As dusk settled over Pompeii, guests strolled into the grand home of one of the city’s wealthiest families for an evening of drinks and delights. Household staff led these privileged Pompeians through a doorway into a portico along the edge of an interior garden surrounded by columns. At the far end, glowing light and the persistent thrum of music beckoned. The partygoers stepped into the vaulted space of a dining room where they were greeted warmly by their hosts. The room’s three walls and the fluted stuccoed columns lining them were painted a rich crimson. Along the tops of the walls, vignettes featured ducks and wild boar hanging by their feet, lifeless thrushes and splayed squid, and fresh oysters and lobsters, offering a preview of the sumptuous feast awaiting those fortunate enough to have secured an invitation.

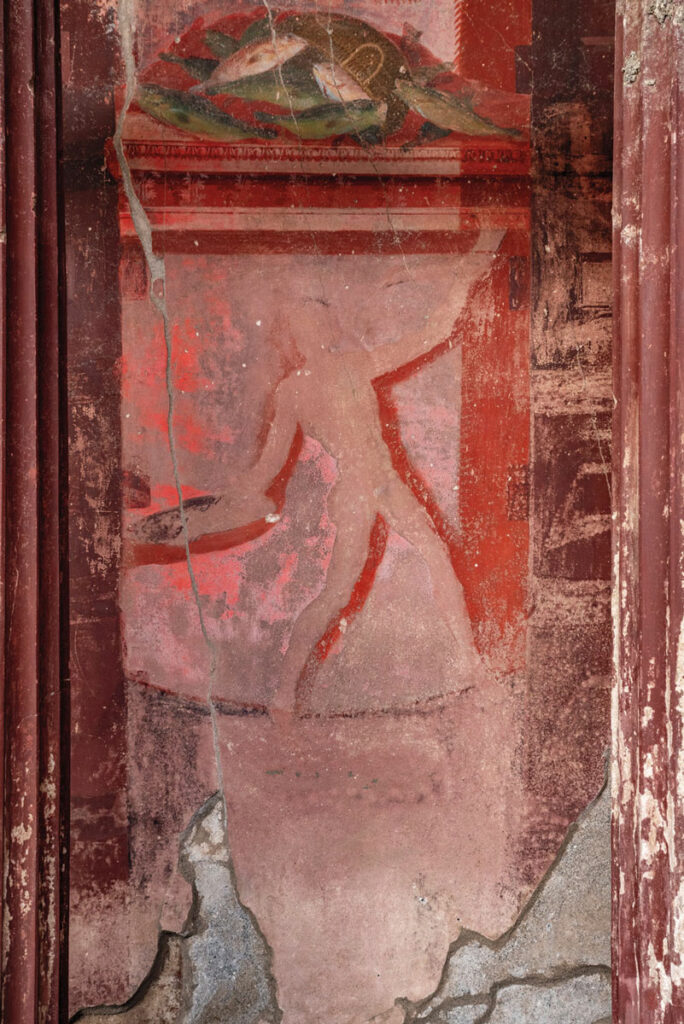

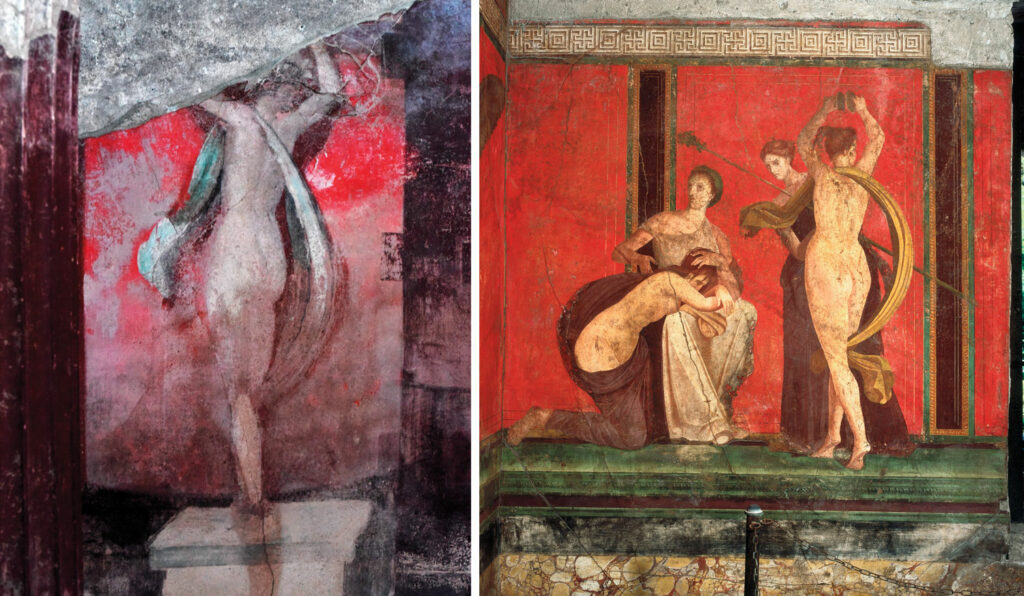

Darkness fell as the banqueters reclined on wooden couches set in front of the columns and began the night’s festivities. Between the columns, frescoes depicting female and male revelers, each positioned on a painted statue base, caught the guests’ attention. One lively satyr played a double flute and another jauntily tossed libations of wine over his shoulder into a shallow bowl. A dancing woman, her hands clashing cymbals above her head, twirled in such ecstasy that her flowing garment exposed her naked body. The guests recognized these figures as participants in a thiasus, a procession of followers of the wine god, Dionysus, whom Romans called Liber or Bacchus. Gazing out at the diners from the center of the back wall was a cloaked woman preparing to be initiated into the god’s mystery cult. She was led by an elderly, torch-bearing silenus, a woodland deity who had educated Dionysus in his youth. For a few of the guests, this scene—and the wine that had already begun to take effect—must have conjured joyful yet hazy memories of their own initiations into the secret rites of Dionysus.

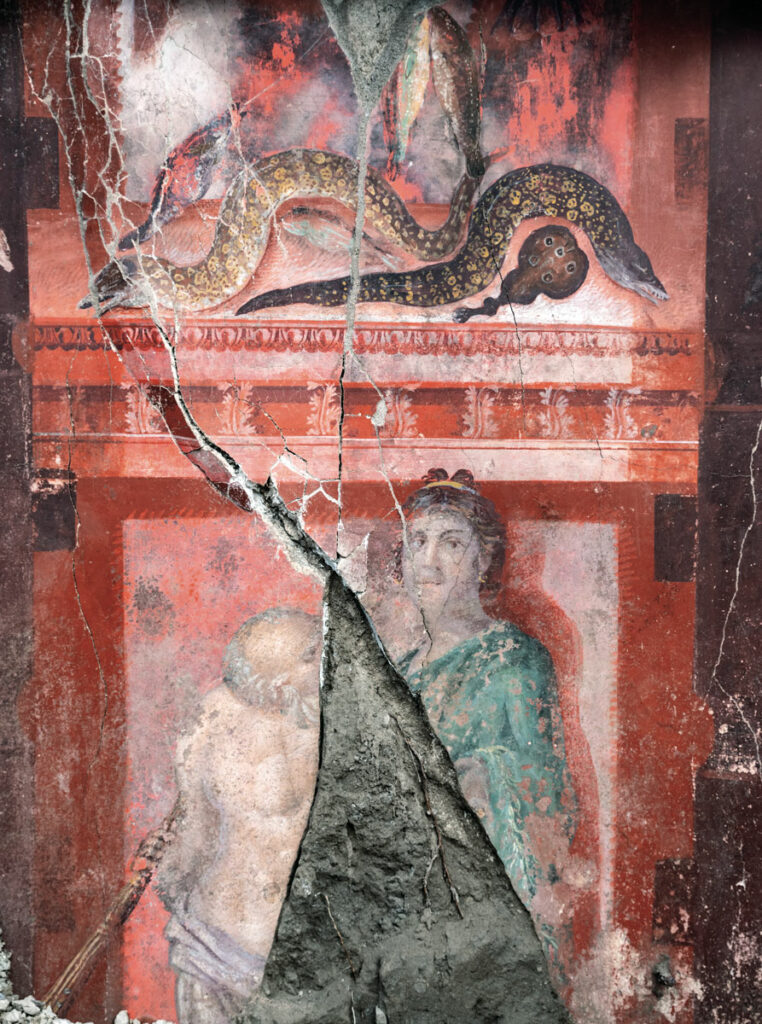

Beneath these scenes of revelry, however, the banqueters saw a hint of something more violent. In one panel, a maenad—a frenzied female follower of Dionysus—with a crazed glint in her eye brandished a sword in one hand and the freshly cut entrails of an animal in the other. A young satyr to her left looked on nervously. These figures stood in stark contrast to those the visitors had seen in the exquisite painting of a Dionysian initiation at a recent party in an opulent seaside villa.

Holding a wine glass in one hand, a diner propped her head against her other hand and peered out toward the garden. She noticed a curious figure in a decorated panel on the wall across from her. There, she saw a woman leaping off her pedestal and running in the direction of the real garden, as if fleeing into the night.

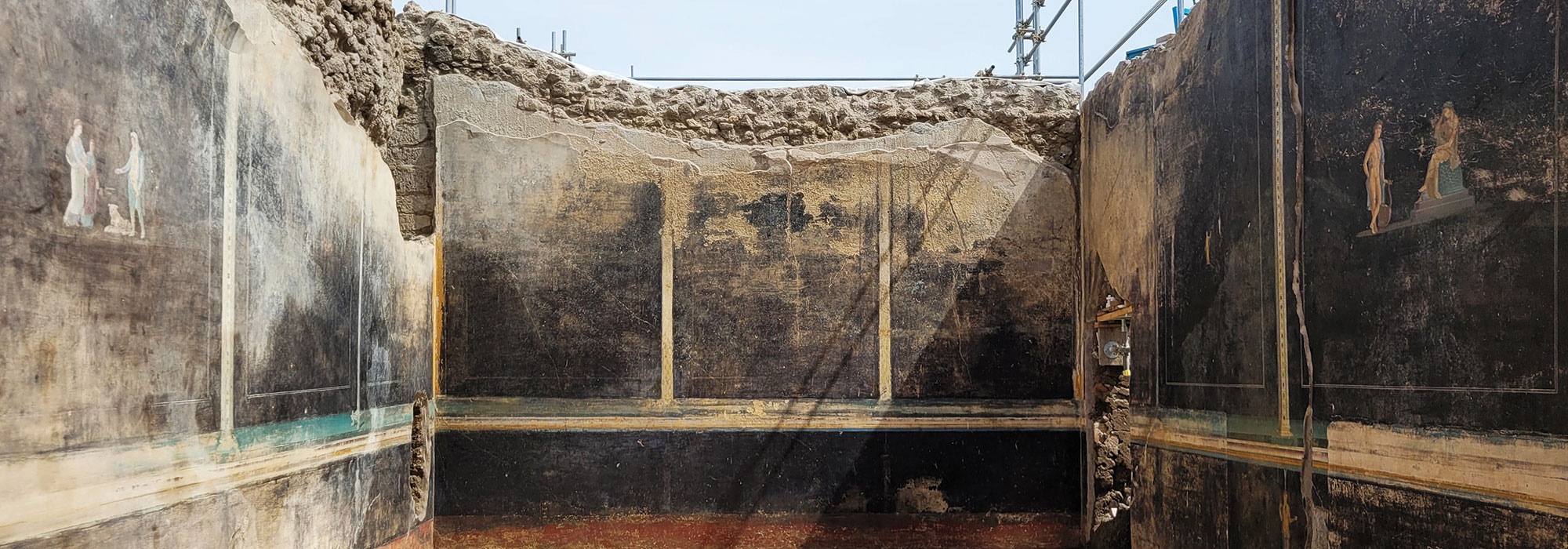

This splendidly decorated residence, a massive property in what archaeologists call Regio IX, once one of Pompeii’s toniest neighborhoods, was surely the site of many such events before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in a.d. 79. That cataclysm buried the celebrants painted on the mansion’s walls in their ecstatic poses forever. In the eighteenth century, excavators tunneled through volcanic debris into the house in search of marble statues and other precious artifacts, hacking through the walls and destroying at least one of the dining room’s 17 frescoed panels. The house remained otherwise unexplored for centuries, until a team from the Archaeological Park of Pompeii undertook excavations starting in 2023 to stabilize and restore the city block where the house is located. Archaeologists began to unearth vibrant wall paintings in what they soon discovered was an approximately 1,000-square-foot columned reception hall, where the home’s owners entertained their guests. The frescoes’ subject matter inspired scholars to name the residence the House of the Thiasus, much like excavators more than a century ago had dubbed an opulent residence in another part of Pompeii after its enigmatic Dionysian depictions.

Dated to between 40 and 30 b.c., the frescoes in the House of the Thiasus form a megalography—a cycle of paintings featuring nearly life-size figures. (See “Top 10 Discoveries of 2025: Dining with Dionysus.”) The only other example of a large-scale painting in Pompeii with similar subject matter was discovered in 1909. During excavations of the residential area of a sprawling agricultural estate overlooking the sea just outside one of the city’s main gates, archaeologists uncovered an intimate room with walls painted an even deeper red than those in the House of the Thiasus. This room contained a stunning narrative painted perhaps 20 or 30 years earlier than the frescoes in the House of the Thiasus that is also thought to depict a woman’s initiation into the secret rites of Dionysus. This house came to be known as the Villa of the Mysteries. (See “Saving the Villa of the Mysteries.”)

With the discovery of the paintings in the House of the Thiasus, scholars are beginning to reconsider what they once thought was unique to the Villa of the Mysteries. The two Dionysian megalographies share nearly identical figures with which viewers would have been intimately familiar from other representations, says archaeologist Molly Swetnam-Burland of William & Mary. But Pompeian artists rendered them in surprisingly different ways, likely intending to evoke distinct emotions and, for some viewers, memories of participating in the Dionysian cult themselves. “While the Villa of the Mysteries was absolutely a unique composition designed to fit that specific space, it’s now apparent that this imagery was in much wider currency,” Swetnam-Burland says. “The paintings in the House of the Thiasus are adding new elements and more depth to what we know about Dionysus’ ritualistic images in Pompeii.”

For more than 2,000 years, Dionysus was revered throughout the Greco-Roman world, but the precise nature of how people worshipped the god remains elusive. Few temples were devoted to Dionysus, though statues of him stood in sanctuaries primarily dedicated to other gods. Nevertheless, scores of inscribed dedications to the god and carved masks portraying him were prominently displayed inside theaters, one of Dionysus’ primary domains as patron of the dramatic arts.

These public displays of veneration, however, were merely one way people demonstrated their devotion to Dionysus. Many chose to worship him in a more private capacity. Archaeologists have found texts inscribed on gold tablets in graves throughout Greece and southern Italy that contain references to “the Bacchic one” releasing his followers into the afterlife. These texts suggest that worshippers began to participate in the mystery cult of Dionysus as early as the fifth century b.c. While membership in these private cult organizations differed from city to city, says historian Stéphanie Wyler of Paris City University, most seem to have included both women and men. The head of each association was usually a woman, who acted as mater, or “mother,” of the thiasus. Female and male initiates were known as bacchae and bacchoi, terms derived from the name Bacchus.

Little is known about the cult’s nocturnal rituals, beyond the fact that they were said to take place in the wilderness outside city walls and to involve dancing and drinking wine. “Because they were mysteries, participants weren’t supposed to divulge what occurred during the rites,” Wyler says. “Most of the evidence we do have about the cult is textual, speaking about the mysteries from a pejorative point of view.” For example, in the Bacchae, a tragedy by the fifth-century b.c. Greek playwright Euripides, maenads murder the mythic Theban king Pentheus, tearing his body limb from limb after he bans the worship of Dionysus.

By the third century b.c., the Dionysian mysteries had spread to the Italian peninsula, where followers founded private associations similar to those that had existed for centuries in Greece. Devotees’ raucous rites caused a scandal in 186 b.c., when the Roman Senate issued a decree prohibiting people from participating in rituals broadly referred to as bacchanalia. In his hyperbolic account of this affair, the first-century b.c. Roman historian Livy claims that Dionysian initiation rites involved promiscuous liaisons among women and men, as well as same-sex pairings. He also charges that the cult bred all manner of corruption, including forgery, false testimony—and even murder. “Livy’s treatment is especially telling,” says Swetnam-Burland, “because he extends women’s transgressive behavior to actions that would undermine the Roman political establishment and male elite power. This expresses deep-seated anxieties about the power of the female body.” Neither this moral hysteria nor the decree, however, suppressed Dionysus’ mystery cult, which was especially popular among women and men from wealthy and important families. “The cult quickly became very fashionable and remained so during the empire,” says Wyler. “It was pretty common, and not problematic at all, to be part of an association that practiced the mysteries of Dionysus.”

Pompeii’s residents seem to have had a particular affinity for Dionysian worship from early in the city’s history. In the mid-third century b.c., Samnites, Pompeii’s Oscan-speaking founders, built a public temple outside the city. This temple was dedicated to Loufir, the Oscan name for the deity that Pompeians would later come to conflate with Dionysus. Loufir bears a close linguistic, and likely ritual, connection to Liber, “the free one,” one of the god’s Latin names. Perched atop a hill overlooking the Sarno River, the small temple would have been visible to travelers along the waterway and a main north-south road. After Pompeii became a Roman colony in 80 b.c., worshippers continued to use the temple, maintaining and upgrading it even as the city approached its untimely end. In the early first century a.d., two dining rooms were installed in front of the building, with built-in couches that archaeologists estimate could have accommodated 20 banqueters. In 1973, archaeologists made plaster casts of ancient vine roots identified at the site. The casts revealed that entwining grapevines climbed trellises arching over these dining spaces. Wyler says private groups may have rented the temple to practice their particular version of the mysteries more than 300 years after its construction. “There was a consistent, prolonged appreciation of this cult in Pompeii,” Swetnam-Burland says, “and Dionysian iconography was viewed positively throughout that time.”

Sculptures on the temple’s pediment show Dionysus reclining at a banquet, holding a large bunch of grapes in one hand and a drinking cup in the other. Wyler suggests that Dionysus’ role as a fertility god made him especially appealing to citizens of Pompeii, where viniculture was a pillar of the economy. High-quality wine from the region—much of it produced on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius and in fields surrounding Pompeii—was exported throughout Italy. “That might be one reason for Dionysus’ success in the city,” says Wyler. “If you were a rich owner of vineyards or a wine exporter, it would make sense that your favorite god is Dionysus.” A large area of the farm around the Villa of the Mysteries was dedicated to wine production, a pursuit echoed in the Dionysian decor of the dining room. “Even though the artwork could explore themes like wildness and dangerous bodies,” says Swetnam-Burland, “it wasn’t imagery that homeowners hid away.”

The frescoes adorning the dining room walls of the Villa of the Mysteries and the House of the Thiasus express variations on the narrative of initiation into the mystery cult of Dionysus, and their artists may have intended to elicit different reactions from viewers. Dionysus appears at the center of the frescoes in the Villa of the Mysteries. Reclining in the lap of a woman, head lolling to the side and mouth agape, he looks as if he has drunk too much wine during his revels. In the House of the Thiasus, however, the god is not depicted at all. To viewers in this room, Wyler says, images of satyrs and maenads who are part of Dionysus’ retinue would have served as a visual shorthand for the deity’s cult rituals. “If a thiasus is depicted, Dionysus is very close, even if he’s not painted in the scene,” she says. “While drinking wine, banqueters would have experienced an altered state of consciousness, and probably would have thought that the god was there.”

The artists who painted the scenes in both dining rooms portrayed mythic and human figures in strikingly similar ways. For example, a naked dancing maenad with a billowing garment appears in both residences. In each case, the maenad is depicted with her back turned and arms thrown overhead, her dance causing her clothing to flare away from her body. Comparable depictions of maenads appear in almost the same posture in many Roman sculptures. They were also popular subjects on marble sarcophagi dating to the second century a.d. and later, more than 100 years after the frescoes in Pompeii were painted. “This maenad was clearly a stock type,” Swetnam-Burland says. “Roman audiences could see it and immediately understand that she’s in ecstasy and celebrating the god. The fact that we see this type in painting and sculpture means that it was recognizable and that artists had some kind of template they were using to produce the image.” Since the paintings in the dining rooms were created just decades apart, Swetnam-Burland thinks the presence of these stock types might suggest that artists from a single workshop were responsible for both compositions.

The Villa of the Mysteries’ frescoes depict a complete narrative of a woman’s initiation that viewers could follow across the dining room’s walls. Portrayals of the initiate are interspersed with images of other women doing everyday activities. The initiate is shown being flogged as part of the rituals, an experience believed to represent personal growth through an encounter with the divine. In contrast, the woman at the center of the House of the Thiasus scene appears to have just begun her initiation, a hint of trepidation on her face as she’s led away. Surrounding her are maenads draped in animal skins and clutching the beasts’ entrails, an example of women engaging in the sort of wild behavior that distinguishes these paintings from those in the Villa of the Mysteries. Where animals appear in the villa, they are shown being tended to and protected, unlike in the House of the Thiasus, where they exist to be hunted. “It’s a peculiar expression of what we have in Euripides’ Bacchae,” says Wyler. “They’re killing animals and eating raw meat. The idea isn’t new, but I’ve never seen this represented in that way in Dionysian paintings.”

The vignettes above each frescoed panel in the House of the Thiasus add to the undercurrent of violence and wildness. These paintings depict an abundance of food in the form of living and dead animals, including fowl, shellfish, and other types of seafood, the kinds of culinary delicacies that guests might enjoy at a banquet. They also recall the feral maenads handling dead animals with their bare hands. “All the meat shows evident butchery, with gaping seams in the sides of animals where the entrails have been removed,” says Swetnam-Burland. Absent from the paintings are fruits and vegetables, as well as the elegant cloth napkins and silver plates that Pompeian artists commonly included in still lifes featuring food. “This suggests that these scenes, while they probably promised a lavish feast, were intended to enhance the viewer’s awareness of the wild, dangerous abandon of the people depicted below, who have lost themselves and some degree of their humanity to the veneration of Dionysus,” she says.

Like the rooms’ decorations, their layouts would have influenced the way a viewer experienced the scenes. In the Villa of the Mysteries, diners would have reclined on couches positioned right next to the walls, placing them at eye level with the events. “Artists created this vivid, interactive, highly personal scene that’s almost a kind of virtual reality,” says Swetnam-Burland. “The viewer is thinking about the figures looking at each other through real space, and feels as if they’re witness to the action.” In the House of the Thiasus, by contrast, the columns lining the room’s three sides literally separated the viewer from the figures painted on the wall. These real columns aligned with painted columns that divided the panels and separated the figures from one another. “This arrangement enhanced the distinction between the world of the diner, feasting on delicious food, and the world of the retinue, which is treated as art,” Swetnam-Burland says. “The figures are placed on statue bases and are therefore a little bit more removed from the viewer’s personal experience.”

Since the Villa of the Mysteries was unearthed more than a century ago, scholars have proposed varying interpretations of what its frescoes may reveal about the covert rites of Dionysus’ cult and what the paintings meant to viewers. The discovery of the House of the Thiasus offers another means of investigating the experience of ancient diners in these rooms. To Swetnam-Burland, the imagery in both houses expresses a sense of freedom and release that guests would likely have felt profoundly as they shared in a banquet’s conviviality. “I think that it may have been a reminder that everyone has the ability to transcend expected behavior and social roles,” she says. “The more you indulge in the gifts of Dionysus, including grapes and wine, the more likely you are to let loose and find a version of yourself that is less controlled. Inspired by the god, there are times and places where you could become something else, something wild and powerful.”

Uncover More of Pompeii’s Past

While digging a water tunnel in the late sixteenth century, architect Domenico Fontana stumbled upon the ruins of Pompeii, whose location had been forgotten in the 1,500 years since its destruction. Systematic excavations began at the site in 1748 and have continued throughout the ensuing centuries. Read more about the many exciting discoveries made during the past decade of research at Pompeii—including investigations of previously unexcavated areas of the city—by clicking the links below.

The Archaeology of Gardens: Food and Wine Gardens

Digging Deeper into Pompeii’s Past

A Ride Through the Countryside

Letter from Vesuvius: Digging on the Dark Side of the Volcano