Nothing but a forest of bleak sided chimneys and walls of brick houses tottering and cooling in the wind...a more desolate site cannot be imagined than Hampton today. —Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1861

Along the Hampton, Virginia, waterfront, the Virginia Air and Space Center, a vaulting modern structure, evokes a bird taking flight over the Hampton River. Like everything else in Hampton’s downtown, the building rests upon the ruins of a city deliberately put to the torch in 1861. At that time, the city’s Confederate-aligned inhabitants were anxious about Union control of nearby Fort Monroe and even more so about an influx of African Americans to the fort. In August of that year, the white population of Hampton evacuated, and the Confederate army destroyed the city.

The African-American population that had the people of Hampton on edge was mostly runaway slaves who had arrived at Fort Monroe seeking Union protection. Fort Monroe sits on a small peninsula at the southern end of the city, overlooking the broad waterway known as Hampton Roads. In the summer of 1861, it would have made a critical destination, just beyond Confederate reach, for runaway slaves. By law—the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850—runaway slaves were to be returned to their owners. But instead they found freedom at Fort Monroe, thanks to a commanding officer experienced in exploiting legal loopholes.

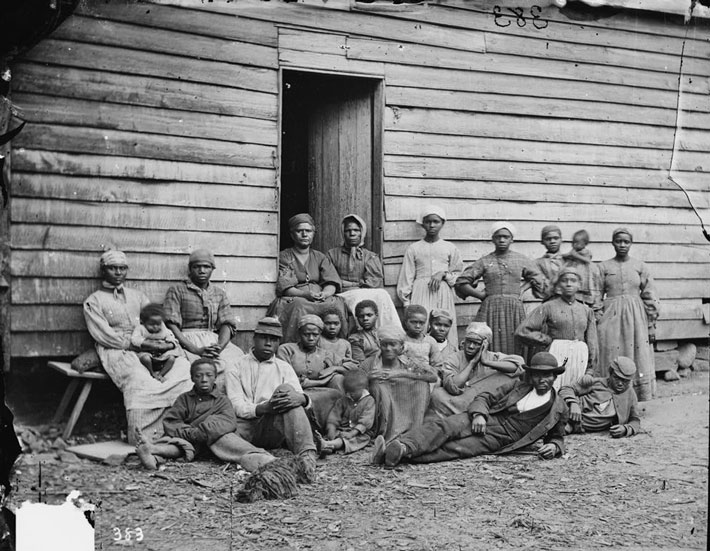

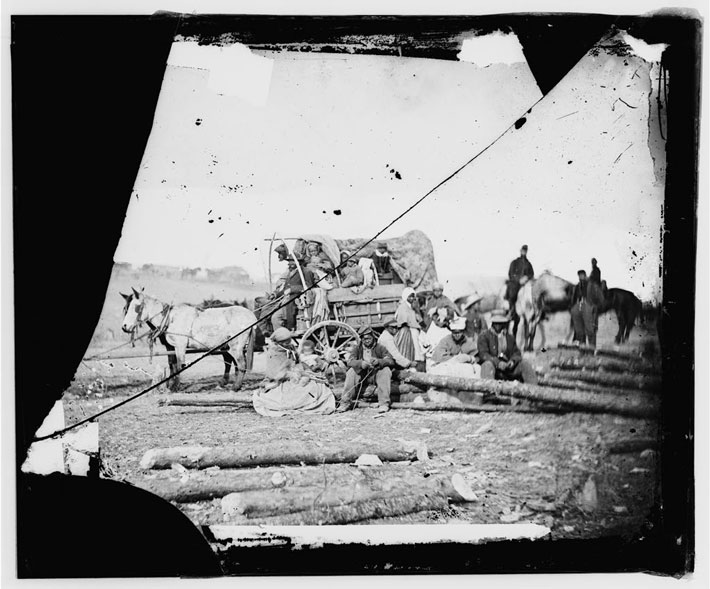

Once the Hampton residents fled, wide areas were left open for settlement by these newly freed people. Soon, empty fields next to the charred city developed into an independent community supported by the Union army. Word of the freedom and autonomy of the camp spread, and more such settlements arose near Union strongholds, sheltering runaways, providing labor for the Union army, and beginning a quiet revolution.

Today, on city-owned land just off Armistead Avenue, sits the site of the original community—once known as the Grand Contraband Camp—that the former slaves established next to, and eventually within, Hampton. The recent demolition of dilapidated apartments there has cleared the way for an investigation into the site’s history. The James River Institute for Archaeology, with funding from the city of Hampton, is conducting the first excavations. Archaeologists hope to learn more about the lives of the newly freed, including how they constructed their homes, how they cooked, what they ate, and what their daily routines might have been. The work is an exploration of the beginnings of one of the first self-contained African-American communities in the United States, a community that began in part because three slaves had refused to be separated from their families to build Confederate fortifications.

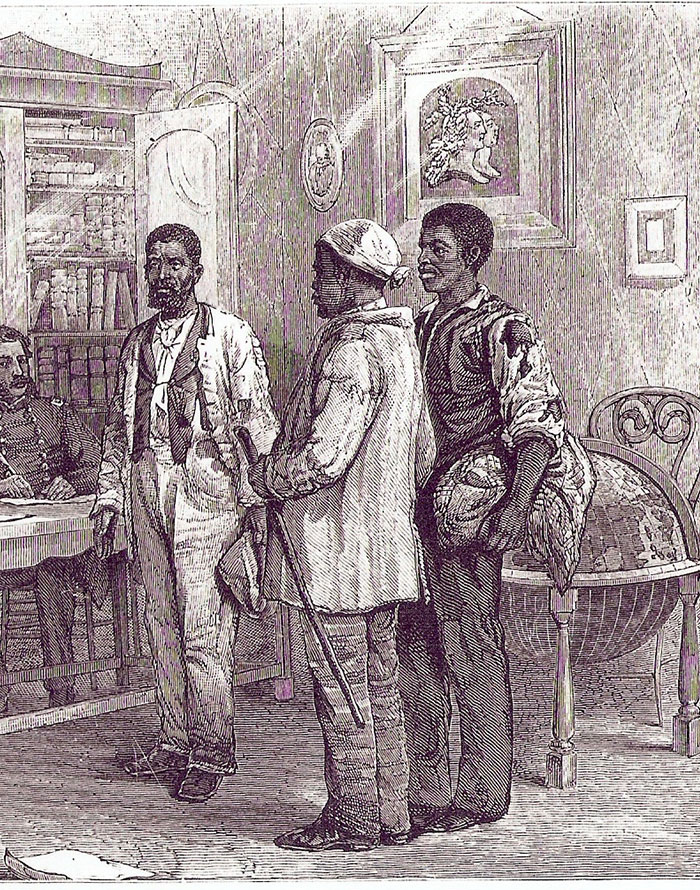

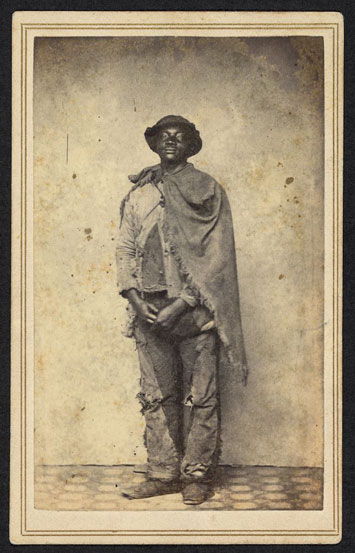

Prior to the Civil War, there were limited routes to freedom for enslaved African Americans. Some bought freedom or were granted manumission, or formal emancipation, after the death of an owner. But for most, including Frank Baker, James Townsend, and Shepard Mallory, risky escape was the only option, with failure sure to bring brutal punishment. The three men, listed as property in an overseer’s notebook, had been sent to Sewell’s Point near Norfolk to build a battery for Confederate artillery. Their owner then planned to move them to North Carolina, far from their families, to construct more rebel fortifications. So they fled to Fort Monroe, the largest U.S. military outpost or fort at the time. Even if their escape attempt were successful, the men had slim hope of freedom: Helping a runaway meant a fine, prison, or both, and a bounty could be paid for their return.

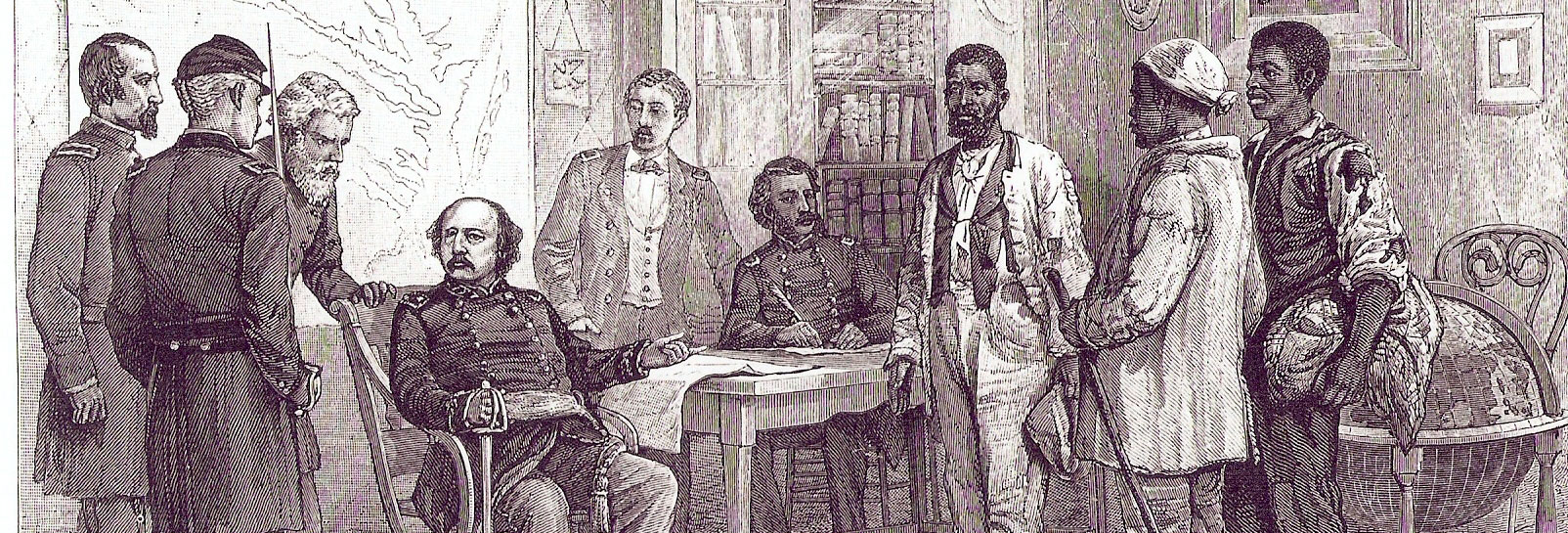

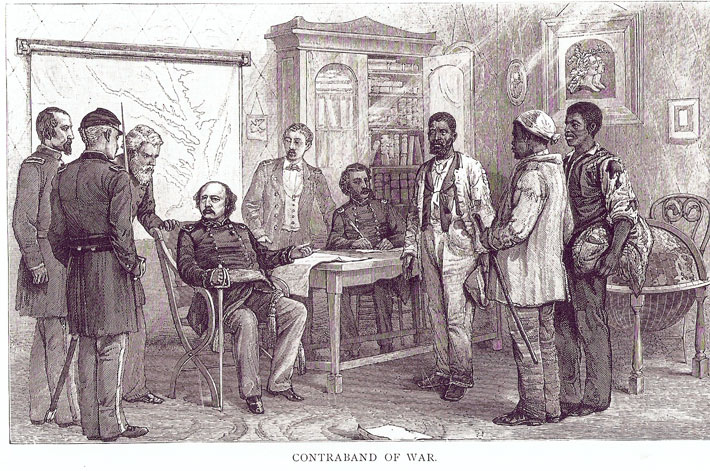

In command at Fort Monroe was Major General Benjamin F. Butler, a criminal defense lawyer from Boston who had accrued a fortune by winning clients’ freedom on technicalities. Before the war, he had become known as something of a social activist for instituting a 10-hour workday—a reform at the time—in a mill he had purchased. Using his familiarity with legal loopholes, on May 24, 1861, Butler made what has come to be known legally as the “contraband” argument. Because the enemy considered slaves property, he reasoned, and because their labor was being used for the war effort, Butler concluded that runaway slaves were to be treated as any other illegal war goods would be—as contraband, subject to seizure by the Union, rendering them free.

Butler was “a lawyer first, and a general second,” says Michael Cobb, curator of the Hampton History Museum, adding, “He had the disposition to help people who were defenseless in many ways.” An agent for Charles King Mallory, the men’s owner, visited Fort Monroe to collect his “property,” and Butler explained that the law no longer applied in Virginia, which claimed to have seceded—but that he would return slaves to any owner who pledged loyalty to the Union.

“Butler’s fugitive slave law,” as it came to be known, drew thousands of slaves to Fort Monroe from as far away as North Carolina and Maryland, provided valuable Union labor, and represented a threat—real and existential—to local Confederate loyalists. Just months after Butler’s decision, on the order of Brigadier General John B. Magruder, the Confederate commander at Yorktown, the Confederates abandoned and burned Hampton. Their destruction of the city may have been intended as a provocation to the Union, but it had a different effect. It left a city’s worth of land and materials, albeit charred, for the newly freed people.

Two years before the Emancipation Proclamation, free African Americans built homes from the ruins. The example they set was emulated by other Union forts—more than 100 contraband camps would be set up before the end of the war. These safe havens took shape in federally held areas, such as Roanoke Island on the North Carolina coast; in Alexandria, Virginia; and in Washington, D.C.

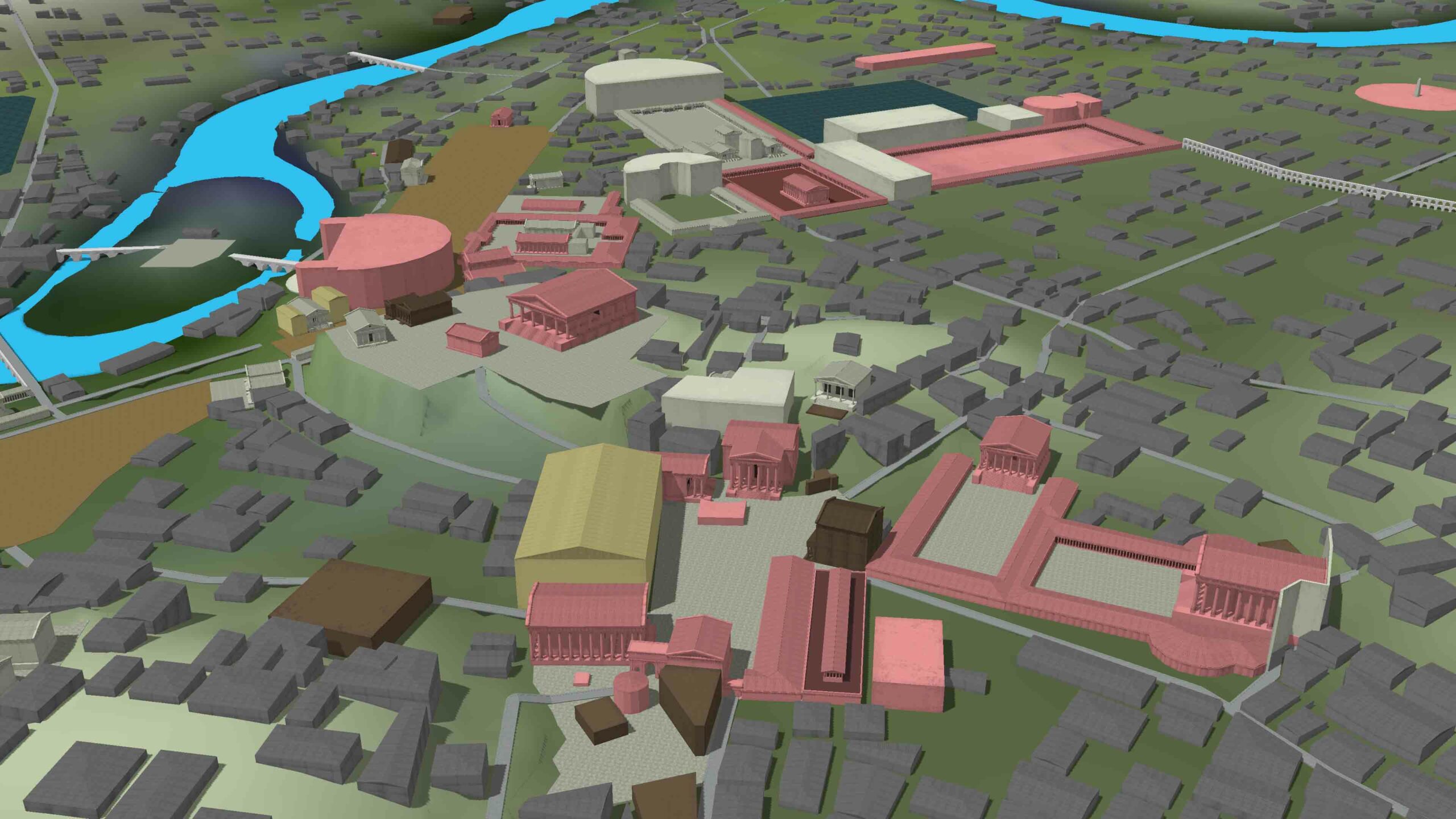

The Grand Contraband Camp in Hampton spread from Locust (now Eaton Street) to Big Bethel (now LaSalle Avenue), north to Mallory (now Pembroke Avenue) and south to Queen Street. During the Civil War, the camp began in a field about a quarter-mile from the city and adhered roughly to existing, if irregular, roads in the area. As it expanded, new street names appeared: Union, Grant, Lincoln—and Liberty, today’s Armistead Avenue, which led directly into the city. The camp then grew into parts of old Hampton, with some people building homes against still-standing chimneys.

By the end of the war in 1865, 9,000 people had cobbled together homes using doors, bricks, furniture, ceramic dishes, and cutlery left in the burned city. Unlike fugitive slaves, such as the maroons hidden deep within the Great Dismal Swamp nearby (“Letter from Virginia: American Refugees,” September/October 2011), the men of the Grand Contraband Camp worked for the Union, and federal troops may have helped with provisions. But in general, the contrabands were expected to be largely self-sufficient.

White residents returned at the war’s end, but the areas occupied by the contrabands remained primarily African-American neighborhoods. Over decades they evolved into a bustling district near the Hampton waterfront that today lies squarely within the city. And because the white owner of the field that first hosted the camp had gone bankrupt, the people who settled there were among the first African Americans in the nation able to purchase land and homes.

Over time, the area bordered by Armistead Avenue fell into blight, and was redeveloped with apartments in 1969. After years of deterioration, the Harbor Square apartments were purchased by the Hampton Redevelopment and Housing Authority and demolished in 2012, leaving the space open for excavation. Within a few feet of Armistead, separated from passing cars by only a sidewalk, a 40-by-16-foot trench revealed a neat layer of subsoil after archaeologists mechanically removed about 18 inches of heavily disturbed topsoil. “There is documentary evidence about the contrabands, since the army was here, and there were mission camps,” says Cobb, whose museum featured a contraband exhibit during the excavation. “There are records, reports, and descriptions of what the camp looked like and how people lived. The archaeology will fill in the places that aren’t in the documents. It will give us the first artifacts.” The artifacts and site are key to understanding the progression of a war that began as a conflict about states’ rights, and became a war of freedom, Cobb adds. “This precedent led to the Emancipation Proclamation. A major step was taken here.”

To ferret out an area undisturbed by the apartments or the lot division (from 1871), Matthew Laird, senior researcher and partner at James River Institute, examined 1870 census data, along with Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, which date to 1905 and were updated every 10 years. By overlaying Sanborn maps from different periods on an aerial photograph of the Harbor Square apartment complex, the team was able to identify promising targets for excavation. “It isn’t an accident that we were excavating in these spots,” says Laird. Over five weeks of the excavation in June 2014, archaeologists opened four trenches, exposing about 2,100 square feet in total. They found creamware, green wine-bottle glass, nails, and bones, as well as a U.S. Navy button dating to between 1812 and 1830 that could have belonged to a contraband service member. It is an interesting assemblage, but the true treasure of the site may lie in the soil itself.

Near the Armistead Avenue trench lies an assortment of shell and bone, probably food refuse, beside two dark circles in the soil, possibly postholes, at a right angle to the street. As with many excavations, particularly those that aren’t surpassingly rich in artifacts or building foundations, changes in soil color become critical clues for archaeologists. Because the contrabands built their homes without brick foundations and used a lot of organic materials, their lodgings and surrounding structures left distinctive marks in the subsoil. Changes in soil color can suggest the locations of root cellars, trash pits, wells, fences, and privies. Posts for a fence or structure, for example, decay into soil that is darker than what surrounds it, leaving distinctive circles. During the excavation, lines, lanes, and shapes in the subsoil were isolated and mapped. Half were then excavated. “So many features survive beneath the layers of modern fill, cutting into the subsoil,” says Nick Luccketti, principal archaeologist and partner in the James River Institute. “We believe we’ve found just the tip of the iceberg.”

Contraband-era features were distinguished from later ones by their relative orientation with respect to the street grid. Early features tend to be oriented along irregular thoroughfares. After the war, the streets became more regular, so later features were established in more geometric patterns, parallel to streets that still exist today. “Was the camp haphazard or was it regularly laid out?” says Laird. “We have noticed that some features appear not to be oriented to the street grid; they’re at weird angles. That’s a good indication that they predate it.”

So far, the archaeologists have identified more than 170 features, most, if not all, of which are associated with the Grand Contraband Camp. For example, they found a line near Armistead Avenue where the soil strata on one side had a yellow layer, and on the other side did not. Different fill types like this indicate a barrier between separate uses of land; in this case, the footprint of a board fence separating lots.

“That area has a lot of features crammed into a small area, and it gives you a sense that there was pretty dense occupation,” says Luccketti. “You sense there were a lot of people there.” The work ahead will include determining how the contraband camp was set up. Was it sprawling and without order, or did people have plots of their own? Did the residents plan its structure, or did the Union army give them a plan? Laird’s research reflects the land’s progression from field to contraband camp to neighborhood—a tidy transition with strong research and historical value.

The fields upon which the camp was established belonged at the time to Jefferson Bonapart Sinclair, who died in debt after the Civil War. The courts divided his land into long, narrow parcels, which created 93 urban lots, each 55 by 212 feet. Laird believes this division reflects the African-American settlement already in place.

“The lots were selling for $75,” he says. “They were affordable.” Selling the lots so soon after the war indicates a quick accommodation to the newly emancipated community. “You can see in the records, one after the other, African-American families were buying these lots,” Laird adds. For contrabands, the great risks they took for freedom may have paid off with a fast entry to landowning status and a better way of life—a seismic transition captured in the archaeology. “It’s interesting to look at these very early black landowners in Hampton, enslaved just five, six, seven years earlier,” Laird says. Indeed, the excavation offers a rare opportunity to see an early African-American neighborhood develop from a makeshift settlement to early homebuilding, with a new social structure, landownership, the establishment of churches and schools, a nascent economy, and some of the more personal benefits of a free life as well.

On a sunny June day, Joseph Dietmeier, senior field archaeologist with the James River Institute, is working on what appear to be animal bones—an articulated leg and hip, and a skull. A few days earlier, the archaeologists were examining an irregular clump of shells, bone, and refuse when they found an entire dog skeleton, along with a small buckle attached to a bit of leather. “It might suggest they had a pet,” Dietmeier says, a conclusion that fits other evidence. Another dog discovered at the site could date from the period, as Civil War soldiers reported stray cats and dogs roaming in Hampton. The contraband and later residents could have adopted these animals, Laird says. The simple act of owning a dog shows the cultural shift that took place in the late nineteenth century.

“People who are under immense stress and strain do not have the luxury of a pet,” says Laird, and the experience of the contrabands mirrors that of new immigrants to the country. “People arriving in this country for the first time are starting from scratch, from the ground up. They build a house, plant a garden, and now they are a family—and they get a dog. This is the first time they can make decisions for themselves to establish their own household. Having a dog factors in as evidence to underline that they could have a normal life.”

The legacy of the Grand Contraband Camp lives on, to some extent, in the modern population of Hampton. “People living here are related to the contrabands,” says Luci T. Cochran, executive director of the Hampton History Museum. “But a lot of them don’t know those stories. People are so moved by the contraband story, and they say, ‘I didn’t know this. It dramatically affected me.’ The contraband story really shaped our community.”

This unbroken line includes descendants of Merritt Thomas, a resident of the original Grand Contraband Camp, who purchased a lot in the sale of Sinclair’s property. “My mother grew up in a house that stood here,” says Runita W. White, one of Thomas’ descendants, who visited the site during the dig. White feels a deep bond with her ancestry, and appreciates the risks Thomas took to be free. “I’m proud that he was willing to take the chance,” White says. “The family stayed here and prospered.” The extended family celebrates its reunion at the nearby Bethel AME Church—founded by Thomas and others in 1864, not long after the camp was established. As the researchers complete their work, they believe they have evidence of features that will flesh out the contraband story. From their findings, the Sanborn maps, historical descriptions, and other records, they, along with the city of Hampton, which may continue to fund the project, will determine possible sites for future excavation.

“How often do you get something that’s a starting point?” asks David K. Hazzard of the James River Institute, a former state archaeologist for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources and one of the site’s researchers. “Slaves are in a free state, and the land stays in the African-American community. We’re beginning to connect the dots to create patterns of what people were doing in this space, from the earliest days to today.”