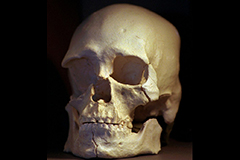

MALAYSIA

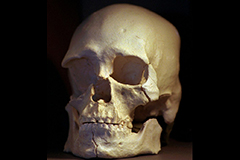

MALAYSIA: The “Deep Skull,” found in 1958, is still the earliest known remnant of a modern human in island Southeast Asia, at 37,000 years old. It had been thought that the skull, from Borneo, came from someone related to indigenous Australians, and that the islands were settled in two waves—first by ancestors to Australians and then by immigrants from Asia who became Borneo’s modern indigenous people. A new analysis, however, found that the skull appears to be more Asian than Australian in origin, suggesting there was just one major migration. —Samir S. Patel

CHINA

CHINA: Broomcorn, millet, barley, Job’s tears, tubers—this ancient Chinese beer recipe probably produced an interesting bouquet. The ingredients were identified from residues found in a variety of clay vessels, including a funnel, that may have comprised a “beer-making toolkit” from a 5,000-year-old site in Shaanxi. The find is also the earliest known identification of barley in the country, suggesting the grain was introduced for beer production rather than as food. —Samir S. Patel

MADAGASCAR

MADAGASCAR: This island nation is 300 miles from the coast of Africa and 3,700 miles from Southeast Asia, but the people there speak Malagasy, an Austronesian language related to Malay and Hawaiian. This suggests that the island was colonized around 1,200 years ago from across the Indian Ocean, but until now there was no physical evidence to back up the linguistic and genetic data. Recently excavated botanical remains have provided the first tangible link—the remains of Asian crops, including rice and cotton—at sites there and on the Comoros islands closer to the African mainland. —Samir S. Patel

MOROCCO

MOROCCO: Early humans certainly competed with large carnivores for resources, including prey and the natural shelter of caves, but there is little direct evidence for their interaction before the Upper Paleolithic (roughly 50,000 to 10,000 years ago), when humans began hunting carnivores in numbers. A hominin bone belonging to the species Homo rhodesiensis and around 500,000 years old, found among a large deposit of bones in a cave in Casablanca, had been cracked, gnawed, and punctured—probably by an extinct hyena. The find shows how easily humans and large carnivores could change places on the food chain. —Samir S. Patel

GEORGIA

GEORGIA: In traditional Georgian banquets today, guests engage in elaborate toasts involving wine drunk from animal-horn vessels. Archaeologists at the site of Aradetis Orgora recently discovered a jar and two animal-shaped clay vessels, one containing pollen from the common grape vine. Belonging to the Kura-Araxes culture and dating to 5,000 years ago (and therefore probably not related to modern traditions), the jar might have been used to decant wine into the vessels for ritual consumption. —Samir S. Patel

LITHUANIA

LITHUANIA: As many as 100,000 people were executed at Ponar, a Nazi killing site, beginning six months before Adolf Eichmann proposed the “Final Solution.” New remote sensing studies of the site have uncovered evidence of several massive burial pits, as well as a 100-foot-long tunnel, dug by spoon and hand, through which a dozen prisoners, who were being forced to exhume burial pits and burn evidence of the killings, managed to escape on the last day of Passover in 1944. Eleven survived the war to provide testimony of the atrocities. —Samir S. Patel

THE NETHERLANDS

THE NETHERLANDS: Outside of caviar, perhaps, only a very few delicacies come in cans. Construction workers at a railway tunnel site stumbled on the remains of just such a treat: a can of turtle soup dating to between 1860 and 1900. The dish has lost popularity in the West for various reasons—the taste, the fact that some are endangered species—but was once coveted enough to grace the tables of European royalty, possibly because turtles aren’t native to northwestern Europe. —Samir S. Patel

PERU

PERU: There are two basic means for an imperial power to impose its will: by replacing the original population or through diffusion of the imperial culture. To examine the rise of the Wari Empire (A.D. 600–1100) in the Andes, geneticists studied DNA from 34 burials at the Huaca Pucllana site dating to before, during, and after Wari rule. The results show only subtle changes in genetic diversity, suggesting that at this site, the Wari did not decimate the people of the Lima culture who already lived there. —Samir S. Patel

ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA

ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA: Life was difficult for the British sailors stationed in the Caribbean during the Napoleonic Wars. Many died from disease, and it is suspected many also fell victim to heavy metal poisoning. Analysis of remains from the cemetery of the Royal Naval Hospital in Antigua revealed lead poisoning—in some cases severe enough to contribute to death. Potential sources of the toxic metal could be linings of water systems, medicines, and, perhaps most notably, rum distilled using lead coils. —Samir S. Patel

WASHINGTON

WASHINGTON: As far as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is concerned, the controversial saga of Kennewick Man is near its end. The 8,000-year-old skeletal remains found in the Columbia River in 1996 have been the subject of legal challenges since it was suggested, based on physical evidence, that they might not be Native American in origin. According to the latest research, the Corps has determined that Kennewick Man is indeed Native American, opening the door for his return to one of the tribes that claims a connection. —Samir S. Patel