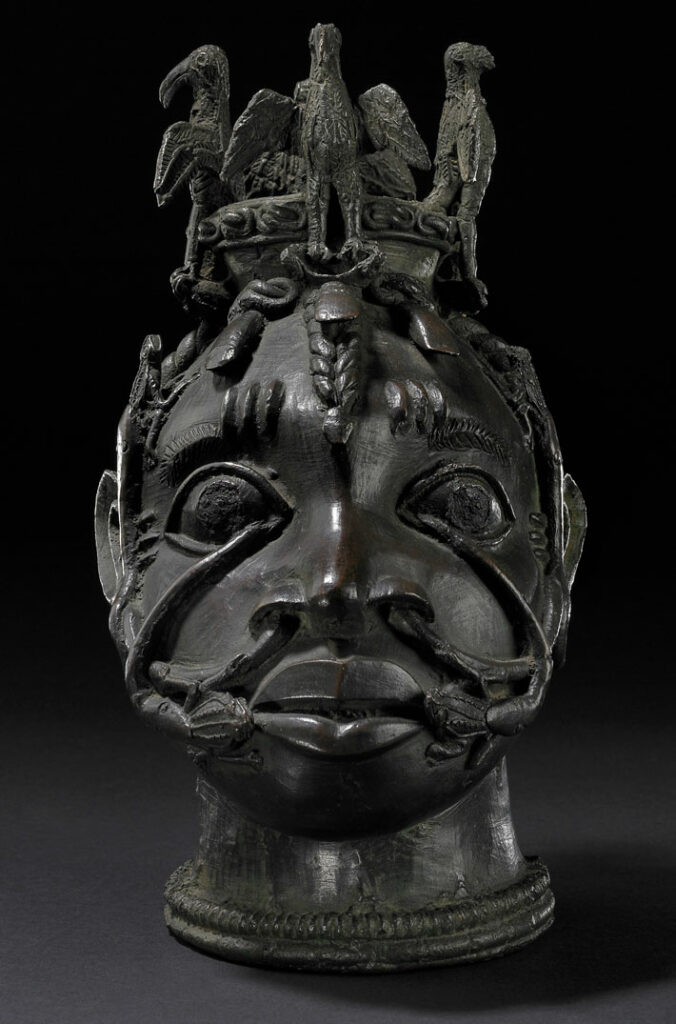

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Edo people of the Kingdom of Benin, which controlled territory on the west coast of Africa that is now part of Nigeria, produced thousands of artworks that have come to be known as the Benin Bronzes. The works, which once decorated the kingdom’s royal palace, include personal ornaments, animal and human figurines, plaques that illustrate the kingdom’s history, and sculpted heads of its obas, or kings. A large quantity of the objects were looted during an 1897 British military expedition. Many of these are held in museums and private collections around the world and are the subject of ongoing repatriation efforts.

Despite their name, the majority of the Benin Bronzes were actually made of brass, while others were crafted from materials such as ivory, coral, leather, and wood. The precise origin of the brass used to make the metal objects has long been a mystery. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. It often includes other elements as well, in particular lead, which is typically present in zinc ore. The ratio of different forms, or isotopes, of lead in a given sample of brass acts as a metallic fingerprint that can help identify its source. Research on the bronzes’ lead isotope ratios has produced tantalizing hints that the brass used to make them came from one specific area. For example, a study of 212 bronzes found that the lead isotope ratios of 113 of them were so similar that the zinc used to produce their brass had likely been sourced from a single mining deposit. The others differed only slightly and appeared to contain zinc sourced from nearby.

It has long been suspected that the raw metal used to craft the Benin Bronzes came from manillas, horseshoe-shaped brass rings that were used as currency by Europeans to trade with West Africans, primarily for slaves, but also for goods such as ivory and spices. However, until recently, efforts to establish a scientific link between manillas and the artworks had come up short. “Metallurgists who analyzed manillas said they couldn’t be the source because the materials were too impure,” says Tobias Skowronek, a geochemist at the Technical University of Georg Agricola. He notes that the manillas in question were essentially alloys of copper and lead that included high levels of antimony and arsenic, elements that degrade the quality of the metal and result in cracking. The problem with these earlier studies, according to Skowronek, is that researchers were looking at the wrong types of manillas. “Their analysis focused only on materials from museums,” he says. “Most manillas in museums date to the twentieth or sometimes the nineteenth century, and don’t have anything to do with the material that was shipped during the period of the transatlantic slave trade.”

Now, a team led by Skowronek has analyzed a much broader range of manillas dating from the fifteenth to nineteenth centuries recovered from five shipwrecks and three land sites in West Africa, Western Europe, and off the East Coast of the United States. At least some of the ships from which the manillas were retrieved are believed to have plied the Triangle Trade. This involved trading manillas for West African slaves, who were brought to the Americas and sold. The ships would then return to Europe with goods such as sugar, cotton, and tobacco. Following a classification system developed by team member Rolf Denk of Eucoprimo, an E.U. organization that studies unusual forms of money, the researchers divided the manillas into three different types: early examples known as tacoais, which were traded by the Portuguese; a later style called Birmingham manillas, which appeared beginning in the eighteenth century; and a transitional type known as popo manillas.

By studying the lead isotope ratios of each of these types of manilla, Skowronek’s team determined that the brass in the tacoais type was used to make the Benin Bronzes. They also found that the lead isotope ratios of the tacoais manillas were strikingly similar to those of lead-zinc ores mined in Germany’s Rhineland. Given that the process of smelting brass uses up a great deal of zinc, it generally took place near the zinc source. Thus, the researchers concluded, the tacoais manillas must have been produced in the Rhineland.

Skowronek believes the Edo metalsmiths who crafted the Benin Bronzes were undoubtedly aware of the superior qualities of the tacoais manillas and likely demanded them in trade. “These early Portuguese manillas are brass with a high lead content, an alloy that is easy to smelt,” he says. “If you want to make an art object like the Benin Bronzes, you need to have a metal that flows easily when melted, and the high lead content of these early manillas is responsible for that.”