Editor Discusses World War II Archaeology on NPR's Here & Now

Cracking the Code

Gearing Up at the Desert Training Center

YP-389 and the Battle of the AtlanticSlideshow: The Story of YP-389

London's Air-Raid Shelters and Lost Homes

World War II Aircraft Crash Sites

Unexploded War Relics

The Early Days of Nuclear Warfare

The Sinking of the HMAS Sydney

The POW Camp Made Famous by The Great Escape

Between 1939 and 1945, the world was engulfed in a conflict fought on almost every continent and ocean, involving every world power, and ultimately costing more than 50 million people, both soldiers and civilians, their lives. More than a dozen nations, among them the United States, Great Britain, and the U.S.S.R, fought on the side of the Allies, joining forces against the Axis powers—primarily Germany, Italy, and Japan—who, at the apex of their power, controlled or were poised to control large swaths of Europe, Africa, the Pacific Ocean, and East and Southeast Asia. Perhaps the greatest difference between World War II and the wars and conflicts that preceded it was its ubiquity.

For the first time, there were no clearly defined front lines where battles began and ended, were won and lost. Instead, according to University College London archaeologist Gabriel Moshenska, who studies the archaeology of modern conflict, "Everyone was on the front line and that transformed the world. World War II made the modern world what it is more than any single event in history," he says. "It changed the technology we use, it changed art and literature and the world's legal, international, and political structures—everything from nations to families."

This new kind of warfare, for archaeologists, requires a different approach to studying military action. The traditional methodology of battlefield archaeology—identifying a battle's location, unearthing weapons and defensive structures, and evaluating historical and literary texts—is not sufficient to understand World War II's geographic reach and social impact. What is needed, according to Tony Pollard, Director of the Center for Battlefield Archaeology at University of Glasgow, is a new kind of archaeology, one that he has dubbed "conflict archaeology." "Conflict archaeology is valuable because it places the violent events of warfare within their wider social context," he says, allowing for a broader understanding of twentieth- and twenty-first-century war.

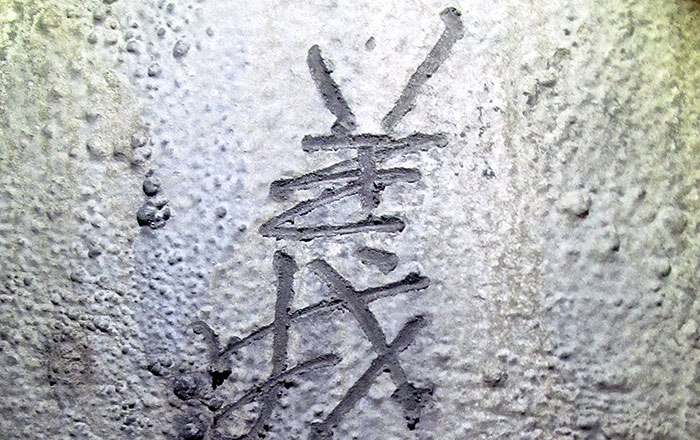

The excavations and finds covered here do examine how familiar facets of war—tactics, weapons, technology, and intelligence—can be seen in the archaeological record. There are submerged tanks, downed airplanes, a cryptological machine, and a forgotten remnant of the nuclear weapons the United States used on Japan, which both helped end the war and changed the world forever. But the story of World War II is not only about the last century's military technology. It is also about the particular ways global conflict affected civilians.

The study of World War II is at a critical juncture. We are now at a time when both veterans and civilians who participated in and lived through the war—on the battlefield and on the home front—are passing away in greater numbers. With their deaths, the chance to hear their stories and learn from their experiences disappears as well. "Their testimony is a living bridge between the present and the past that will soon be nonexistent," says Pollard. But archaeology also has stories to tell. According to Moshenska, the degree to which archaeology can illuminate things that are not revealed elsewhere is only now being recognized. "These are not part of the official histories, and although they are sometimes part of people's memories, those memories become more unreliable as more time passes." The archaeology of this world-changing time supplements these memories, and in some cases tells us stories we would never know otherwise.