Pork accounts for more than a third of the world’s meat, making pigs among the planet’s most widely consumed animals. They are also widely reviled: For about two billion people, eating pork is explicitly prohibited. The Hebrew Bible and the Islamic Koran both forbid adherents from eating pig flesh, and this ban is one of humanity’s most deeply entrenched dietary restrictions. For centuries, scholars have struggled to find a satisfying explanation for this widespread taboo. “There are an amazing number of misconceptions people continue to have about pigs,” says archaeologist Max Price of Durham University, who is among a small group of scholars scouring both modern excavation reports and ancient tablets for clues about the rise and fall of pork consumption in the ancient Near East. “That makes this research both frustrating and fascinating.”

Among the most surprising finds is that the inhabitants of the earliest cities of the Bronze Age (3500–1200 b.c.) were enthusiastic pig eaters, and that even later Iron Age (1200–586 b.c.) residents of Jerusalem enjoyed the occasional pork feast. Yet despite a wealth of data and new techniques including ancient DNA analysis, archaeologists still wrestle with many porcine mysteries, including why the once plentiful animal gradually became scarce long before religious taboos were enacted. Ultimately, the tale of the pig in the ancient Near East reveals how humans thrived in the first cities, the ways in which economic inequality shaped early urban societies, and the important role that diet played in defining ethnic groups and distinguishing friend from foe.

Pigs are prolific. A single sow can mother up to 100 piglets, far more than sheep, goats, or cows, and their offspring can reach maturity in about six months. They require less than half the amount of water needed by a cow or a horse, making them more drought tolerant. In many parts of the globe, past and present, pigs root through trash, converting noxious garbage into nutritious food. Today, one billion pigs are slaughtered annually to produce a wide array of food products, including pork chops, ham hocks, bacon, and lard.

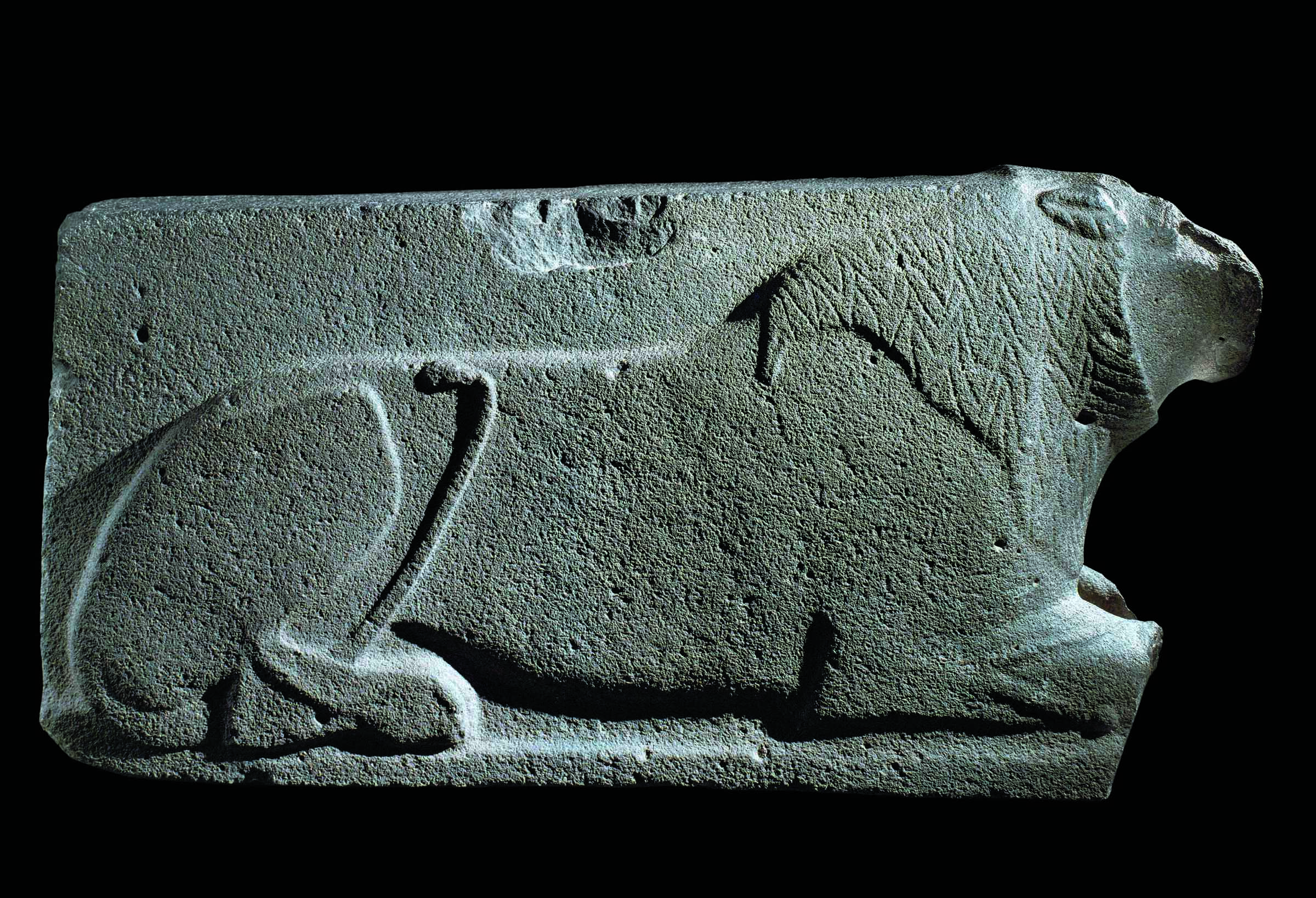

The domestic pig’s story begins with the wild boar, Sus scrofa, which roamed Southeast Asia more than five million years ago and slowly spread across Asia into Europe. Early humans hunted this intelligent, fierce animal across both continents. Some 10,000 years ago in the Near East, and a few millennia later in China, S. scrofa began to transform into S. scrofa domesticus. Precisely how this took place is only now coming into focus.

In the 1990s, at the site of Hallan Çemi in southeastern Anatolia, archaeologists unearthed 51,000 animal bones dating to about 10,000 b.c. Of these, boar bones made up nearly one in five of the recovered remains, suggesting that the animal was an important source of meat. Researchers also found that nearly half the boars were less than a year old when killed, and that most of the rest were under three.

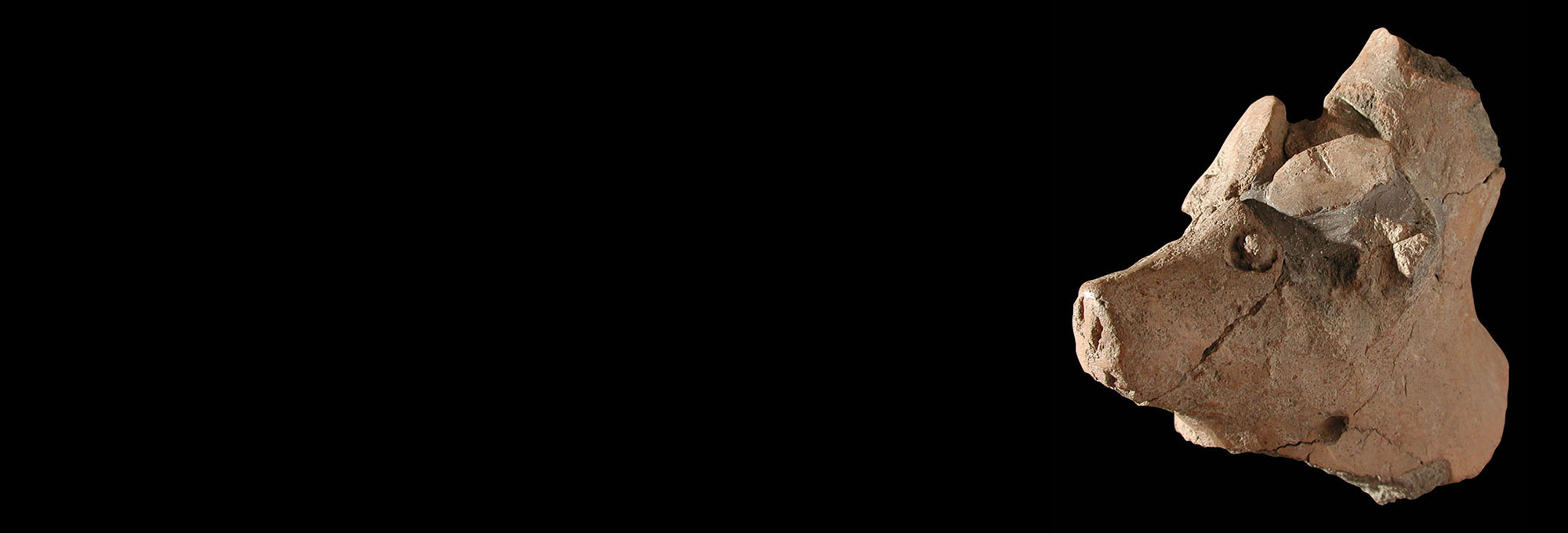

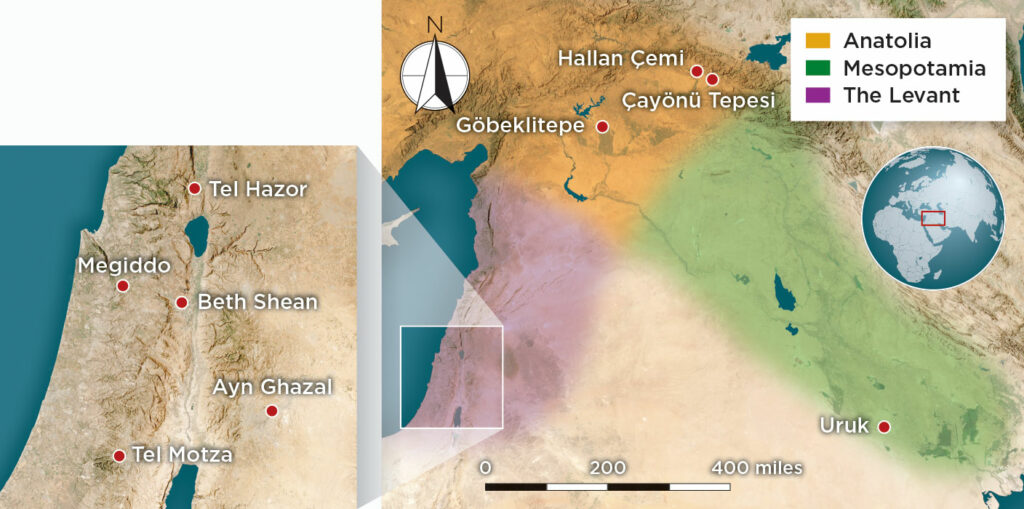

Archaeologist Melinda Zeder of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History argues that settlements such as Hallan Çemi mark the start of the long process of pig domestication, which began around the same time humans started to live in permanent settlements and to transform wild grasses into cultivated grain. “Boars were drawn to places humans inhabited, with their accumulation of trash, as well as to their fields,” Zeder says. The animals’ proximity allowed hunters to pick and choose their prey. “People had a culling strategy that encouraged the growth of herds,” she adds, noting that hunters targeted young male boars and allowed sows to live in order to breed. Pigs’ significance to the people of these early settlements is reflected in the numerous representations of wild boars that have been discovered at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (ca. 10,000–8200 b.c.) site of Göbeklitepe, also in southeastern Anatolia.

At another site in the region, called Çayönü Tepesi, which began to be settled around 8600 b.c., archaeologists excavating from the 1960s to the 1990s unearthed a number of boar molars and skulls that came from younger animals and were smaller than those dating to the beginning of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. Zeder believes that these morphological changes show that the people living at Çayönü Tepesi—and, almost certainly, at other settlements in the area—were beginning to put the wild animal on the path to domestication.

The first site in the Near East where archaeologists have found unmistakable evidence of pig domestication is Tel Motza, a large Neolithic settlement established around 8600 b.c. in what is now Jerusalem. In 2012, archaeologists uncovered large numbers of bones there dating to just after 7000 b.c. that show clear signs of traits associated with the fully domesticated pig, which is smaller, shorter-faced, and more docile than its wild cousin. Further excavations across the region have shown that S. scrofa domesticus appeared not long after at other Neolithic sites.

The spread of domesticated pigs was slower and more uneven than it was for sheep and goats, which were domesticated at roughly the same time. Pigs appear to have thrived in areas with access to water and forests where they could forage for nuts. These omnivorous animals not only provided copious meat, but also cleaned up food scraps and human waste that might attract pests or spread disease. Caches of deliberately buried bones at Neolithic sites provide evidence that people slaughtered pigs for barbecues that may have encouraged social cohesion as well as serving as a nutritious meal. At the site of Ayn Ghazal in Amman, Jordan, a Neolithic settlement inhabited by some 3,000 people that flourished from around 7200 to 5000 b.c., archaeologists in the 1980s found pig skulls buried with those belonging to humans, indicating that people perceived the animal as important in ways beyond its utility as a food source.

With the growth of the world’s first urban areas, starting in southern Mesopotamia around 3500 b.c., pigs found their niche. Yet their central role in the development of the earliest cities in what is now southern Iraq has been overlooked and underestimated. “We often imagine Mesopotamian foodways in the Bronze Age as having no pigs, but most meat eaten in the largest cities was pork,” Price says. “Big cities are fantastic places to raise pigs. They have shade, stagnant water, and are protected from predators.” And they have lots of trash.

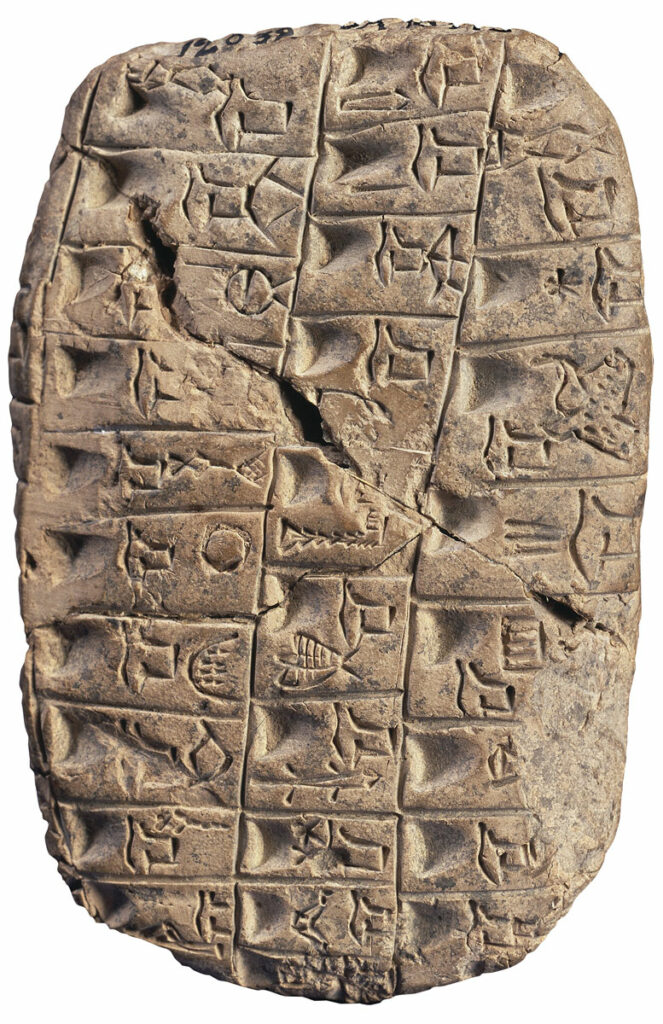

Although archaeologists have found large numbers of pig bones at early cities such as Uruk, ruminants—animals including cows with four-chambered stomachs that can digest grass—dominate the written record that evolved in tandem with urban life. Herds of sheep, goats, and cattle were relatively easy for government officials to oversee, says Price. Not so pigs, which can live, breed, and be slaughtered quickly in a backyard lot. The swine didn’t need grazing land, just the day’s leftovers. “Large-scale management of pigs really wasn’t possible,” says Zeder. “The small-scale nature of pig raising became a beacon for the urban poor. It existed as a sub-rosa element of the economy.”

Thousands of clay tablets uncovered across Mesopotamia show that scribes gave short shrift to an animal that was difficult to tax. And excavations reveal that those living in wealthy households, palaces, and temples came to prefer mutton and beef, likely reflecting pork’s lowly reputation. Ruminants also provided lucrative secondary products including milk and wool, which became economic mainstays for better-off residents of these first cities.

The Hittites, who ruled over Anatolia from around 1600 to 1200 b.c., are known to have commonly sacrificed pigs in ritual acts. As the Bronze Age progressed, however, swine were gradually excluded from rituals across the region, and pork consumption dropped. By 1600 b.c., less than one in 20 bones found at sites in the Levant typically come from pigs, and most of those appear to be wild boars that were hunted. At the dawn of the Iron Age, some 500 years later, pig-rearing had virtually ceased. “There’s no sign of a sudden taboo, disease, or environmental change,” says Price. “What is clear is that sheep, goats, and cattle took over.” Price suspects that a host of factors contributed to this gradual decline, including more frequent droughts, loss of nut-bearing forests, and the rise of the wool and milk-product trade. “Pigs lost their status,” Price says, as they were increasingly seen as scavengers with an insatiable appetite for food and sex. The stage was set for a more widespread and all-encompassing taboo.

Most scholars believe that the Hebrew Bible was written down in Jerusalem between around 600 and 300 b.c. The Book of Leviticus contains a warning that the pig “is impure to you; from their flesh, you shall not eat, and their carcasses you shall not touch.” Many historians assume that this prohibition reflects an ancient tradition that stretched back to the Israelites, who, by 1200 b.c., lived in the highlands of the southern Levant with flocks of sheep and goats and herds of cattle. The absence of swine in the archaeological record of such settlements in this rugged region is no surprise. “In the majority of cases,” Price says, “a mobile, pastoral way of life, especially in the Near East, generally does not include raising pigs.”

Yet to the west, along the Mediterranean coast, archaeologists have found abundant evidence of pork consumption in contemporaneous cities associated with the Philistines, who are thought to have arrived with the Sea Peoples from the Aegean around 1200 b.c. The Philistines built cities in what are now Israel and Gaza, creating a loose confederacy. (See “The Philistine Age.”) They also brought their own pigs. Tel Aviv University archaeologist Meirav Meiri has extracted DNA from ancient pig remains in Greece and Israel and found that varieties of European pigs had swamped the local gene pool by around 900 b.c. and became dominant.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Philistines are the Israelites’ chief nemesis. For archaeologists who consider the contrast in pig consumption between the two groups to be a reliable marker of ethnic identity, the story went that if you dug a site in the region without pig bones, you had found an Israelite settlement. “Or so it was thought,” says archaeologist Lidar Sapir-Hen of Tel Aviv University. Additional finds, along with more accurate dating techniques, now show that the Philistines weren’t voracious pork eaters after all. Pig bones in large Philistine cities rarely account for more than a fifth of the meat that people consumed. In nearby smaller towns and villages, that figure drops to just 1 percent. “After the tenth century b.c.,” Price says, “the Philistines have largely given up pork in urban as well as rural areas.” These settlers came to imitate their neighbors, including the Israelites, and sheep, goats, and cattle became the favored meats on the menu.

At the start of the Iron Age, the story of the pig in the Near East takes a surprising turn. Archaeologists have detected an uptick in pork consumption in the region around 1000 b.c. This was about the time that the Israelites conquered Jerusalem by defeating a local Canaanite tribe and made it the capital of what became known as Judea. “There’s a creeping increase in pigs at this time, primarily in the northern kingdom of Israel,” says Price. At the urban sites of Megiddo and Tel Hazor, for example, excavators have unearthed butchered pig bones dating to the period between 1000 and 586 b.c., while at the site of Beth Shean, they have discovered that one in 12 bones belonged to swine.

Even Judeans, who scholars had assumed avoided pork, weren’t, it seems, immune to the lure of a pig roast. Sapir-Hen was part of an Israel Antiquities Authority team in 2021 that examined a complete pig skeleton dating to about 700 b.c. that had been unearthed in the heart of Jerusalem. The seven-month-old animal died when a building associated with a wealthy family collapsed. Had the young animal survived, it likely would have ended its days at the slaughterhouse—other pig bones that were found nearby have butchery marks. Whether this pig was destined for the plates of lowly servants or those of the well-to-do family isn’t clear. Although only about one in 50 animal bones found from this era in Jerusalem are from pigs, these discoveries show that eating pork wasn’t unheard of among some city dwellers, even those living in prosperous homes in the middle of town. “Every excavation in Jerusalem and Judah from the same period has found some pig bones,” says Sapir-Hen.

Why the prohibition on pork was codified in the Hebrew Bible has long been disputed. Some scholars argue that the taboo was a way to discourage rearing an animal unfit for the harsh terrain and dry climate of the Levantine highlands. Others insist the taboo was a health measure intended to prevent the spread of trichinosis, a parasite that can lurk in undercooked meat and inflicts sufferers with diarrhea, vomiting, and fever. One scholar posits that the domesticated chicken’s arrival from Iran provided an alternative to raising pigs.

Price points out, however, that none of these theories fully accounts for the taboo. Pig-rearing, after all, had existed for thousands of years in the region, even in times of drought, and many types of meat can harbor the larvae that cause trichinosis. Moreover, chickens didn’t become common in Near Eastern farmyards until centuries after the Hebrew Bible was written. For Price, the key piece of evidence is the sole reason given for the taboo in the biblical text—the fact that the pig “has hooves and does not chew its cud.” In other words, it’s unlike ruminants. He argues that this harks back to an era when the Israelites were simple pastoralists. As their descendants settled down in towns and cities, raising pigs became a more viable option. “This detracted from the fantasy of living like their ancestors,” says Price, prompting Judean priests to ban eating pork.

At the time, according to Jordan Rosenblum, a scholar of classical Judaism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, pigs were just one of many prohibited foods. “The Hebrew Bible equally bans eating the pig, the camel, the hare, and other animals,” he says. Fish without scales, rock badgers, and certain birds were also off-limits.

Rosenblum argues that the pig taboo only gained special status with the invasion of the Levant by the forces of the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great in 332 b.c. These European conquerors enjoyed their pork, and pig consumption in the Levant soared. So did tensions between Judeans and their Hellenistic rulers, including the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt and the leaders of the Seleucid Empire based in today’s Iraq.

Archaeologist Yonatan Adler of Ariel University argues that Judaism didn’t emerge as a fully codified religion until at least the second century b.c., partly in reaction to Hellenistic domination. Rosenblum cites a story from the Second Book of Maccabees, which dates to the second century b.c. in which a group of Judeans forced by Hellenistic officials to eat pork chose martyrdom instead. He says that such tales underscore how the prohibition against eating pork emerged as a symbol of political and religious identity.

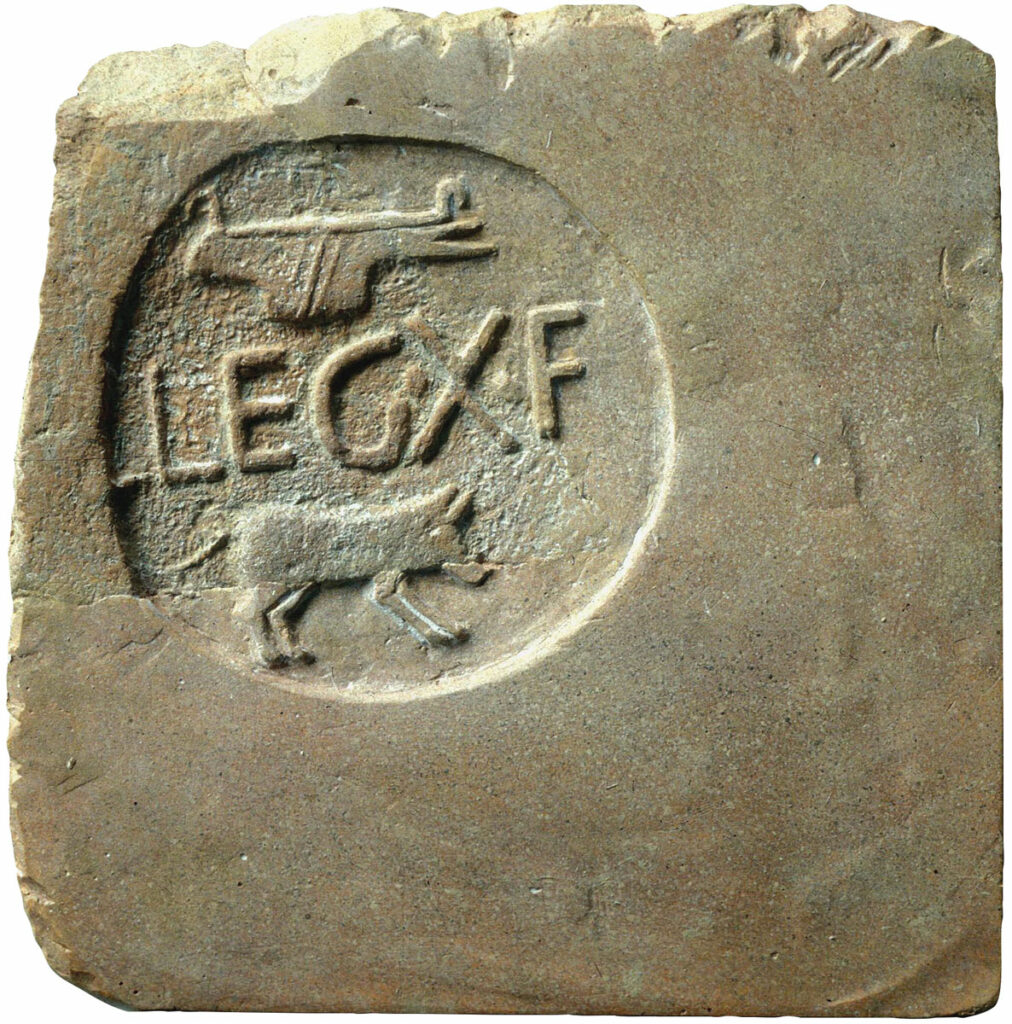

The Hellenistic kingdoms collapsed in the first century b.c., only to be replaced by the Romans, whose enjoyment of pork repasts was even greater than the Greeks’. Rome’s legendary founders, Romulus and Remus, were sometimes depicted as suckling on a wild sow. Pigs were often ritually sacrificed, and two Roman legions chose a boar as their emblem. When Rome annexed Judea in 63 b.c., soldiers brought herds of large, fast-growing pig varieties, and the animal once again became a common fixture of the Near Eastern diet—except among Judeans.

First-century a.d. Roman writers including Apion and Seneca puzzled over the Jewish prohibition on eating pigs, along with the practice of circumcision and observance of the Sabbath. Their confusion could shade into mockery. “One of the most significant developments in the classical period was the weaponization of pork against the Jews,” says Price. Rosenblum adds that among the emerging class of Jewish teachers known as rabbis, pigs became a symbol of corruption, greed, oppression, and violence, all of which they associated with Rome. Stories about Jews killed by Romans when they refused to eat pork proliferated. “Rome becomes the pig,” says Price.

Nevertheless, archaeological evidence shows that people continued to eat more and more swine in the southern Levant in the first few centuries a.d., returning to levels not seen since the early Bronze Age. By this time, followers of the nascent Christian religion had rejected Jewish dietary restrictions, in part to attract non-Jewish followers. Pigs remained a staple in the Levant through the first centuries of the Byzantine period. That began to change with the arrival of Islam in the region in the a.d. 630s. Muslims took a middle ground, rejecting most Jewish dietary restrictions but accepting the prohibition on pork. The Koran says the pig is unclean and therefore forbidden, along with blood, dead animals, and animals not dedicated to Allah. This taboo likely did not force a significant change on the faith’s followers: Pre-Islamic sites excavated on the Arabian Peninsula contain few pig bones. This is unsurprising, given the hot and very dry climate and the primarily pastoralist lifestyle on the peninsula.

Although pork consumption declined with the rise of Islam, it never stopped completely. Despite climate change, shifting food fashions, and outright religious bans, people in the Middle East have been raising pigs for at least 10,000 years. In today’s Israel, Palestinian Christians continue to enjoy pork barbecues. There is even a Jewish kibbutz where pigs are raised for medical research, and the surplus meat is sold. The animal that Price calls “intelligent, curious, and social” seems destined to remain an inextricable part of the region’s foodways.