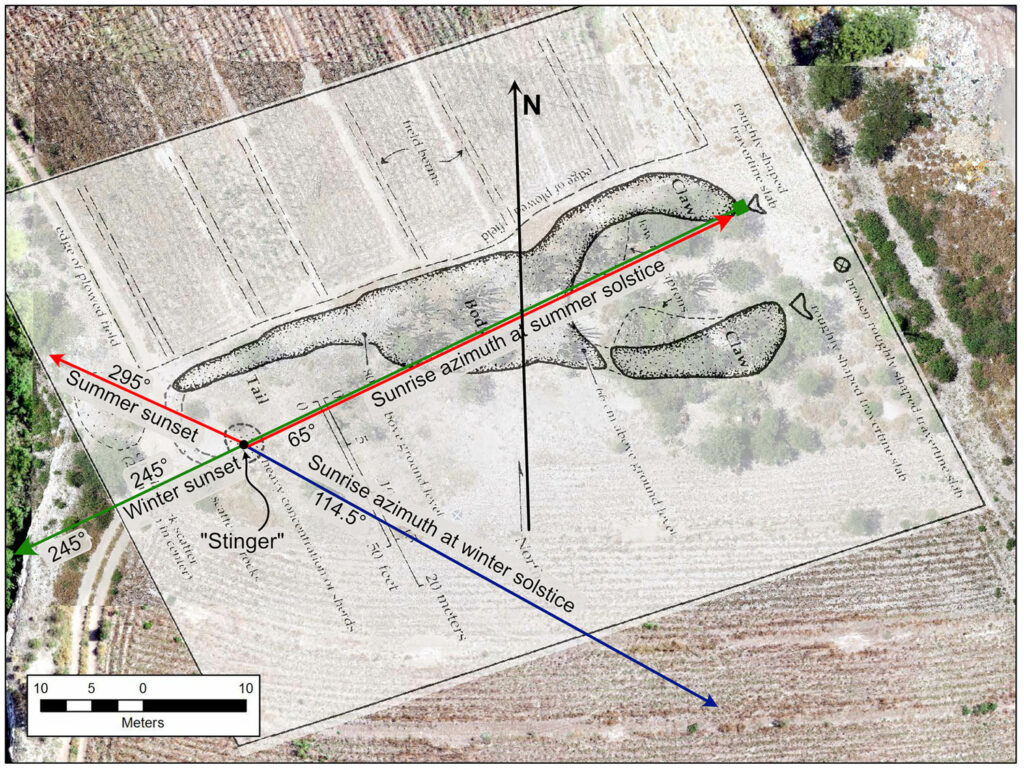

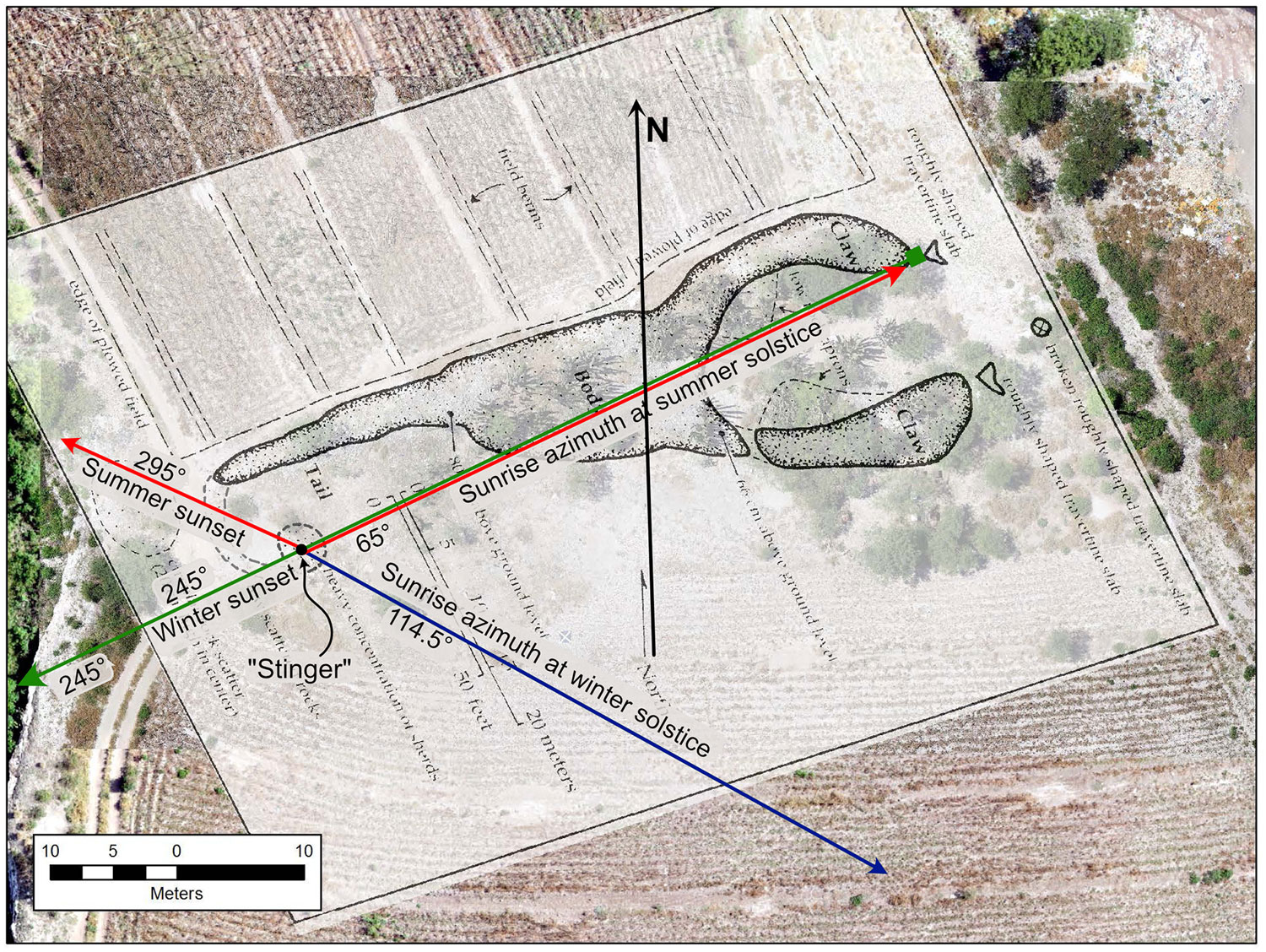

AUSTIN, TEXAS—According to a Live Science report, James Neely of the University of Texas at Austin and his colleagues suggest that country farmers used a 205-foot-long, scorpion-shaped effigy mound in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley to mark the winter and summer solstices from about A.D. 600 to 1000. The scorpion, which is oriented east-northeast, is one of 12 mounds in a complex covering about 22 acres. Made up of a mix of dirt and rocks, the surviving head, body, pincers, and tail of the scorpion stand about 30 inches tall. A collection of ceramic fragments was found buried at the “stinger,” or the tip of the scorpion’s tail. The researchers suggest that in the days leading up to the summer solstice, a person standing at the stinger would see the sun rise between the scorpion’s claws. It would eventually reach the tip of the mound's northern claw on the summer solstice, which would mark the beginning of the rainy and planting season. At the winter solstice, a person standing at the tip of the northern claw would see the sun set beyond the stinger. “It is the first indication that knowledge and control of astronomical phenomena based on solar observations was not totally in control of the elite class,” Neely said. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Ancient Mesoamerica. To read about the complex Mesoamerican calendrical system, go to "The Maya Sense of Time."