotte”) that belonged to Hohorst Monastery, which in turn was part of the vast Germanic Holy Roman Empire. To the surprise of the city archaeologists, they found extensive remains dating to this period during the Markthal excavations. At a depth of some 33 feet they encountered a well-preserved terp, or a raised earthen mound, on which they found the remains of six distinct farmsteads dating from 950 to 1050.

In the terp’s trash heaps archaeologists discovered a wealth of plant remains, mainly oats, barley, and emmer wheat, that offer a look at what the Rotta farmers cultivated. They also found fragments of hand-operated mills—used to grind the grain—that were made from tephrite, a volcanic rock from Germany’s western Eifel region, roughly 200 miles away. Animal bones from cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, small chickens, and geese suggest the variety of animals the people of Rotta raised. The farmers appear to have lived with their livestock in A-frame buildings that had wicker woven walls strengthened with clay and sloped reed roofs. Soil samples taken from inside one of the houses on the Rotta terp showed a high amount of nitrate, a byproduct of fecal material, in one section, which was likely the house’s indoor “barnyard.”

In one of the garbage layers of the terp, the team found a small bone object with three points, resembling a trident. They were puzzled by the find, which is the first of its kind to be excavated. “We didn’t know what it did,” says city archaeologist Marjolein van den Dries. “So Leiden University made replicas of the item and then tried many different simulations on various materials.” Using a microscope, archaeologists compared traces of use-wear on the replicas to that on the original. The experimental research showed that the “trident” was used in wool processing, which also must have been an important activity in the Rotta farmstead.

While they may have enjoyed some success in farming and raising livestock, life for the residents of the humble Rotta village was difficult. Despite building their farms on the elevated banks of the river, the villagers were constantly threatened by flooding. The farmers tried to combat the rising water by draining the peat via small man-made canals, which are still visible in the archaeological record. But because peat settles much more than other soil types, when the land was drained, it lowered in elevation. In an area already prone to flooding, this only made the problem worse. “Their very way of life made it impossible to live there,” says van den Dries. Unable to overcome the wet conditions and frequent flooding, the Rotta villagers were forced to abandon their homes around 1050.

During the Middle Ages, local nobles with holdings along the Rotte constructed a series of protective walls to guard their own lands against flooding. But these individual dikes only resulted in raising the water levels along other sections of the river. Eventually, in 1270, the Count of Holland, Floris V, ordered the construction of a single sea wall to protect the region against floods. The resulting dike measured 1,300 feet long, 23 feet wide, and nearly five feet high, and was constructed across the river not far from the old Rotta village.

Above the remains of the abandoned Rotta farmstead, extensive traces of Rotterdam, the town created in the wake of the dike’s construction, were discovered by city archaeologists. Its proximity to the river Rotte and the North Sea was now not just a hardship to overcome, but had become a key to the local economy. The Rotte, in addition to functioning as a drainage system, became a trade route linking Antwerp, Bruges, England, France, and the Baltic region. Because the dike blocked direct passage through the Rotte, traders had to reload their goods on the other side or temporarily store them in Rotterdam, which turned the town into an important port (and market) for staple goods, such as beer and textiles, the latter linked to leaden textile seals that were found in the Markthal excavations. Many Rotterdamers also became involved in the burgeoning fishing industry. Rotterdam would become the most important city for herring in the region, with a fleet of 151 herring ships sailing out of its port by 1603. New techniques, such as herring curing, allowed for bigger catches, faster processing, and longer storage. A number of artifacts related to the fishing trade—fishing hooks, net weights, and needles for producing and mending nets—were found at the Markthal site.

Rotterdam began to grow quickly after it received a city charter in 1340 from Count Willem IV of Holland. This official recognition gave the city the right to dig a deeper shipping canal, creating a trading link with other Dutch cities, allowing it to become a local transshipment center connecting it with England and Germany. By 1358, Rotterdammers built new fortifications around the city. They expanded the dike in the middle of the fourteenth century until it measured 70 feet wide and nine feet high. A city seal, found in a layer dating to around 1400, depicts the importance of the river and the dike to the growing port. Made of wax and found in a copper box, it bears a vertical bar, which represents the river, coming to an abrupt stop where it meets a horizontal bar representing the dike.

Around this time Rotterdam’s officials created two polders, or areas of low-lying reclaimed land enclosed by dikes, to accommodate the growing population. “These were medieval housing projects,” says historian Jan van den Noort, “that consisted of houses and workshops.” The eastern section of Westnieuwland, one of the two polders, was where the Markthal now stands.

The excavations offered a remarkable picture of the evolution of houses built in the Westnieuwland polder. In the earlier levels, city archaeologists found the remains of wood houses roofed with thatch and fireplaces located in the center of the houses, while in the fifteenth-century sections of the site it is evident that houses were being built out of stone. Rotterdammers were becoming more prosperous and strove to meet city regulations that attempted to prevent large fires. This shift in construction materials also touched off a change in the kind of modest household items that were found in houses. For example, oil lamps unearthed at the site had two holes before the fifteenth century. A fire hazard if placed too near the wooden walls, the lamps were suspended from the ceiling by a cord strung through the two holes. Once stone came into use, lamps could be safely hung on walls, and only one hole was needed to secure them. Another testament to Rotterdamers’ preoccupation with fire is numerous examples of flat unglazed earthenware objects—medieval fire extinguishers—used to prevent embers from rekindling. By 1500, the threat of fire had been reduced to such a degree that houses were being built close together.

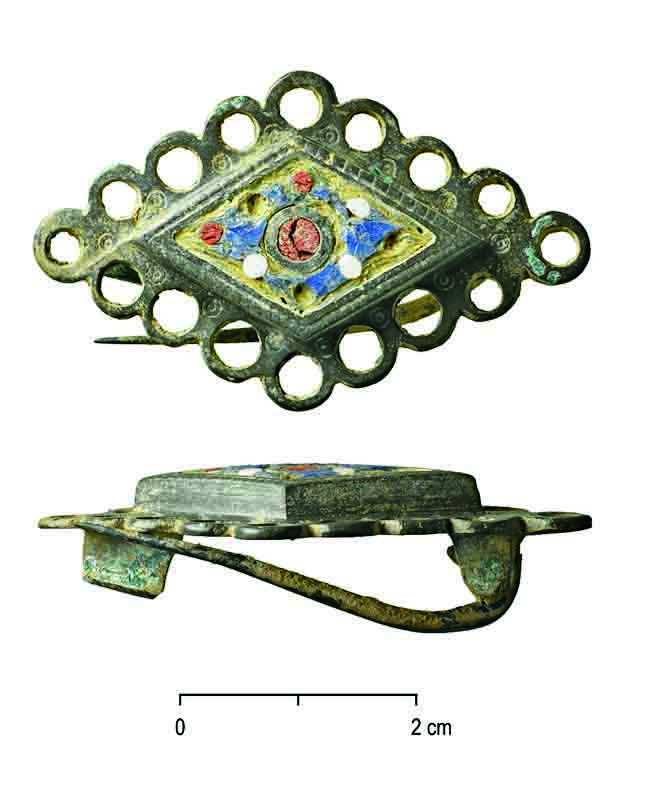

While construction of new houses on the Westnieuwland polder speaks to the city’s growing wealth, the trash pits behind them held evidence of the new importance of trading in the city’s life. Tin-alloy pilgrims’ insignias from foreign lands—Germany, England, Italy, France, and Belgium—suggest that international travel was becoming more commonplace. Also testifying to the city’s growing cosmopolitanism were the discoveries of minute quantities of fruits and spices such as olives, pomegranates, and pepper from the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia, as well as ceramics from Spain. By 1556, Rotterdam was subsumed by the Spanish Empire, which placed a high value on its strategic location at the entrance to the Rhine Delta. Even as it continued to be an important trading center, the city was poised to play a more important role on the world stage.

The year 1572 was pivotal for Rotterdammers. After Spanish soldiers killed two important locals, the city switched its allegiance from the Spanish Empire to the newly independent nation of Holland, then led by Willem van Oranje. Willem threw his support behind the city, building new fortifications and creating an inner harbor, which gave city merchants fresh opportunities to expand trade and shipping. In 1585, the Spanish King Phillip II forbade all commerce between the areas he ruled and the Netherlands. Refugee merchants fleeing Spanish-held Antwerp began to use Rotterdam to trade with overseas territories, and this, combined with growing trade with the Far East, meant Rotterdam became an even more important port.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Rotterdam was playing a major role in the rise of the trading empire of an independent Netherlands. Finds from this period speak to the increasing sophistication of the city’s inhabitants. A wide range of crockery made from varying materials was found in the Markthal excavations, some richly decorated, which demonstrate that in addition to beer and wine, Rotterdammers were now enjoying coffee and hot chocolate from the New World. Most goods related to daily life, such as meat, glass, clay pipes, textiles, and ceramics, were being imported from outside the city, which was by then focused almost exclusively on trade. By the eighteenth century, Rotterdam was even importing water in stoneware jugs, like one found during the excavations from Selters, a German town known for its high-quality mineral water. Still other finds from this period speaking to the city’s growing reliance on trade are two-eared jugs from Portugal. These jugs most likely were originally produced to transport olive oil, but in northwest Europe these jars have only been found in shipwrecks or harbor cities, probably taken home as personal belongings by the sailors who were becoming so important to Rotterdam’s economy.

Few artifacts or structures in the Markthal excavations that date to after the seventeenth century were discovered. But by that time, the historical record amply shows that the city was well on its way to becoming one of the most vital harbors in the world. Today the Port of Rotterdam stretches more than 25 miles in length and covers 41 square miles. Each year, some 30,000 seagoing vessels and 110,000 inland vessels sail in and out of Rotterdam, which handles some 465 million tons in cargo, making it by far Europe’s busiest port.

Inside the Markthal, gigantic and colorful fruits, vegetables, and even whole fish appear to rain down from the ceiling. Known as the Horn of Plenty, this photographic 3-D illusion, one of the largest art pieces in the Netherlands, refers to the great still-life cornucopias painted during the Dutch Golden Age in the seventeenth century. Below this vast celebration of the country’s past is an easily overlooked set of escalators, dubbed the Time Stairs. What could have been solely a method of returning to one’s car is actually a means of descending through Rotterdam’s historical eras. Near the escalators, artifacts from each occupation layer are displayed in small glass rooms on the floor closest to where they were discovered and excavated. At the very bottom of the escalators, some 50 feet below the Markthal, visitors reach the oldest part of the site, the end of their trip through time. The items here are small and sparse—a key, a knife blade, a pair of shears, a pile of animal bones. They are a reminder that a city that is now called Europe's gateway to the world was once a simple village struggling against the sea for its very survival.