JAPAN

JAPAN: At the Kami-Goten site in Shiga Prefecture, archaeologists have uncovered two siltstone molds for casting bronze daggers, dating to between 350 B.C. and A.D. 300. The design of the daggers—cast as a single piece with a long, straight blade and two rings on the pommel—presents a bit of mystery. It resembles dagger designs used by equestrian nomads in northern China and Mongolia, but contact between the regions would have been very unusual at the time. Perhaps the rulers of the area had established a trade route that brought such influences to them. —Samir S. Patel

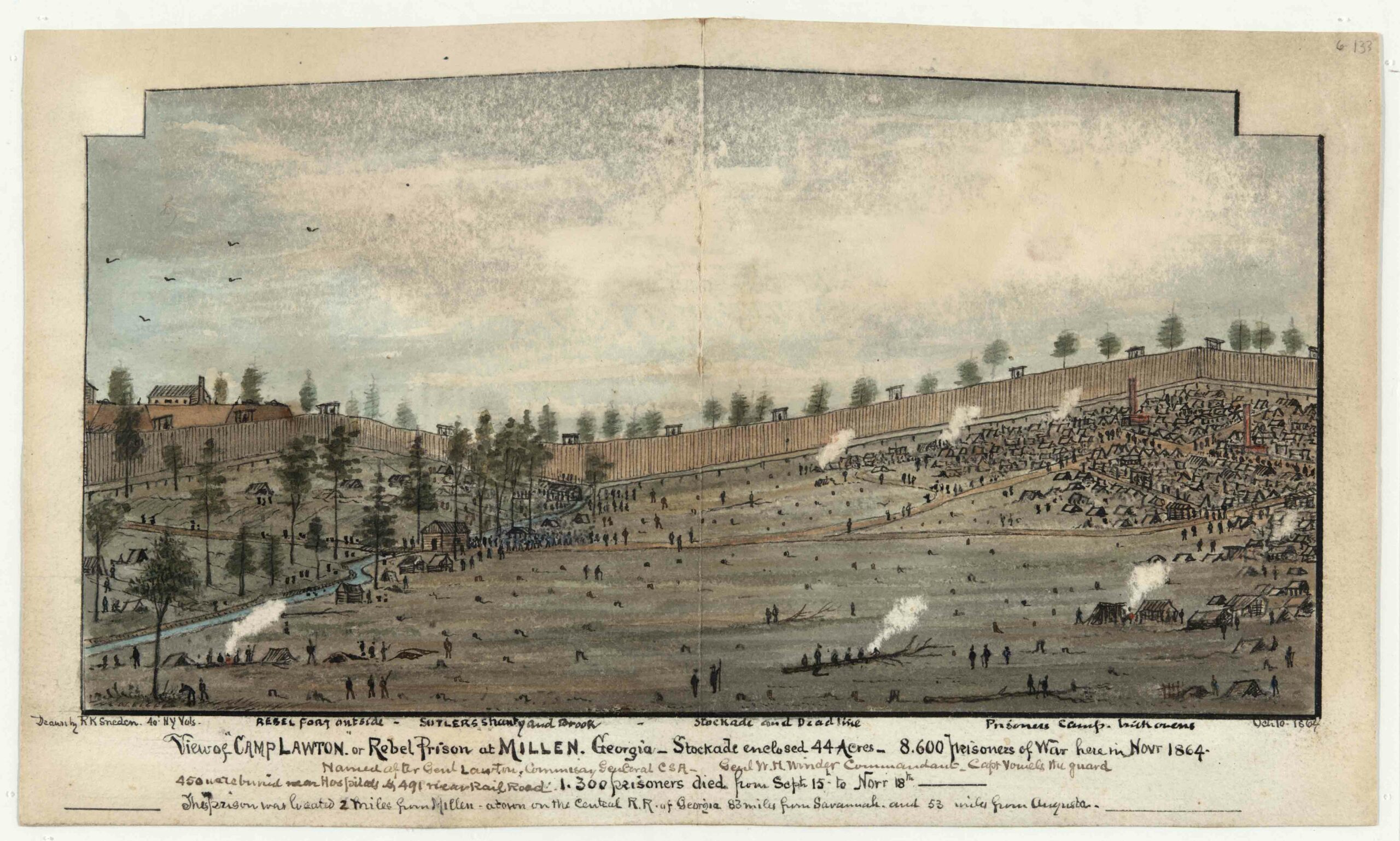

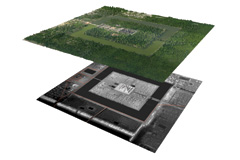

CAMBODIA

CAMBODIA: Every time one looks closely, the scale of Angkor Wat appears to grow larger. Experts have recently turned to airborne laser scanning called lidar, which allows them to see through the dense tree cover that surrounds the site’s monuments. What they found is no less than staggering: that the planned, densely populated “urban core” of the city is some four times larger than previously thought. The finding lends further support to the idea that the city and population grew so large that the local environment could no longer support them. —Samir S. Patel

MADAGASCAR

MADAGASCAR: It was once thought that farmers from East Africa and Indonesia were the first to settle this Indian Ocean island, around A.D. 500. Now, excavation at a rock shelter called Lakaton’i Anja has unearthed fragments of stone tools, bone, and shell in a layer dating to 2000 B.C., suggesting foragers occupied the island much earlier. How these earliest arrivals impacted the island’s distinctive—and now critically endangered—native flora and fauna remains to be determined. —Samir S. Patel

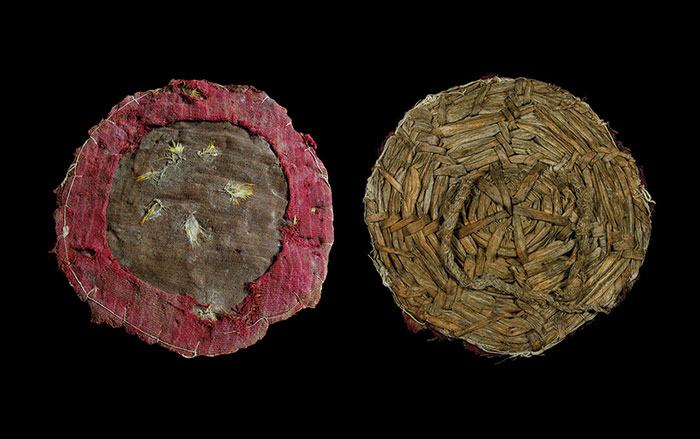

ISRAEL

ISRAEL: Thirteen thousand years ago, the Natufian people in the Levant laid their dead to rest on beds of flowers. In four graves at Raqefet Cave, archaeologists found clear impressions of plants, including sage, mint, and figwort, which suggest spring burials involving colorful, aromatic flowers. The finds represent the earliest known use of a plant lining in graves—flowers for the dead. It is possible that many more Natufian graves had similar floral beds, but preservation of such remains is rare. —Samir S. Patel

BULGARIA

BULGARIA: At a medieval fortress on the Black Sea coast, excavators have found an expertly crafted bronze ring with a curious, cloak-and-dagger adaptation. The head of the ring is hollow with a small hole in the side. A working hypothesis is that it once held poison that could be secreted into a drink. It comes from a period when the fortress, called Kaliakra, was part of a contested principality, and a number of nobles died under mysterious circumstances. Researchers hope residues in the ring will tell a more complete tale. —Samir S. Patel

ENGLAND

ENGLAND: From 1822 to 1854, more than 40,000 bodies—victims of poor hygiene and disease outbreaks—were buried on the grounds of St. Pancras Church in London. During recent high-speed rail work, almost 1,400 sets of remains were exhumed and reburied. In one coffin there were bones from at least eight people, as well as an odd surprise: eight bone fragments from a Pacific walrus. Cut marks suggest that medical students may have been using bones from a 13-foot-long, 3,000-pound pinniped for dissection and surgery practice. —Samir S. Patel

ANTARCTICA

ANTARCTICA: The southern continent hasn’t seen a tree for 30 million years, so one would expect that shipworms, which consume submerged wood in most of the world’s oceans, wouldn’t migrate into these frigid waters. To confirm this and to determine whether historical shipwrecks such as Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance (crushed and sunk by pack ice in 1915) and others survive intact, scientists submerged samples of oak and pine for 14 months. The wood was recovered in pristine condition, though whalebone submerged alongside it was infested with unrelated bone-eating worms. —Samir S. Patel

CHILE

CHILE: As one of the driest places on the planet—rain falls a couple of times per century—the Atacama Desert would have been particularly inhospitable to the hunter-gatherers that migrated into South America some 14,000 years ago. But new excavations at Quebrada Maní (which took four years of searching to find) have turned up stone tools, animal bones, shells, and the remains of a hearth—all in the hyperarid heart of the desert. Scientists studying the site suspect that there were once seasonal oases between which people migrated. —Samir S. Patel

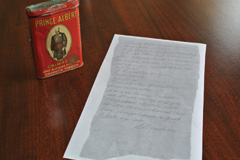

NEW JERSEY

NEW JERSEY: Renovations at Fairleigh Dickinson University have uncovered a message from a time when having a cold one at the end of a day’s work was illegal. In a tobacco tin, seven plumbers and tile workers left a note stating that they had remodeled a bathroom there in 1932. The note reads: “It was during Probition [sic] and it was a very dry Job. The finder of this note if the 18 Amendment has bin [sic] changed have a good Drink on us.” The tradesmen wouldn’t have long to wait—the 21st Amendment put an end to Prohibition the next year. —Samir S. Patel

CUBA

CUBA: A two-year census of archaeological sites in the island nation has revealed some 3,200 ancient aboriginal sites, including 1,000 that were previously unknown. Some may be up to 10,000 years old, according to the official state media. The government project is aimed at creating an atlas of Cuban archaeological sites to aid in their protection and to bring order to the hundred or so cultural groups represented in Cuba’s history. —Samir S. Patel