Jacob Housman may have been the original Florida Man. According to one account—possibly his own—Housman launched his career when he absconded from New York City in the early 1820s with his father’s freight schooner and sailed for the Caribbean, smashing into a reef near Key West. Thus began his initiation into wrecking, a legal and wildly profitable endeavor somewhere between salvage and piracy. Island-based wrecking crews would race to ships that had run aground, relieving them of their cargo and selling it. Housman’s tactics soon made him unwelcome on Key West, and in 1830 he began developing his own town on 11-acre Indian Key. There, he laid out a New England–style street grid with a town square, a bowling alley, workshops for blacksmiths and sailmakers, mansions for the well-to-do, and dwellings for people they enslaved. Indian Key had no source of fresh groundwater, no wood for construction, no soil suited to growing crops, and a single-resource economy that depended on scavenging distressed ships.

By the time archaeologists arrived in 1998 to survey and excavate, the town on Indian Key had been destroyed several times over. Nearly broke, Housman petitioned the U.S. government in 1840 to allow him to bounty hunt Native Americans for $200 a head. That August, a cohort of Native warriors attacked and torched the island, killing 13. During the Labor Day hurricane of 1935, “the whole bottom of the sea blew over” Indian Key, wrote local chronicler Ernest Hemingway. Using historical maps and then-new techniques such as laser scanning, archaeologists revealed the settlement hidden beneath dense overgrowth. “We were in the beating-hot sun trying to map a really large area of mortar-based floors,” says archaeologist Lori Collins of Argonne National Laboratory. “Figuring out the town grid was integral to picking apart the different eras of a very compressed timeline.”

In reconstructing the Indian Key of the 1830s, whose remnants are now protected as part of Indian Key Historic State Park, archaeologists determined that a variety of factors had influenced the town’s plan. The island’s wharves needed to be in deep enough water to dock 30-foot-long wrecking boats, and a warehouse was positioned as near to the wharves as possible, since a wrecker’s haul could be very heavy. The town square separated the noisy, foul-smelling warehouse district from the part of the island where residences and the chic Tropical Hotel were built.

THE SITE

Indian Key is uninhabited today, but its points of interest are well maintained. The rediscovered grid, from First to Fifth Street, is marked with signs. Vegetation has been cleared from the town square, which is likely the location of a courthouse that Housman staffed with his cronies. Just up Second Street lies the warehouse, now reduced to foundations consisting of what archaeologists believe were cisterns sealed with waterproof plaster. Mortar ruins of possible cottages and kitchens dot the island. Housman’s grave, marked by a tombstone but now empty, sits at the corner of Third and Northwest Street. He’s no longer buried there—and perhaps never was. The notorious skipper was crushed between two ships while wrecking in 1841.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

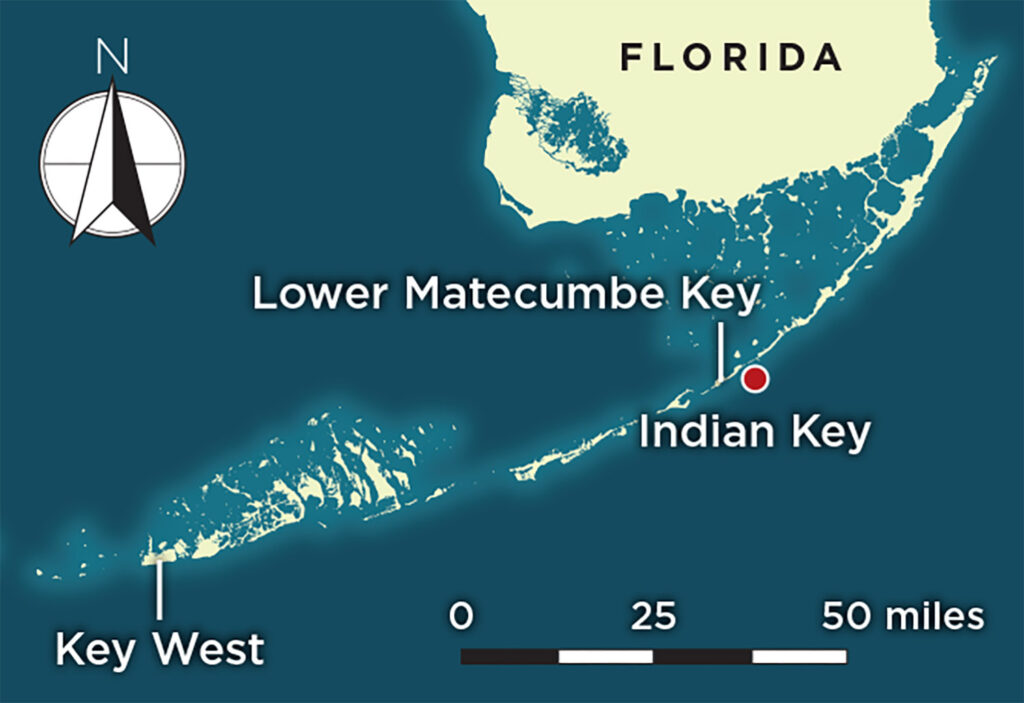

The best way to reach Indian Key is by kayak from Lower Matecumbe Key. There, Robbie’s of Islamorada rents kayaks, and the crossing is an easy half-hour paddle. Picnickers can enjoy shade under absinthe-green tamarind trees brought from Mexico in 1838 by botanist Henry Perrine. Snorkelers might spot mangrove snapper, spiny sea urchins, and even manta rays. Back at Robbie’s, treat yourself to a slice of frozen key lime pie on a stick and pick up a souvenir hand-painted with a Keys proverb such as “A day without a buzz is a day that never wuzz.”