In the Upper Paleolithic period, just over 12,000 years ago, Arene Candide in Italy’s northwestern Liguria region was an imposing cave with a massive, nearly 300-foot sand dune next to its entrance. Today, the dune has been quarried away. For archaeologist Vitale Sparacello of the University of Bordeaux, Arene Candide is key to understanding humanity’s legacy in the region. Sparacello grew up in Genoa, just about an hour east of Arene Candide, and has long been fascinated by the deep history the region has to offer. Unlike other caves, which have been studied mostly to see how people lived in them, for Sparacello and his colleagues, the site provides something else altogether—insight into how Paleolithic people buried their dead.

Arene Candide has 10 primary Paleolithic burials, two of which are double burials, and seven clusters of bones, totaling at least 20 individuals. There is a single burial, some 10,000 years older at the site, nicknamed the “young prince.” Piecing together the story of Arene Candide has not been easy. Working with the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage in Liguria, the Ligurian Archaeological Museum, the Archaeological Museum of Finale, and the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence, Sparacello combed through both the collections of human remains removed from the cave and the museums’ archives, in addition to participating in fieldwork at the site over several years, to illuminate what happened at the site during the Upper Paleolithic. “You always wish earlier excavations had done more, taken more notes, more photographs,” Sparacello says. “But it is humbling to see how much good work they did, especially when you go back to the field and realize that you are responsible for documenting your own generation’s excavations.”

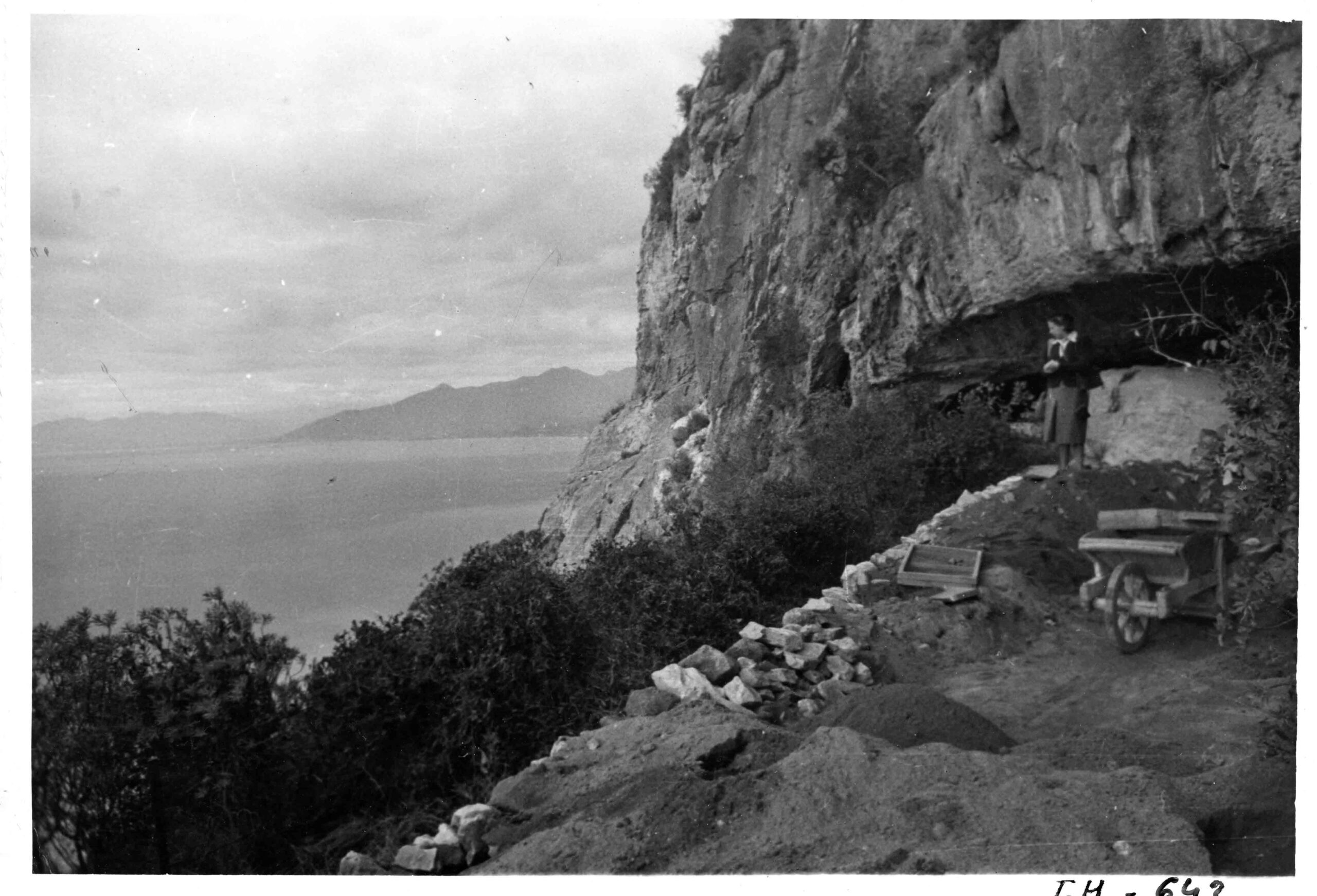

The upper, most recent, levels of Arene Candide were first excavated in the 1880s and were found to contain several Neolithic burials dating to 5000–4300 B.C. Six decades later, in the 1940s, archaeologists dug through the site’s middle layers and uncovered the Paleolithic individuals, dating to more than 12,000 years ago. They were interred beneath a thick rocky layer in the cave that separated the older from the younger strata. These researchers described Arene Candide as a necropolis, based on the plethora of Neolithic burials. More recently, Sparacello and his colleagues have been able to take that description even further, concluding that Arene Candide was a place that Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers visited time and time again in order to inter their dead. They did this for more than 500 years, nearly 20 generations.

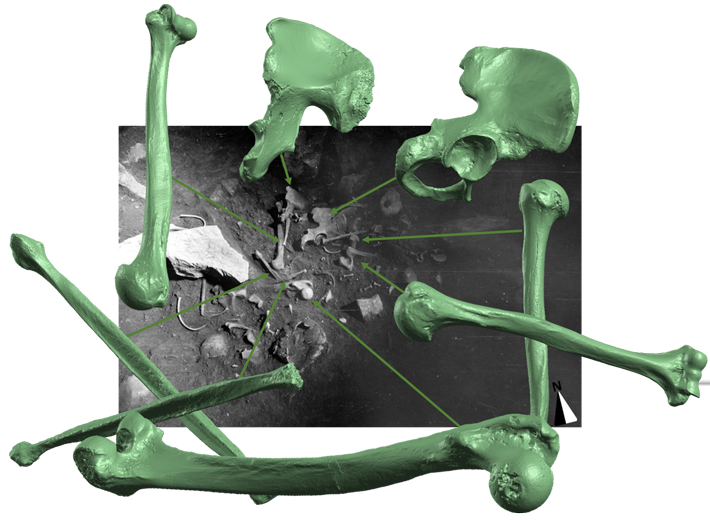

Sparacello’s research suggests that some of Arene Candide’s burials were intentionally moved from their original context. This happened in two distinct phases, separated by only a few centuries (10,820–10,420 B.C. and 10,030–9180 B.C.) But the older burials were not just haphazardly moved aside to make room for new bodies—the bones from the earlier burials were incorporated into the newer ones. Crania and other skeletal elements from the older burials were also integrated into the arrangement of stones that encircled the more recent examples.

Moreover, two individuals from different periods share skeletal anomalies, possibly related to congenital rickets. “This does not appear to be a coincidence,” Sparacello says. “People performing this funerary behavior knew whose bones were involved. We suggest that shared pathologies, especially congenital, may have been the focus of Paleolithic funerary behavior, particularly when it involved multiple individuals.” In addition, small, broken stones were found near the burial circles. Attempts to rejoin the halves of the pebbles have not been successful, leading researchers to propose that half a pebble was left with the dead while the other half was carried away as a talisman or souvenir.