How people dress and adorn themselves has long been a primary way of showcasing their identity and communicating it to others. The ancient Maya, whose world was one of vivid cultural practices and strict hierarchy, with rulers playing an essential role mediating between the gods and mere mortals, developed a deep interest in status and display. One of the ways this manifested itself was in their rich array of clothing and personal ornamentation. “For the Classic Maya, in many ways, clothing defined personhood,” says Alyce de Carteret, a fellow in Art of the Ancient Americas at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Numerous aspects of an individual’s identity—from their political position, to their trade, to their gender—were communicated through adornment, and depictions of clothed bodies encode this vital information. To study ancient Maya dress, then, is to study ancient Maya society itself.”

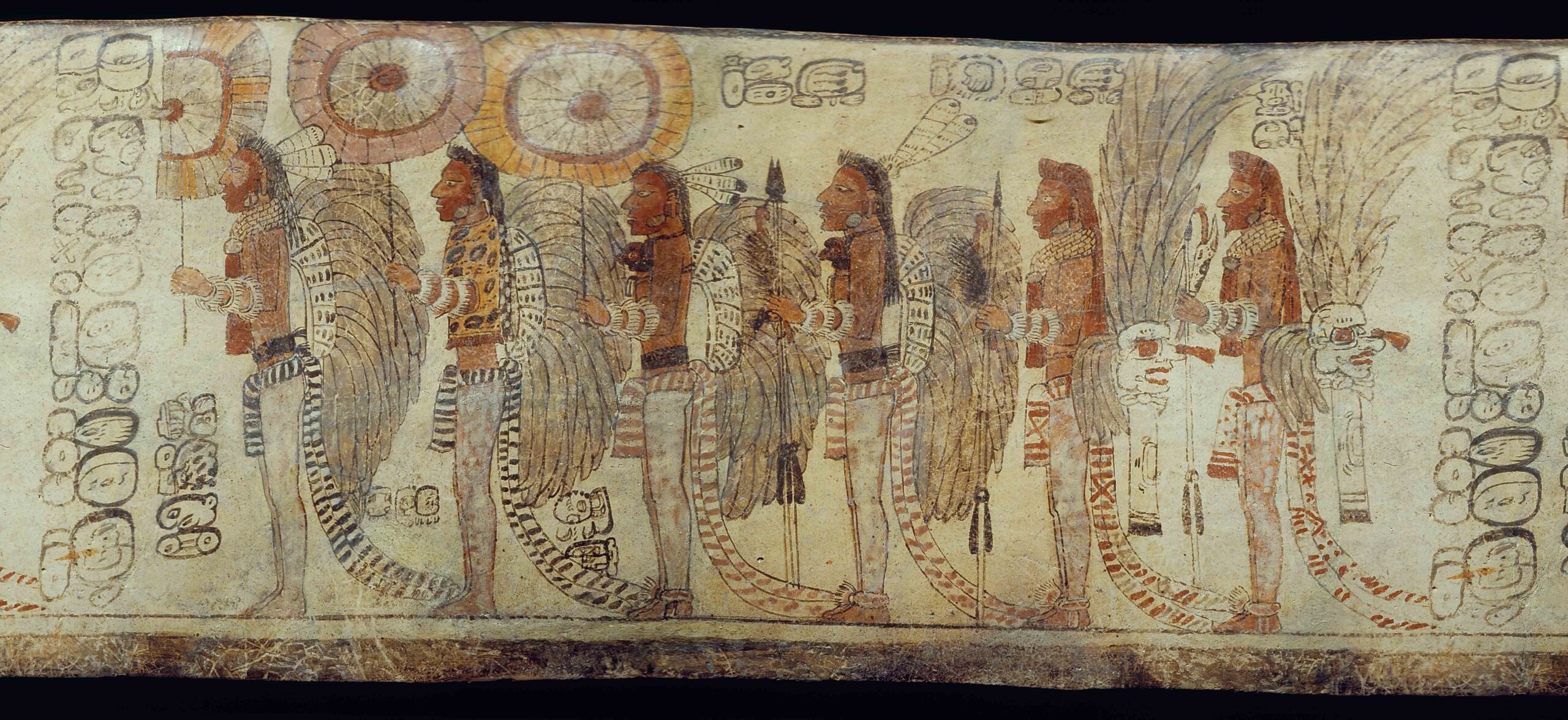

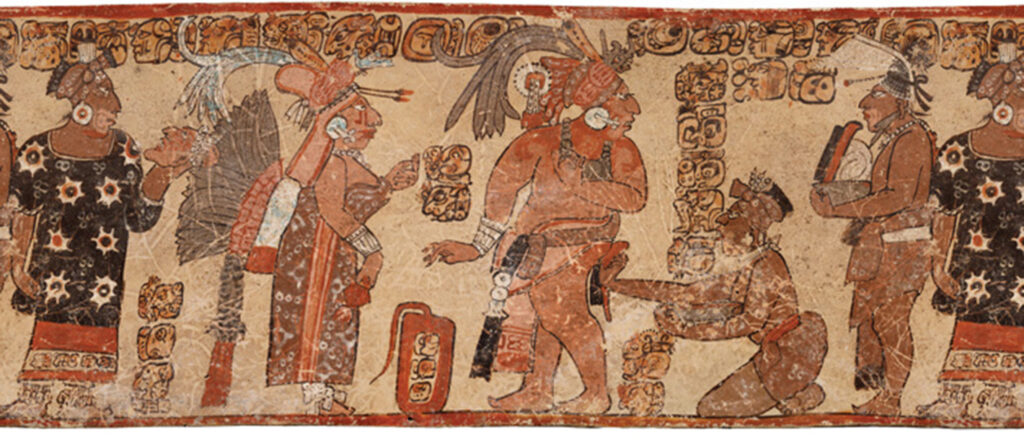

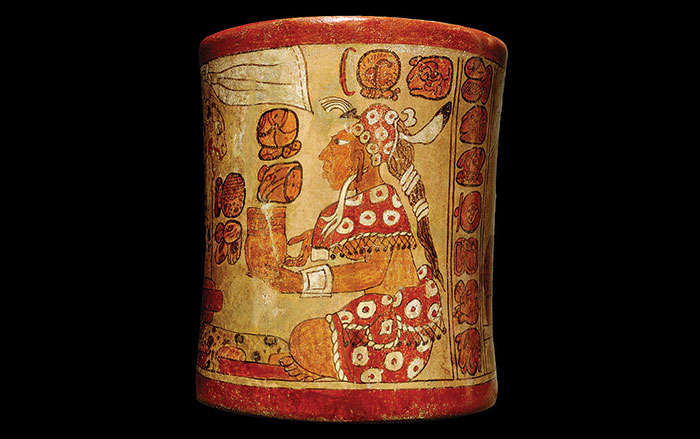

By the second millennium B.C., the Maya occupied much of southern and eastern Mesoamerica, including all of the Yucatan Peninsula, Belize, and Guatemala, as well as western Honduras and El Salvador and parts of the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas. Their world was not a unified empire, but rather a collection of kingdoms based in cities such as Copan, Palenque, and Chichen Itza. At various times, new power centers emerged, and their leaders pursued ambitious architectural projects whose remains still impress today, while older centers declined. Much of the scholarship on ancient Maya clothing and adornment focuses on the Classic period (A.D. 250–900), when the Maya population grew dramatically, and royal courts, with their flamboyant ritual displays, became more prominent. While few items of clothing and ornamentation have been preserved in the archaeological record, scholars use depictions on painted murals, ceramic vessels, stone stelas, and clay figurines dating to this period to learn what the ancient Maya wore.

Many of these images show the Maya engaging in or preparing for religious ceremonies, which were scheduled based on an extremely complex calendar system and called for specialized clothing and accessories, from elaborate headdresses to ornate sandals, and even patterns painted directly on the skin. Other images portray warriors or ballplayers, who often integrated animals into their outfits. Still others depict resplendently costumed rulers towering over naked captives. Maya adornment incorporated a broad range of materials, from the luxurious blue-green feathers of the quetzal bird to the spotted skin of the jaguar, which was sometimes worn as a cape with head and paws still attached. Even a seemingly mundane substance such as paper made from bark, when crafted into a simple headband, played a key role in one of the most important Maya rituals of all. And when fashioned into earrings, this paper helped facilitate the Maya ceremonial practice of self-sacrifice. “All these examples point to something deeper and more complex than the material culture of clothing alone can convey,” says Astrid Runggaldier, an archaeologist and assistant director of the Mesoamerican Center at the University of Texas at Austin. “They hint at the role of attire as accoutrement to the social roles embodied by human beings.”

-

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Headdresses

(Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art)

(Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art) -

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Nasal Prostheses

(Bridgeman Images)

(Bridgeman Images) -

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Capes and Cloaks

(Courtesy Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pa.)

(Courtesy Penn Museum, Philadelphia, Pa.) -

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Body Art

(Photo credit: HIP / Art Resource, NY)

(Photo credit: HIP / Art Resource, NY) -

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Sandals

(G. Dagli Orti /De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images)

(G. Dagli Orti /De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images) -

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World July/August 2020

Earrings

(HIP / Art Resource, NY)

(HIP / Art Resource, NY)