Sometimes it takes a village to raise a window. Between 2015 and 2017, skilled masons meticulously carved and beveled arches and four-lobed flourishes for a Gothic-style stone window frame in Guédelon Castle’s ornate Chapel Tower. All that remained was to install some glass. But there was a problem, and the carpenters, painters, blacksmiths, basket weavers, historians, and archaeologists who work on-site were all enlisted to figure it out. Eight years later, the matter of what to put in the window of a medieval castle has nearly been resolved…maybe.

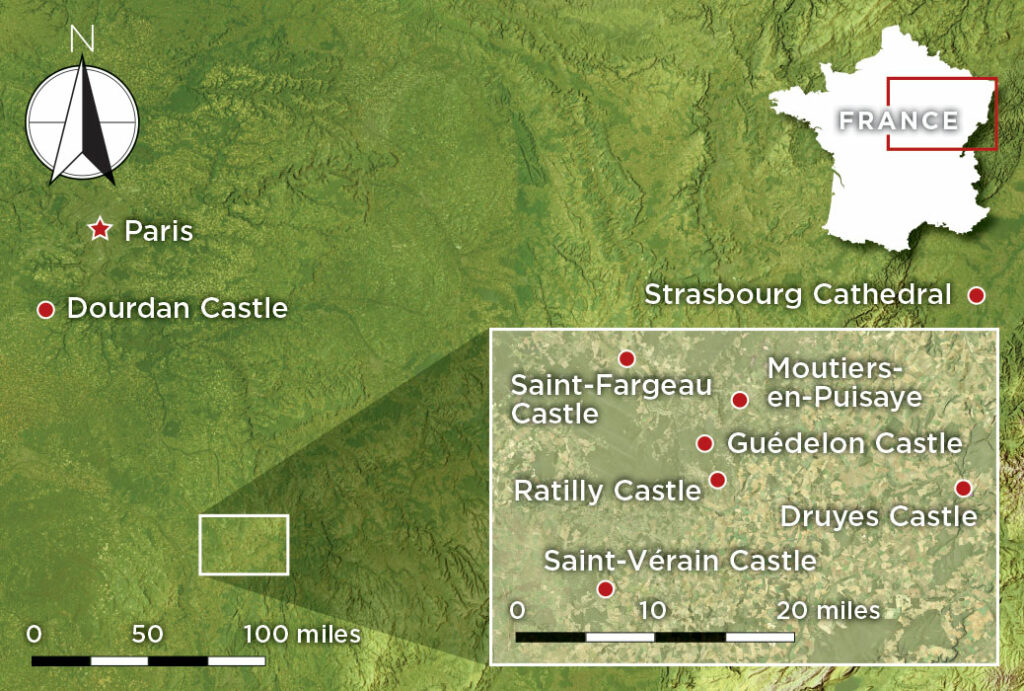

Luckily, the team of 40 professional builders and craftspeople at Guédelon Castle love a conundrum. The castle, located in an abandoned quarry in the Puisaye region of Burgundy, 100 miles southeast of Paris, is the site of one of the world’s most comprehensive and longest-running experimental archaeology projects. In this kind of undertaking, archaeologists partner with skilled laborers to test hypotheses about how people worked, lived, and built in the past, filling gaps in academic knowledge through real-world trials. The project launched in 1998 with a straightforward mandate: Build a thirteenth-century castle using only thirteenth-century tools, techniques, and materials. Medieval archaeologists would provide guidance. And the hope was that every obstacle would reveal something that historians, architectural researchers, archaeologists, and castellologues, or scholars who specialize in studying castles, didn’t know. “At Guédelon, we’re looking for what disappeared in traditional archaeology,” says Florian Renucci, the master mason and longtime site director at Guédelon, who was formerly a researcher at Sorbonne University. “Experimental archaeology means bringing to life what workers can do. We’re always looking, hearing, feeling. Now, with our work, the castle can speak.”

The first thing the castle said about windows is that they couldn’t have been made of glass. Guédelon’s artisans and committee of scientific advisers are constantly scouring medieval texts for clues about how thirteenth-century builders would have handled such details. In the castle’s imagined backstory, the fictitious seigneur, or lord, of Guédelon was a cash-conscious minor noble trying to make a home in 1228, putting him—and today’s builders of Guédelon—at the mercy of his financial circumstances. In that era, glass was extraordinarily expensive and reserved for places of worship and royal residences. Glasswork, the team learned, swallowed up half the cost of building a cathedral. Unfortunately, whatever material was used to fill the window frames of lesser edifices has left no traces in the archaeological record.

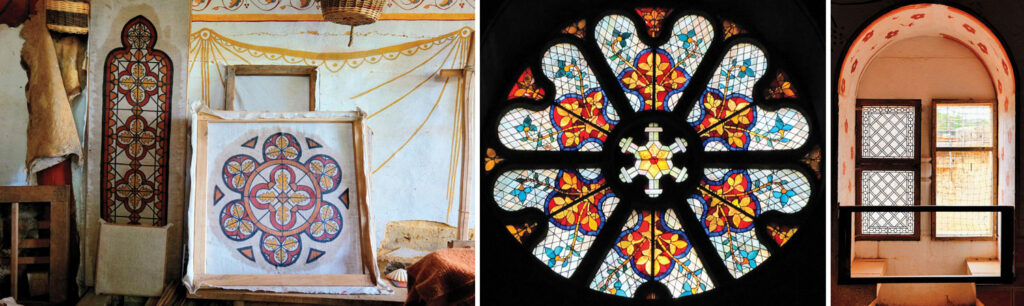

Artisans, many wearing period garb, initially tried to fashion goatskin panels for the Chapel Tower window after learning that this material had been used in contemporaneous buildings—but the panels warped in the winter frost and cracked in the summer heat. The team then reviewed a list of prices for the materials used to build the Palais des Papes, or Palace of Popes, in Avignon, which was begun in 1252. They learned that humble linen, stiffened with beeswax, once covered some windows at this grandest of châteaus. Valérie Lachény, Guédelon’s master painter, decorated linen canvases with an eye-catching design of golden oak leaves ensconced in maroon semicircles—a pattern inspired by twelfth-century stained glass at Strasbourg Cathedral in northeastern France. In spring 2025, three painted linen panels could be found propped in her workshop, each waiting to be affixed between wooden frames engineered by the castle’s carpentry atelier to fit into the tower’s stone window molds. Each frame takes 150 hours to join, rasp, carve, and assemble.

Meanwhile, an ongoing debate about how to fasten the linen to the frames rages. Guédelon’s blacksmiths have forged bespoke iron tacks, but, as carpenter Simon Malier explains, this option for attaching the fabric requires finesse, lest the wood crack. The basket weavers have suggested sewing the linen into the frames with a cow-horn needle. “For this kind of thing,” Malier says, “it’s a team effort.” Whatever method wins out, when the window is finally mounted, the waxed linen exterior will be brushed with flaxseed oil to protect it—which may or may not work. Recently, Malier says that he, Renucci, and Lachény stumbled on a snippet of medieval text describing a tantalizing linen window coating that shines “like crystal.” “But we don’t have the bloody recipe!” he laments.

“Because the Guédelon team works in the conditions of thirteenth-century laborers, they discover techniques that people were figuring out at that time,” says archaeologist and Guédelon project scientific committee member Nicolas Faucherre of Aix-Marseille University. “That’s why Guédelon is so important for archaeologists.” Every detail must be considered, and there are no shortcuts. The site is an unparalleled experimental archaeology project and may remain never-quite-finished forever. By observing the work of the castle’s “medieval” builders, archaeologists and other scholars have discarded old ideas and hatched new ones about how monuments of the era were created. They have solved mysteries about how ceramic for tiles was mixed and fired, how lime mortar was troweled to hold structures fast and make them last, and how scaffolding was erected to reach dizzying heights. Some discoveries may seem esoteric, but each one can help refine scholars’ understanding of tens—or even thousands—of medieval sites.

In 1995, Faucherre and archaeologist Christian Corvisier found something quite striking while studying Saint-Fargeau Castle, 5.5 miles northwest of Guédelon. The château there was built from the fifteenth through the seventeenth century, but the archaeologists discerned the foundations of a smaller, earlier fortification with thirteenth-century characteristics beneath it. The château’s owner, Michel Guyot, became intrigued by the prospect of rebuilding the earlier structure. So, he bought the disused quarry in Guédelon Forest in the commune of Treigny and embarked on the adventure with cofounder Maryline Martin, a young businessperson. Instead of imitating Saint-Fargeau Castle, they decided, the new structure would be an original, loosely following the model of Ratilly Castle, which had been built around 1270 just two miles south.

“When I came here for the first time, it was just forest,” says Martin, who is now the owner of Guédelon. “But we had a lot of luck.” The forest, 370 acres of which belong to Guédelon, has ample oak for timber, a lode of iron-streaked sandstone that serves most of the masons’ and blacksmiths’ needs, and seemingly bottomless pockets of colorful minerals for the painters to extract pigments from. “It’s incredible for me to imagine how many solutions we have just within sight,” Martin says.

The first years at Guédelon were strenuous and invigorating, long days testified in chisel marks on stone, ax splits on timber, and strokes on sketch pads. It took three years to build the 11.5-foot-thick foundation walls, which trace a perimeter of 660 feet. Many of the original laborers were unemployed, some with past legal difficulties, and had been left behind in a place where most factories and quarries had shuttered, and even the railroad had ceased running long before. As Martin recalls, quarriers would etch their encouragement on blocks passed to the masons. “Only ten to go! Only nine to go!” read inscriptions on some stones. In 1998, the construction site opened to curious visitors, and 300,000 now come each year, 60,000 of whom are schoolchildren. The castle, and everything else Guédelon includes, encompasses a self-sustaining business, funded by ticket sales, an on-site restaurant, and a gift shop.

Amid innumerable false starts and experiments gone awry, Guédelon Castle began to rise. Between 2000 and 2017, Renucci and his team executed four different styles of medieval ceiling vault—mostly to see if they could—all without any ahistorical reinforcement from iron or concrete. By 2010, the carpenters had lifted magnificent timber trusses over the castle’s Great Hall and living quarters, and soon Guédelon’s grounds included gardens, stables, a water mill, and 10 workshops.

The Puisaye skies threaten rain, as they often do in April, but excitement is in the air. Guédelon opened for the season just a few weeks ago. Stonemasons have completed two of the castle’s four corner towers using the area’s brilliant burnt-orange sandstone. The table is set in the Great Hall under a lofty oak-timber barrel vault. Painters have adorned the hall’s antechamber with willowy vines and cheery flowers dancing around stone blocks. The carpenters have even mounted a linen window there—it seems to be faring well thus far. Beyond the castle walls, a blond-maned horse makes light work of pulling an empty cart, and kids stop to gawk at the “squirrel cage,” a leviathan treadmill winch atop the south curtain wall. Inside this human hamster wheel, masons trudge in pairs to power a pulley that lifts blocks and mortar up to the parapet they’re finishing.

Renucci is at the castle this morning as usual, but there’s no such thing as an ordinary day for the master mason. He has to sketch and resketch all plans by hand, troubleshoot glitches with archaeologists around the country, convene weekly meetings of artisans to hear their latest updates and bon mots, and oversee all construction and craft operations. Renucci, who helped restore Paris’ iconic sixteenth-century bridge, the Pont Neuf, first donned a period-appropriate tunic and capelet for his role at Guédelon in 1998. Today, the clanking of the quarriers and the whoosh of the forge bellows tell him the morning has begun smoothly, so he’ll take a lap around the castle to check on progress.

He strides out from the burly two-tower main gatehouse and scrambles down to the exterior foundations of the Chapel Tower. With his measuring stick—articulated in both modern centimeters and the inches and feet thirteenth-century masons used, which are almost identical to today’s—Renucci gestures at a section of Guédelon’s very first wall. The stone blocks here are precisely fitted and smoothly dressed, a visible contrast with the rest of the walls’ masonry. It looks as though stoneworkers had begun building a different castle entirely. “When we started, we tried to make the stones very uniform, very planned, because we learned at masonry school that this is a better way,” Renucci says. But each stone took two days to cut and dress. In the thirteenth century, masons usually collected their fees in weeks worked, not stones cut. Could the budget-conscious seigneur of Guédelon really have afforded this? Did he have time to wait for a roof over his head and walls to protect his family?

As he has done countless times over his Guédelon career, Renucci looked to France’s wealth of medieval archaeology. In its imagined story, Guédelon was founded just after the rule of Philip II (reigned 1180–1223), the first ruler to style himself king of France. Philip doggedly expanded the throne’s domain to include most of the area under the French flag today, in part through a campaign of building defensive fortifications in a signature Philippian style that his vassals mimicked. Around 100 such fortresses survive in France, a primary reason that 1228 was the date chosen to establish Guédelon. One Philippian castle stands largely unmodified in Dourdan, just southwest of Paris, and “predates” Guédelon by just a few years. The walls of Dourdan Castle, Renucci noticed, were faced with irregular, roughly dressed blocks, inspiring him to alter his course. “When we changed methods, we were able to make four stones in one day,” he says. “Our mindset today is to take your iPhone and say, ‘Can I order wood or stone in 20 hours?’ The primary challenge of building Guédelon is to forget the twenty-first century.”

Renucci heads back into the castle, climbs a spiral staircase, and follows the wall-walk to the stonemasons’ pièce de résistance for 2025, the upper level of the gatehouse. Above the gate, masons and carpenters will soon add an arch, a lintel, a portcullis, and a “murder hole”—a maw through which defenders could throw rocks and pour hot pitch on marauders. The design of the 2,000-pound portcullis is an educated guess; there are no working thirteenth-century originals left. Faucherre, who is studying the medieval Louvre Castle in Paris and the Aigues-Mortes ramparts in the south of France for inspriation, was flummoxed by the question of how a portcullis counterweight mechanism would have functioned at these sites. But his conversations with the Guédelon team this year have helped him envision the machines. “We can never be sure,” Faucherre says, “but now we are obliged to make a portcullis that can move.”

The murder hole will remain purely ornamental. “This is a very pacifist castle,” laughs stonemason Yaniv Gammeter. “Very anti-violence here.” In truth, local Guédelon-size Philippian castles such as those at Ratilly, Druyes, and Saint-Vérain weren’t equipped for serious warfare. “You can view these castles as a type of very large manor house,” Gammeter says. “They’re symbols of power but weren’t meant to survive a siege.”

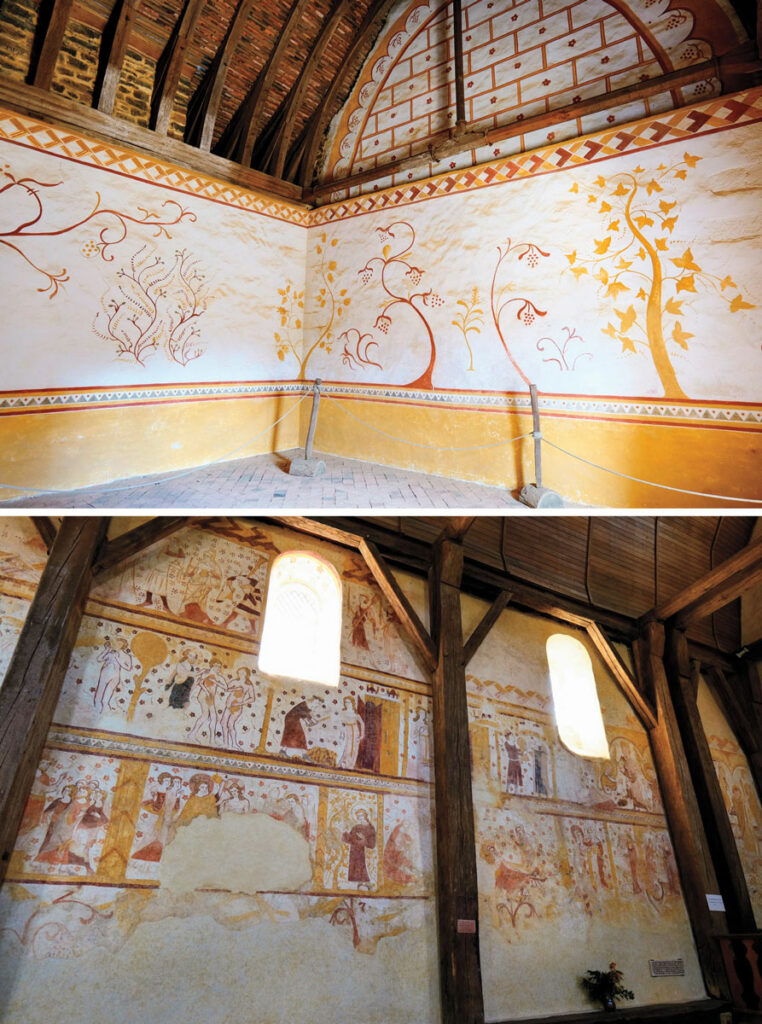

As Guédelon has grown, so have the possibilities. Why stop at a castle? In the thirteenth century, people here would have painted, prayed, farmed, milled flour, fell ill, recovered, and listened to the leaves and birds to get the day’s weather report. Vanishingly little evidence of those activities can be found by excavating, and thus the artisans and researchers at Guédelon have to get creative. Lachény, the painter, has concocted no fewer than 17 pigments from local ores and plant material, some of which she’s found in the forest herself. While retrieving a bowl of fine dark ocher powder from her oven, she explains that glands on cherry tree leaves, when crushed, boiled, and made into paste, produce a reddish-black hue. In their atelier, the painters glide around color-spattered stacks of mixing bowls, shelves of ceramics, swatches of linen, and trays of yellow, pink, gray, and blue powders. New colors occasionally arrive unannounced. “Sometimes a quarryman cleaving stones comes over saying, ‘I found this,’” says Lachény, who investigates whether the discovery can be useful for her work or for some other endeavor in the castle.

Twelfth- and thirteenth-century wall paintings rarely survive, but some of the most intact examples in France can be found in the Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Moutiers-en-Puisaye, just two miles from Guédelon. Around images of angels, saints, and Adam and Eve, medieval masters enlivened the walls with bright orange flowers, slate-blue stars, and unruly golden vines, motifs that inspired Lachény’s decoration of the Great Hall’s antechamber. “It’s got plenty of spirit, it’s joyful,” she says. “We talk about Dark Ages, but the Middle Ages were really colorful.”

The Middle Ages were also noisy, and sound has proven crucial to the successful construction of a thirteenth-century water mill, one of Guédelon’s more daunting experiments. In 2008, a rescue excavation turned up two medieval mills in eastern France near the village of Thervay. An exceptional trove of 200 wood fragments was preserved from one mill. Using these fragments as their guide, Guédelon’s carpenters spent two years fabricating their own mill. It croaked and creaked, but nevertheless, the millstones barely budged. The miller, Constantin Lemesle, decided to let it run until wood started snapping. “If we don’t make mistakes, we can’t understand the machine,” he says. With a working design on the first try, the mill would have produced plenty of flour but no knowledge. Finally, Lemesle says, the mill is singing.

In the past decade, as Guédelon has evolved with endeavors such as the mill, more scientists have come to see and hear all the commotion. Mylène Pardoën, a soundscape archaeologist at the Center of Social Sciences and Humanities, Lyon Saint-Étienne, has visited Guédelon 23 times since 2020 with her arsenal of microphones, which she pokes into the millstones, the cracking quarry slabs, and the fires of the forge. “The thirteenth century sounds different, and every material transmits information,” she says. In 2023, relying almost entirely on data collected at Guédelon, Pardoën composed a four-minute surround-sound reconstruction of the building site of Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral circa 1170.

After 11 years of repeatedly fixing Guédelon’s finicky grain-crunching contraption, Lemesle can imagine the whole medieval community’s relationship to the mill. The seigneur collected taxes in the spring for its operation. Peasants in the fiefdom could bake or buy abundant, nutrient-rich bread, leaving time to raise animals and plant crops, an investment toward an energetic summer dedicated to working the fields. In years when the skies failed to provide rain, flour would have to be milled by animal or manual labor, and there’d be fewer hands to, say, build a castle.

How groups and systems functioned or fell apart in the Middle Ages is what the work at Guédelon illuminates above all else for archaeologists. “We’re putting pieces into a big puzzle,” says archaeologist Anne Baud of Lumière University Lyon 2, director of excavations at Cluny Abbey in east-central France. This abbey was enormous, its twelfth-century basilica’s vaults rising nearly 100 feet—then the highest in Western Europe. Nothing like it had ever been built. “You would think there must have been hundreds and hundreds of builders who were working there,” says Baud. “But is that true?” At Guédelon, she and other archaeologists have observed that medieval labor was likely leaner, more collaborative, and more synchronized than accounts of the time suggest. “The empirical knowledge we gain,” Baud says, “is linked to Guédelon’s laborers’ experience.”

The Guédelon project and its artisans have begun to make their mark on restoration efforts across France. When Notre Dame Cathedral burned in 2019, the team was summoned for their highest-profile contribution. (See “Exploring Notre Dame’s Hidden Past.”) Renucci, along with six of Guédelon’s carpenters, set off to help rebuild the Forest, the immense timber framework of the cathedral’s roof. Conventional wisdom held that clear-cutting and drying centuries-old oaks would be required to replicate the original structure. But the Guédelon carpenters knew better. They’d built a formidable oak trusswork for Guédelon’s Great Hall several years earlier, learning that smaller, younger oaks, freshly cut and green with moisture, were more pliable. The crew brought along 60 custom-fitted medieval axes, forged at their castle, to equip the Forest’s carpenters. “I’m very proud of this,” says Martin, Guédelon’s proprietor. “It’s necessary to have dreams together.”

No one expects the Guédelon reverie to end any time soon. Baud and Renucci are now hashing out plans for a Guédelon church in the forthcoming Guédelon village, which is still on the drawing board. On a sunny afternoon, Renucci stops by Ratilly Castle for ideas. He traces the courses of stone, pulls weeds from cracks in the mortar, and inspects long-ago quarrier’s marks and scaffolding holes. He starts to forget the twenty-first century, his mind on gates and portcullises and spectral guards heaving them open and clanging them shut. The castle’s centuries-old knotty oak door, heavy with a mess of iron bolts and locks, catches his eye. “Very interesting, this kind of system,” Renucci muses, snapping a photo of an entryway he has walked through dozens of times. “You come for stone, and you notice wood. That’s the magic thing about a castle.”

Slideshow: Building the Last Medieval Castle

Philip II, the first ruler to style himself king of France, reigned from 1180 to 1223, but some of the 100 or so surviving French castles designed in the Philippian style postdate the king’s death by decades. In fact, work on the newest example of the style, Guédelon Castle, began in 1998. In the quarter-century since construction started in the forested Puisaye region of Burgundy, Guédelon has become one of the world’s most comprehensive and longest-running experimental archaeology projects. Everything done on site, from mixing lime mortar to cutting timber beams to weaving baskets, uses only thirteenth-century tools, techniques, and materials. Guédelon’s 40 stonemasons, woodcutters, weavers, painters, blacksmiths, and other artisans draw inspiration from contemporaneous sites and texts. Each obstacle they encounter is an opportunity to solve a problem, medieval-style, and to fill a gap in archaeologists’ knowledge of the era.

Video: Blacksmiths at Work

Blacksmiths Caroline Hasne and Mathis Lacroix forge a tool for making nails. Hasne, a new employee in a very old job, likes the work so far. “I love to try to re-create some old techniques that we don’t see anymore by studying old objects,” she says. “And I’m paid to do it!” (Credit: Ben O’Donnell)

Video: Guédelon’s Mighty Mill

The water mill in Guédelon Forest comes to life each spring, weather permitting. Its design follows a medieval mill found in 2008 in the village of Thervay, 160 miles east of Guédelon. That machine was only preserved in fragments of wood, and no one knew how such a thing would run in practice. In the first years of the Guédelon mill’s operation, the upright wooden cogs on the small horizontal gear proved brittle. They were replaced with ones notched along the grooves of the wood. Pig-fat grease was swapped out for cow fat. Spring brought the right amount of rain. Et voilà! (Credit: Ben O’Donnell)

Video: A Weaver’s Craft

Today, baskets are for picnics and the Easter Bunny, but in the Middle Ages, they were all-purpose containers, used for collecting and storing crops and food, or for transporting construction tools and materials. Like the blacksmith, the basket weaver touches practically every part of the castle and community in some way. (Credit: Ben O’Donnell)