(Courtesy Kenneth King)

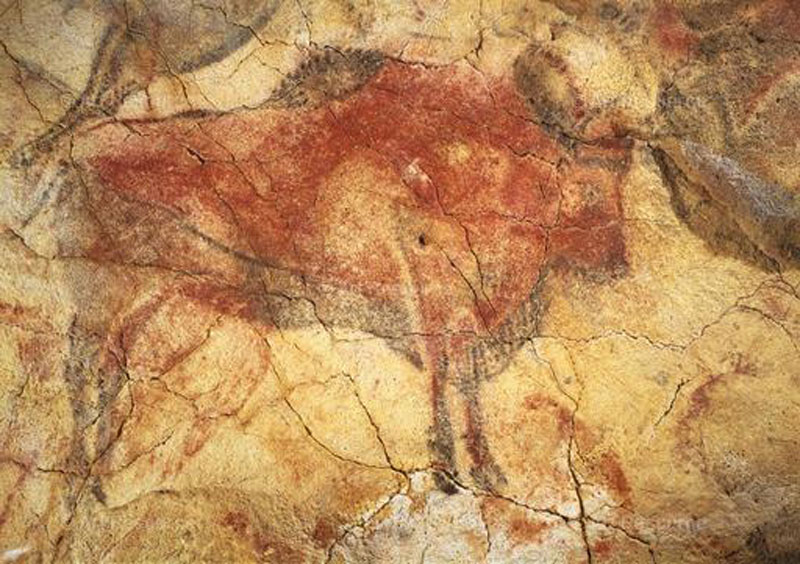

White Trace Branch is a narrow, wooded valley near the base of Blair Mountain, 50 miles south of Charleston, West Virginia. Today, only the grind of trucks downshifting on a nearby road breaks its arboreal hum. But in 1921, that sound was replaced by the rattle of machine guns and the pop-pop of squirrel rifles, when the valley was just one corner of a battlefield sprawling across 10 miles of ridgeline. In late summer of that year, a force of striking coal miners crept through this hollow, dodging fire from anti-union forces stationed above. The Battle of Blair Mountain, as it is called, involved more than 10,000 men and was the country's largest civil conflict besides the Civil War. Though the battle is little known outside of union and historian circles, it was a key moment for the American labor movement.

Long believed to have been lost to history, the remains of the fight, mostly in the form of fired bullets and spent shells, are scattered around Spruce Fork Ridge (of which Blair Mountain is just one peak), barely concealed by 90 years of forest litter. These munitions appear in telling patterns—a concentration here, a trail there, like an ant colony winding through places such as White Trace Branch, Baldwin Fork, and Crooked Creek Gap. In one place, five .32-caliber pistol shells rest together, likely marking the spot where a striking miner once stood. Details of the fight are sketchy—the miners were secretive and the coal companies cagey—but early archaeological study has begun to lead to a reevaluation of the battle and the success of the miners' forces.

However, outside of a few public roads and paths, such as the one through White Trace Branch, archaeologists are not allowed to enter most of the battlefield. And the mountain itself may not survive long enough to provide more answers. Blair Mountain, like many others here, holds coal. The battlefield lies within several concessions for the form of surface mining known as mountaintop removal, in which the peak of a mountain is sheared off to expose the coal beneath and deposited in a neighboring valley. More productive and profitable than traditional deep mining, mountaintop removal is widely criticized for its impact on the environment and local living conditions. At Blair Mountain, it has earned a few more vocal opponents.

White Trace Branch was the scene of one of the skirmishes of the Battle of Blair Mountain.

(Samir S. Patel)

The archaeology on the mountain, and the story it is beginning to tell, has helped bring together an unusual coalition—including the Sierra Club, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and a number of local organizations—in what some are calling "The Second Battle of Blair Mountain." It is certainly a fight over historic preservation, but for many involved, including local archaeologists and historians, the mountain is symbolic of much more—labor struggle, the social effects of resource extraction industries, and what they see as a century-long class conflict. The mountain's loss to surface mining, they assert, would be personal, a major blow to Appalachian identity.

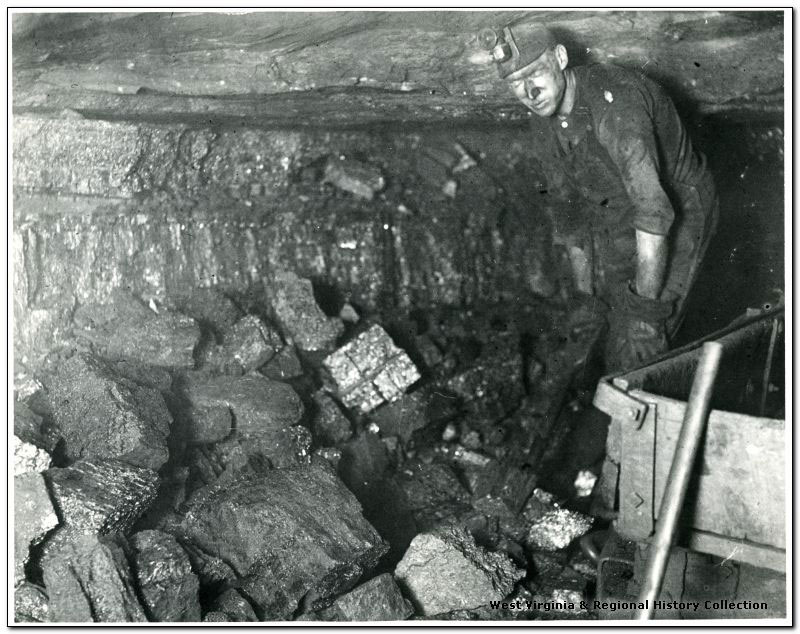

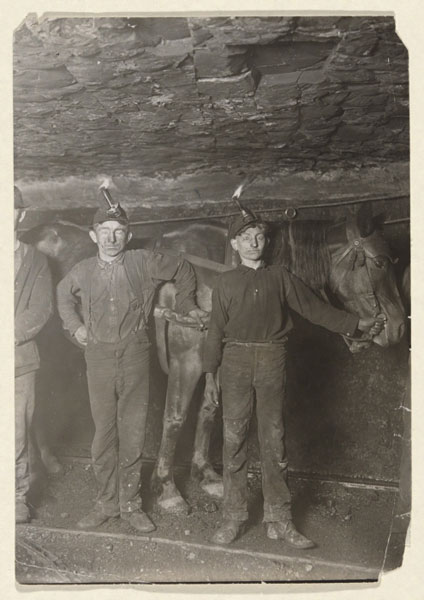

Coal mining has always been one of the most dangerous and difficult jobs, and the late nineteenth century in the southern coalfields saw it at its worst. There were few safety regulations for workers—undocumented European immigrants, African Americans, and poor Scots-Irish hill folk—and every aspect of their lives was controlled by their employers. They lived in company towns, bought their own equipment at company stores, and listened to company-approved sermons in company churches. As labor movements picked up elsewhere, even in coal regions to the north, they seemed to pass the southern coalfields by.

(Courtesy Kenneth King West Virginia and Regional History Collection)

The UMWA found a charged situation when the organization arrived in 1920. The bitterness that had been simmering boiled over the next year, with a prolonged strike, shootouts, guerilla fighting, and the imposition of martial law. Following the August 1921 execution of a pro-union sheriff, Sid Hatfield, striking miners planned a march to force the lifting of the martial law, free imprisoned miners, and organize the area's workers. Some 10,000 men, armed mostly with whatever guns they could dig out of their closets, assembled to march 50 miles from the town of Marmet, over Blair Mountain, to the courthouse in Logan, rallying, proselytizing, and fighting along the way. They were opposed by the Logan Defenders, a private army of 3,000 under the leadership of anti-union sheriff Don Chafin.

As the miners neared Chafin's three-mile defensive line along Spruce Fork Ridge, open war broke out. Archaeologists estimate that a million rounds were fired over the battle's five days. It is not known how many people were killed, but according to historians, estimates range from 20 to 100, which seems oddly low, considering the number of men involved and the intensity of the fighting. One early newspaper account stated that the miners were loading their dead into boxcars, but said little more about casualties. In early September, federal troops arrived to end the conflict. The state of West Virginia charged the leaders of the strike with treason, and though none were convicted, the trial exhausted the UWMA's coffers and broke the union there until a dozen years later, when the National Industrial Recovery Act officially recognized the right to organize. After that, led by some of the same men from the march, the southern coalfields of West Virginia became a stronghold of union sentiment (at least until more strikebreaking in the 1980s). Union leaders from Appalachia also helped organize other industrial heartlands. "If you work for a living, if you get unemployment, if you have minimum wage or better, paid vacation, or health insurance, you owe it to those folks who stood their ground on Blair Mountain," says Barbara Rasmussen, a historic preservationist and president of Friends of Blair Mountain.

Coal mining has always been a dangerous and difficult job (photos ca. 1920). Prior to unionization in the 1930s, there were few workplace protections for miners.

(Courtesy Kenneth King West Virginia and Regional History Collection | Yale University Art Gallery/Wikimedia Commons)

It was assumed that the physical evidence of the Battle of Blair Mountain had been collected, scattered, or disturbed—an assumption that seemed to be confirmed by a coal industry–funded survey in 1991. Around that time, a history-minded local resident, Kenny King, began exploring the battlefield, collecting artifacts, and teaching himself about archaeology. King's grandfather fought with the miners, and two of his uncles with the defenders. He found widely dispersed sites, showing that the battlefield was larger than anyone had thought, and he began working with historic preservationists to get it listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). However, early efforts stalled because no official archaeological work confirmed

his finds.

In 2006, King helped enlist Harvard Ayers, a professor emeritus at Appalachian State University, to conduct a survey to support a fresh NRHP nomination. They traveled to sites King knew well and searched for new ones. Then they delineated the sites, documented the locations of surface artifacts, and collected representative samples. Fourteen of the 15 sites they examined appeared to be largely intact and undisturbed. In some cases—such as the site with the .32-caliber pistol shells—they found casings together on the ground that weren't found anywhere else nearby, suggesting strongly that they had lain in situ since 1921. "There doesn't seem to have been much disturbance up there, which is totally counter to the folklore that everything had been disturbed," says Ayers.

On the basis of King and Ayers' work, the NRHP listing was approved in March 2009. Just nine months later, however, the battlefield was removed from the list. According to Susan Pierce, director of the West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office (WVSHPO), it was removed because landowner objections had been inadvertently overlooked. Much of the battlefield is owned by Natural Resource Partners, and portions of it are leased for mining by companies including Arch Coal and Alpha Natural Resources. Many of the preservation advocates believe that attorneys representing these companies were responsible for the challenge to the listing. "It was a human error of overlooking objections in an addendum to a document," counters Pierce. "There's no skulduggery." A group including the Sierra Club, Friends of Blair Mountain, the National Trust, and other organizations has since sued the Keeper of the National Register and the Department of the Interior for not following procedure during the complex listing and delisting process. "We're playing a waiting game," says Rasmussen. "The people who want to blow up that mountain are working hard to make it impossible for this to go forward."

(Courtesy Kenneth King)

Though certainly symbolic, the NRHP designation doesn't actually protect anything. What it does mean, however, is that the historic value of a site must be considered in state and federal permitting processes. In this case, the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection and the Army Corps of Engineers would determine whether mining could move forward, or if some form of mitigation, such as a rescue excavation, would be required. Blair Mountain today is considered "eligible to be listed," which, according to the WVSHPO, provides it with the same permit oversight as if the mountain had stayed

on the list.

The coal industry shows no apparent sign that it intends to spare the mountain. According to Robert McClusky of Jackson Kelly, a law firm that represents Natural Resource Partners and other coal companies in the permitting process, the companies still expect there to be some kind of mitigation to honor the history of the site—an excavation, museum, or film, perhaps. In fact, Jackson Kelly has already offered, on behalf of its coal clients with a stake in Blair Mountain, to fund a three-year rescue excavation. Ayers promptly turned the offer down. "They probably would have paid me handsomely," says Ayers. "They do this all the time. Money is no problem for them." Such a plan presupposes that the mountain would eventually be mined, which is not an option for its advocates. "In my mind," says Rasmussen, "blowing up Blair Mountain is just as violent a social action as the Taliban tearing down the Bamiyan Buddhas or [the prospect of] drilling for oil in Gettysburg."

(Courtesy Harvard Ayers)

Opponents of mountaintop removal have suggested that Blair Mountain could be mined with traditional deep mining, which would create more jobs, preserve the landscape, and honor the deep miners who fought there 90 years ago. But according to McClusky, some coal seams—he didn't say those in Blair Mountain specifically—simply can't be mined economically that way. Rasmussen hopes some combination of tax breaks and other incentives might help ease any blow to the industry's bottom line. "We're trying to be very reasonable about it," says Rasmussen. "Now what we're doing is trying to work out a business deal."

The NRHP process brought King and Ayers' efforts to wider attention and led the landowners to post "no trespassing" signs and inform the archaeologists that they can no longer enter the property. Consequently, the only archaeological remains of the battle available for study are the results of the 2006 survey—and they have already begun to rewrite the history of the Battle of Blair Mountain.

Reports from the time of the battle tended to cast the miners as a disorganized rabble with little strategic acumen. Though it was reported that they broke through the defensive line at Crooked Creek Gap, they were portrayed as an unruly mob, saved from annihilation by the arrival of federal troops.

"What we started finding was completely reshaping the narrative of Blair Mountain," says Ayers. It was a transition period in the history of firearms, during the changeover from black powder to smokeless powder, and the miners used whatever arms were available. As a result, the assemblage covers a huge range of manufactured and homemade ammunition—nearly everything available at the time.

(Courtesy Andrea Lai)

Ayers has collaborated with and turned over the ongoing analysis to Brandon Nida, a young archaeologist from southern West Virginia and a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley. Nida and Ayers conducted statistical analyses of the ammunition to distinguish miner sites—those with a diverse range of shells—from defender sites, where there is more consistency. At one site, a mile northwest of Crooked Creek Gap, an unusual concentration of spent bullets from both sides of the conflict is evidence of close-quarters fighting. "You kind of come to the conclusion that the attacking miners were putting the heat on [the defenders]," says Ayers. The proximity of this site to Crooked Creek Gap, where the defensive line was broken, suggests the miners had advanced far, and were attempting a pincer movement to outflank the defenders. Other sites show the miners were coming up five or six hollows or creeks at once, tactical details that aren't documented anywhere else. It is possible they were far more coordinated and successful than previously thought. "It would be an archaeologist's dream to be able to go up there with all this good preservation," says Ayers. "You could learn so much about the strategic aspects, the much more sophisticated approach the miners had, in terms of coming at [the defenders] from multiple directions."

Nida is both continuing the effort to reconstruct the events of the battle and its social context, and placing himself at the center of the movement to protest the mining of Blair Mountain and mountaintop removal in general. He's analyzing bullets, reconstructing sight lines (an effort complicated by the variety of the bullets and 90 years of forest growth), and seeking evidence of the strikers' tent colonies. He's also started an excavation at the Whipple Store, a fortresslike company store, that will help flesh out the miners' casus belli. All of his work comes in the context of a community-based, activist approach to archaeology. Nida interacts with locals to understand their relationship to the past and uses archaeology as a tool to fortify the mountaintop removal protest movement. He is also hatching more traditional activist plans, such as organizing protests and establishing a community center in the town of Blair.

(Courtesy Kenneth King)

In the United States, there's a history of using archaeology in grassroots activism. At Blair Mountain, the two can seem inextricable, even as the activism sometimes appears to hamper archaeological research. "One of the problems we have now is that so much of our time and energy is built around preserving the mountain and making sure that it's not blasted, that the capacity isn't there for doing a lot of in-depth research," says Nida. "Am I going to analyze bullets or go to this permit hearing?"

It's a Monday morning in June, and Nida is standing on a baseball diamond in the town of Marmet, before a crowd of about a hundred people and a bank of cameras.

"We are Appalachia! We're all getting pushed around, we're all getting our rights stepped on. It doesn't matter if you're a union member or an environmentalist! We're united in a common cause," he shouts into a microphone. "Our history is the deep-rooted history! We're the people, and we're rising up!" Nida pounds his fist on his chest before he lifts it over his head. Shutters click in a chorus.

Nida is one of the leaders of a 50-mile protest march following the route from Marmet to Blair that the miners took in 1921. As the march proceeds, two-by-two along the narrow edge of twisting, sloping Route 94, one car honks in support and the next guns its engine in derision. "It takes a lot of water to turn a ship," Nida says.

(Samir S. Patel)

The work at Blair Mountain and Nida's other activities have their most direct antecedent in the study of the site of the Ludlow Massacre in southern Colorado. There, Randall McGuire of Binghamton University and Dean Saitta of the University of Denver ("Letter from Colorado," November/December 2004), studied a 1913–1914 coal mining labor conflict in which strikebreakers fired into a tent camp, leading to the deaths of 11 women and children. McGuire and Saitta excavated there, took exhibits of artifacts to union halls and rallies, and published articles on their research in union publications. Among the project's goals was to present findings to working-class people, often thought to be left out of the conversation surrounding archaeology, to strengthen labor solidarity and inform the wider public about the period in history and its importance. "You are very forcefully showing that [rights] weren't just given to workers, but that workers won these things through struggle and enormous sacrifice," says McGuire.

Following that model, Nida has also begun to present his findings to the working class, such as at an event for the UMWA Local 1440 in Matewan, southwest of Blair. He's also been using the archaeology of Blair Mountain as both icebreaker and weapon, in direct service to his political goals, which are built around the idea that the coal industry and mountaintop removal in particular continue to displace, oppress, and sicken the people of Appalachia. The archaeology helped bring the Sierra Club, National Trust, and UMWA to the same table. At the rally in Blair that closed the June march, Nida even showed some of the artifacts to one of the bosses of a nearby mountaintop removal mine run by Arch Coal. The surface miner was particularly interested in a 1918 bullet. "It just kind of opened up dialogue," Nida says. "It takes archaeology out of the institution, and I think archaeology benefits from being in as many diverse places as it can be."

(Samir S. Patel)

Such an approach to activism through archaeology is open to the criticism that Nida's personal investment in the cause might compromise archaeological conclusions. "The issue is not whether we politicize it," says McGuire. "The issue is whether we confront the political nature of what we're doing, are explicit about it, and are self-critical about it." For archaeologists such as McGuire and Nida, all archaeology is inherently political. And when that subtext goes unrecognized and unexamined, it can have pernicious effects for the people who are stakeholders in that history. For example, Nida says that the privately conducted 1991 survey that found little archaeological evidence on Blair Mountain was paid for and influenced by an eager coal industry, even though it was conducted with a mantle of objectivity.

"There's a whole power structure there built around what they call objective archaeology and it's killing my people, it's killing the mountains, and it's killing my culture," Nida says. "So for me, the idea that what I'm doing is activist and what they're doing is objective is absolutely ludicrous."

The Second Battle of Blair Mountain has taken a personal, emotional tone, audible in every voice. West Virginians, and Appalachians in general, are often subject to stereotypes that cast them as culturally deficient, isolated from American society by ignorance, feuds, and fear. The jokes leave scars as deep as those of mountaintop removal. To learn, through archaeology, that the miners were not lawless, but fought with justification and skill—and that they may have been winning—is a matter of personal and regional pride. The mountain itself has come to represent some sense of Appalachian self-worth, separate from the industry that has dominated the region's modern history. Reasserting a claim to that past is what Nida means when he speaks about "rising up."