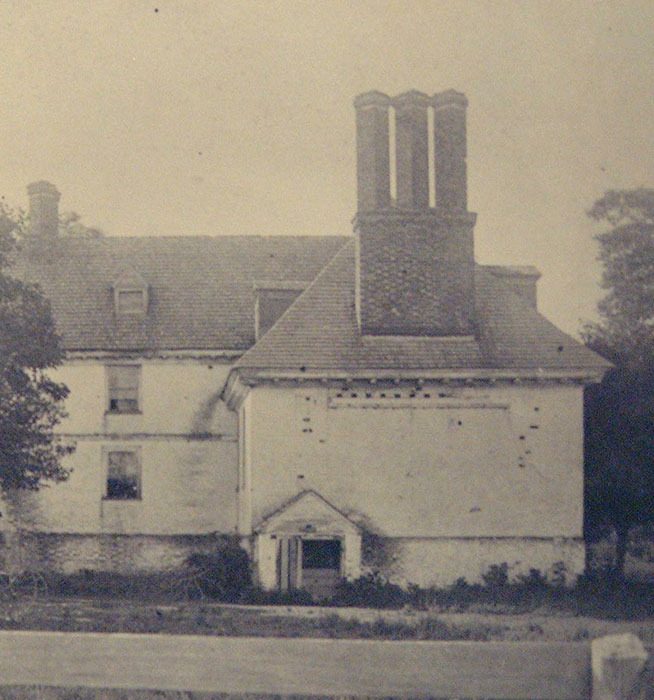

At the time it was completed in 1694, southeastern Virginia’s Fairfield Plantation was one of the largest and most architecturally innovative houses in the American colonies. Its distinctive features, including triple diamond-stack chimneys, hipped roof, and large, rectangular sash windows, made Fairfield “the most sophisticated classical house built in British North America to that date,” according to historian Cary Carson of the College of William and Mary. The 15,000-square-foot manor house would be home to generations of the Burwell family, one of eighteenth-century Virginia’s principal landowners. Two Burwells became members of the Governor’s Council, the upper house of the Colonial General Assembly, and one was an acting governor. Fairfield was also home to hundreds of enslaved people who planted and harvested the tobacco that supported the region’s economy. From 1787 to 1816, the property was owned by Col. Robert Thruston, a member of a prominent Virginia merchant-planter family, and thereafter it was occupied by several generations of African-American tenant farmers.

In 1897, a massive fire gutted the main house, which, at the time, belonged to an African- American woman whose name is unknown. After the fire, the house was torn down and the brick was sold or used to build nearby homes. Much of the cellar filled up with brick rubble and organic debris, sealing inside the burned wood and other artifacts that had fallen in at the time of the house’s destruction. A further century of neglect—interrupted only by an excavation in the 1960s—left what remained of Fairfield in ruins, with little hope for scholars to ever understand its story.

Now, thanks to an innovative 3-D printing project, archaeologists have the chance to learn more. The Fairfield Foundation was established in 2000 to support archaeological research at the plantation and in the surrounding region. Over the course of the last two decades, foundation archaeologists Dave Brown and Thane Harpole have excavated the manor house and unearthed artifacts including fragments of wine bottles and 30 seals that identify more than a century of Fairfield’s owners, as well as structural remains of at least 14 courses of its foundations and evidence of a cellar entrance that suggests the location of the original kitchen.

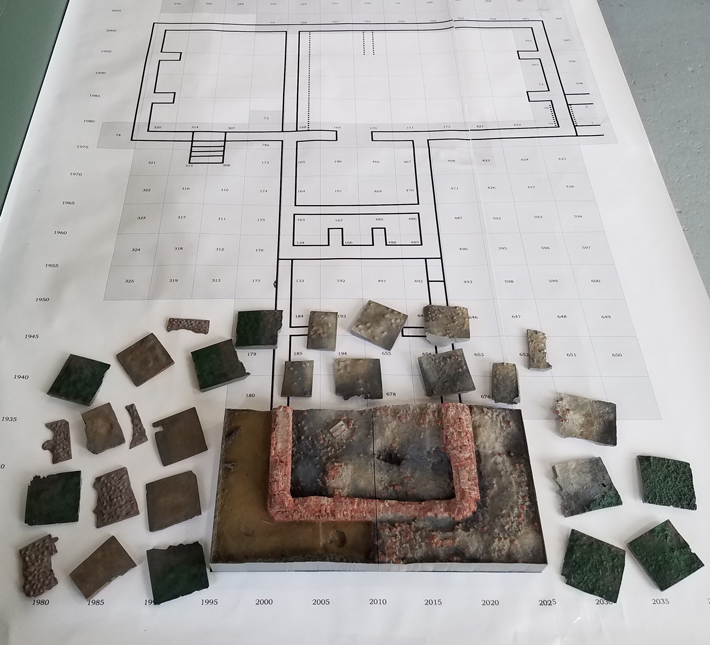

Building on these discoveries, foundation digital curator Ashley McCuistion is now leading a project to create a 3-D printed model that will accelerate the process of recording archaeological data and archive every surface of Fairfield, revealing details that have not been seen for centuries. To make the model, a camera mounted on a drone takes thousands of images of the excavation area. As each layer of soil is removed, the drone captures another set of images. These images are used to generate digital models of individual excavated layers, which are then printed in 3-D. The result is a plastic replica that easily fits atop a dining room table. “The part of the 3-D printing project that really captured my interest is that we’re doing it with a level of accuracy that no one has before. That’s something we’ve struggled with for a long time,” Harpole says. “Archaeology is destructive, so how do we get a perfect image of what we’ve dug?”

As the excavation proceeds, each new layer is incorporated as a removable piece of the model, which can then be built up and taken apart like Lego pieces. “The model has allowed us to represent the space in three dimensions and manipulate the layers in a hand-son way,” Brown says. This is crucial to learning how the house was built, how it was used, and how it changed over time. Brown explains that researchers can now also see how quickly the building is deteriorating. “We can now effectively identify changes such as cracks in the foundation, measure the rate of change, and focus our limited resources on selective stabilization where it matters most.”