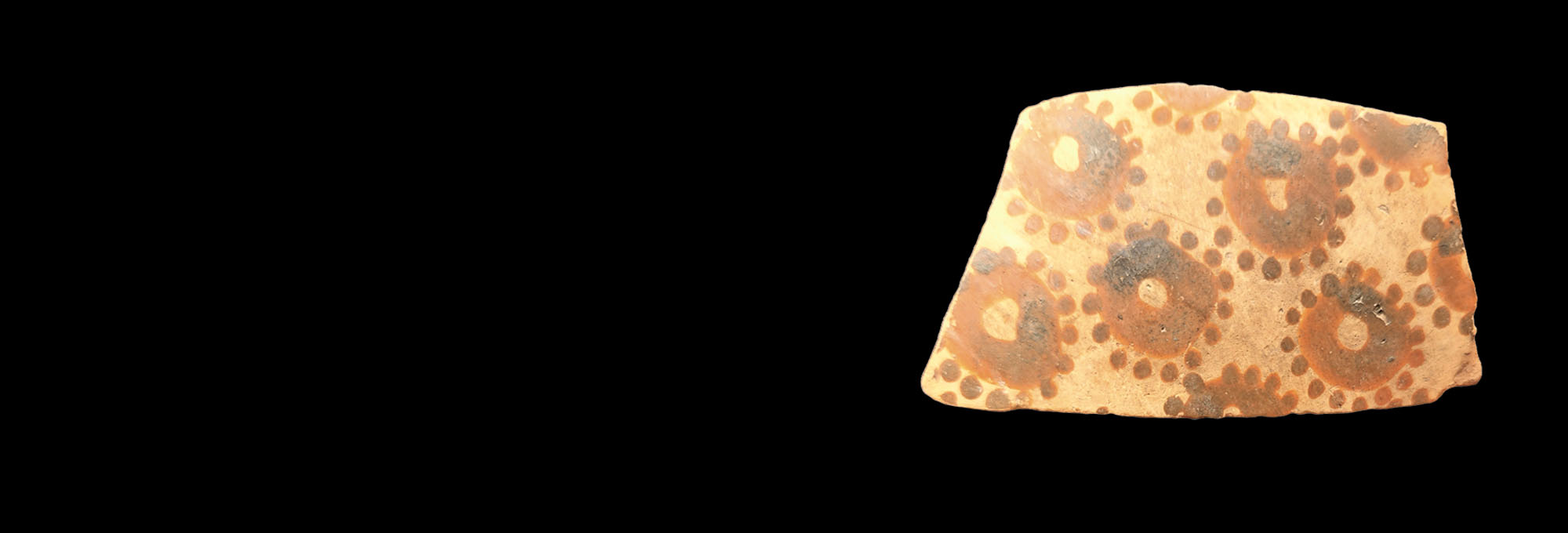

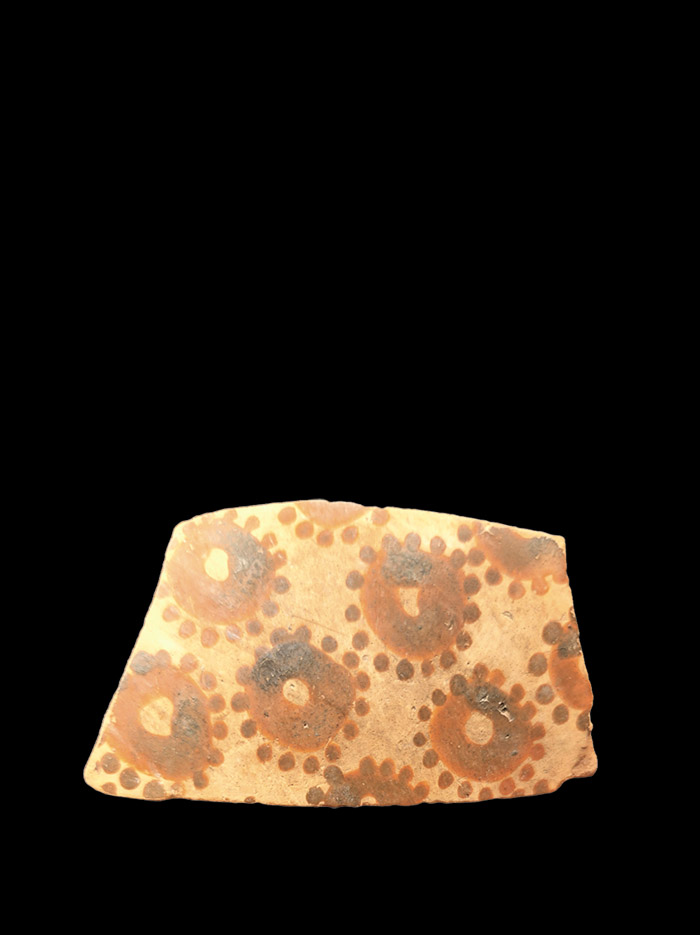

Beginning at least 51,000 years ago with an image of a pig in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, people have made illustrations of animals. Yet they don’t seem to have drawn plants until many millennia later. In fact, says archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the earliest depictions of floral motifs don’t appear until about 6200 b.c. on pottery vessels made by members of northern Mesopotamia’s Halafian culture. Archaeologists have found hundreds of images on potsherds showing shrubs, trees, and, most prolifically, flowers in at least 30 Halafian sites. “They’re the first examples of botanical representations in human art,” says Garfinkel. “It’s really surprising because they aren’t images of fruit or wheat or other things people are eating, so it’s not connected to fertility rituals or anything like that.”

According to Garfinkel, these images appear to provide evidence of a mathematical system members of the Halafian culture used to divide their land and harvests. “If you have a village, and people are working in the fields, they need to share crops among families,” he says. “To share equally starts with dividing things in two, then four, then eight, and so on.” Garfinkel noticed that flower petals on many pots appear in sets of those numbers. “This reflects a cognitive shift tied to village life and a growing awareness of symmetry and aesthetics,” he says. “I think that there was this mathematical knowledge in the village and that potters painted with this in mind. It’s an echo of that knowledge thousands of years before writing.”