Latest News

-

News December 15, 2025

4,400-Year-Old Sun Temple Excavated in Egypt at Old Kingdom Necropolis

Read Article Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities -

Auckland Museum

Auckland Museum -

Photo by Boel Bengtsson/Fauvelle et al., 2025, PLOS One

Photo by Boel Bengtsson/Fauvelle et al., 2025, PLOS One -

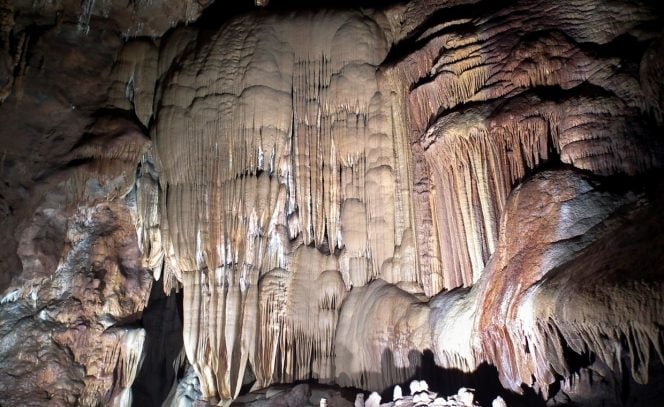

Garry K. Smith, Newcastle & Hunter Valley Speleological Society

Garry K. Smith, Newcastle & Hunter Valley Speleological Society

-

News December 15, 2025

New York’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit Recovers and Returns Looted Artifacts to Turkey

Read Article

-

-

Craig Williams, Illustrator, Department of Europe and Prehistory

Craig Williams, Illustrator, Department of Europe and Prehistory -

Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Archaeological Park of Pompeii

-

INAH

INAH -

© Anthony Robin, INRAP

© Anthony Robin, INRAP -

-

-

Julia King

Julia King -

Christoph Gerigk ©Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

Christoph Gerigk ©Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation -

News December 8, 2025

Earliest Evidence for Lost-Wax Casting Technique in Western Europe

Read Article Photo by B. Meunier (MRAH)

Photo by B. Meunier (MRAH) -

News December 8, 2025

DNA Study Offers Insight into the Builders of One of Neolithic China's Most Influential Cities

Read Article IVPP

IVPP -

News December 8, 2025

Roman Britain Mosaic Features Scenes Based on Lost Trojan War Tale

Read Article © ULAS

© ULAS -

News December 5, 2025

Sacrificial Complex in the Southern Urals Reveals Nomadic Rituals

Read Article Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences -

News December 5, 2025

Dig Uncovers 6,000 Years of History Beneath Palace of Westminster

Read Article © R&R Delivery Authority

© R&R Delivery Authority -

Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports

Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports

Loading...