CHINA

A rare high-ranking member of the famed Terracotta Army was unearthed in the mausoleum of China’s first emperor, Qin Shihuangdi (reigned 221–210 b.c.). Qin’s tomb is protected by thousands of life-size clay soldiers—his army for the afterlife. The recently uncovered figure depicts a top military officer, one of only 10 such figures identified among the 2,000 statues that have been excavated, and the first of such rank to be uncovered in 30 years. The officer’s elevated status is recognizable based on his posture, unique headdress, and colorful scale armor.

Related Content

ETHIOPIA

The 3.2-million-year-old australopithecine skeleton known as Lucy discovered more than 50 years ago is our most famous hominin relative. A new study has revealed that, while Lucy could walk on two feet, she couldn’t outrun an Olympic sprinter. Musculoskeletal modeling determined that Lucy’s top speed was about 11 miles per hour—modern elite runners have reached speeds of more than 23 miles per hour. This suggests that the ability to run ever faster may have been a significant factor in the evolution of modern humans.

Related Content

SYRIA

Focaccia has become a popular culinary staple, but people may have first enjoyed it 8,400 years ago in Mesopotamia. A study of enigmatic pottery sherds from Neolithic sites along the Syria-Turkey border indicates that they were part of large ceramic pans used to bake focaccia-like breads made from wheat or barley flour and seasoned with lard or oil. The pans were even nonstick—a series of impressions on the tray’s interior would have made it easier to remove baked bread.

Related Content

ISRAEL

People have taken shelter in the main chamber of Manot Cave for tens of thousands of years. Some even ventured into the darkest parts of the cavern for special gatherings. A stone carved in the shape of a tortoise was found in a niche of a hidden chamber located 8 stories below the cave’s entrance. Scholars believe the stone was likely an object of worship and that the chamber was used for ritual gatherings 35,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of such behavior in Asia.

Related Content

GREECE

During restoration of frescoes in the 15th-century Old Monastery of Taxiarches in Aigialeia, workers uncovered the only known portrait of the final Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. The emperor wears a purple robe embellished with a double-headed eagle, the insignia of the imperial family. Scholars believe that Constantine personally sat for the artist shortly before he died in the 1453 battle in which Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, ending the Byzantine Empire.

Related Content

GERMANY

Archaeologists excavating a mid-third-century a.d. Roman necropolis in the town of Nida unearthed the grave of a man buried with a 1.4-inch-long silver amulet. Further inspection revealed that the object contained a tiny rolled-up piece of silver foil that was too brittle to unfurl. Researchers used CT scanning to digitally unroll the scroll, revealing, to their surprise, a Christian text. Christianity was very rare at this time, and the minuscule inscription is the earliest evidence of its spread north of the Alps.

Related Content

THE NETHERLANDS

While investigating a 400-year-old building in Alkmaar, archaeologists uncovered an earlier tile floor, which in and of itself isn’t unusual. A number of floor tiles were missing—also not unusual. What was out of the ordinary, however, was that a portion of the surface had been patched with cattle bones, each one meticulously cut and carefully placed. Experts are unsure why residents took such an unusual step: Was it indicative of activities that occurred in the building or simply an inexpensive DIY fix?

Related Content

BOLIVIA

It had long been thought that, in the precolonial era, the Amazon Basin’s environment was unfavorable for both food production and large-scale human settlement. However, archaeologists now know that the Indigenous Casarabe peoples thrived in the Llanos de Mojos region between a.d. 500 and 1400 by relying on maize cultivation. New isotope analysis of animal bones also indicates that the Casarabe domesticated local Muscovy ducks as early as a.d. 800 by feeding them maize.

Related Content

FLORIDA

Burrfishes are rarely eaten because they can be lethal to humans. Curiously, massive amounts of burrfish remains were found at Mound Key, capital of the Indigenous Calusa people prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. The Calusa were masters at manipulating their marine environment, but archaeologists don’t know why they harvested this deadly species. They speculate that the Calusa may have used burrfish toxins for medicinal or religious purposes or employed the spines as tattooing needles or spear tips.

Related Content

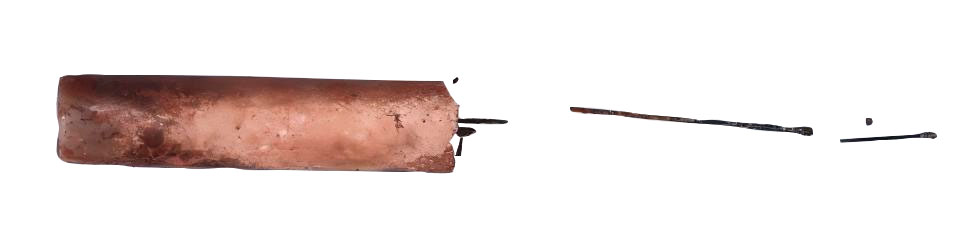

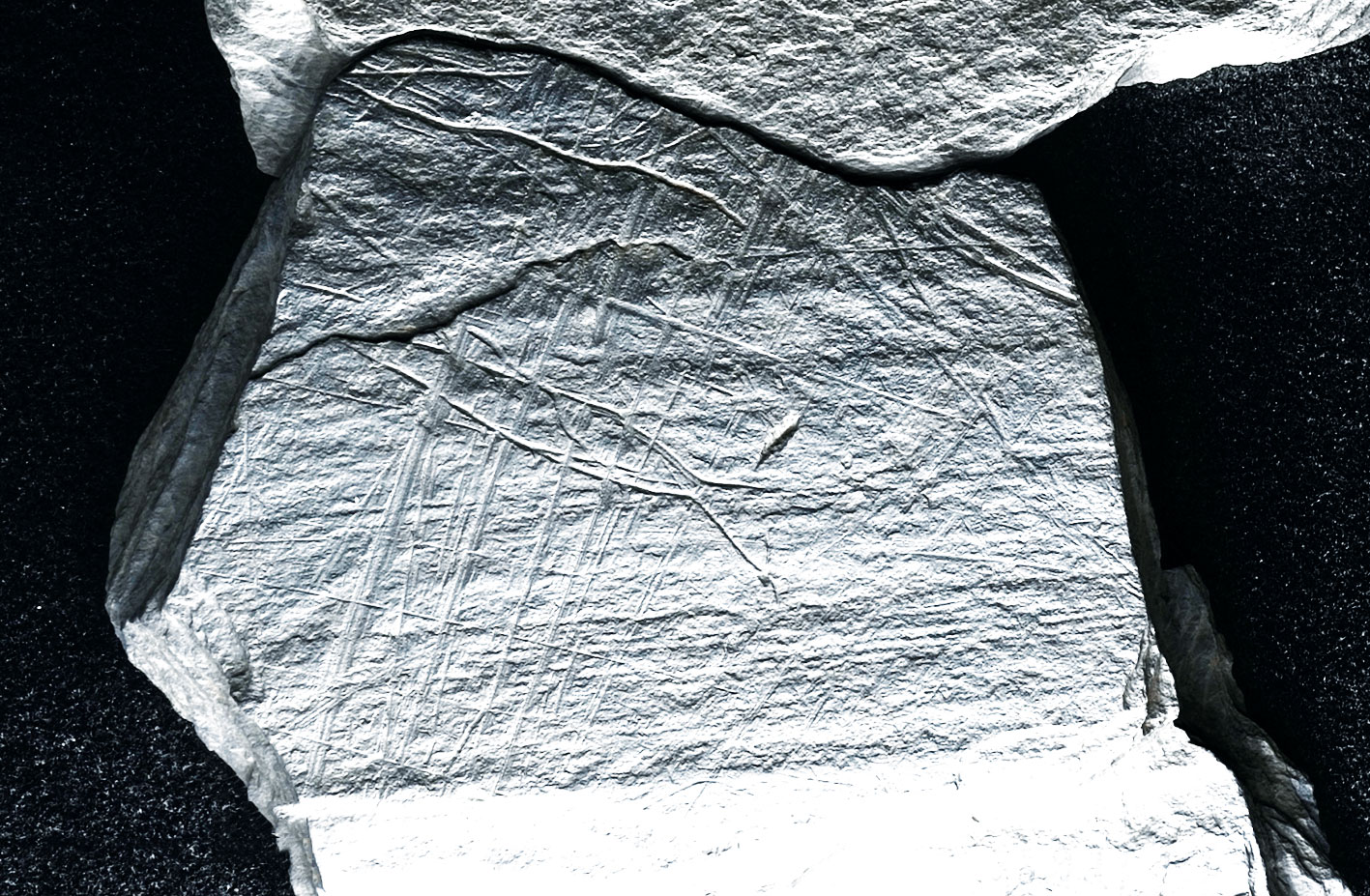

ARIZONA

A small cannon likely associated with Spanish conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s 1540–1542 expedition through the American Southwest may be the oldest firearm ever found in the continental United States. The weapon, which is 42 inches long and weighs 40 pounds, was discovered at the site of San Geronimo III, where Coronado’s men established a settlement along the Santa Cruz River. The outpost was attacked by the Indigenous Sobaipuri O‘odham in 1541. The Spaniards fled, leaving the gun behind.