Latest News

-

News February 13, 2026

DNA Study Reveals Survival and Persistence of Low Countries Hunter-Gatherers

Read Article Provincial Depot for Archaeology Noord-Holland

Provincial Depot for Archaeology Noord-Holland -

Vitale Stefano Sparacello

Vitale Stefano Sparacello -

Jo Osborn

Jo Osborn -

© City of Cologne/Roman-Germanic Museum, Michael Wiehen

© City of Cologne/Roman-Germanic Museum, Michael Wiehen

-

-

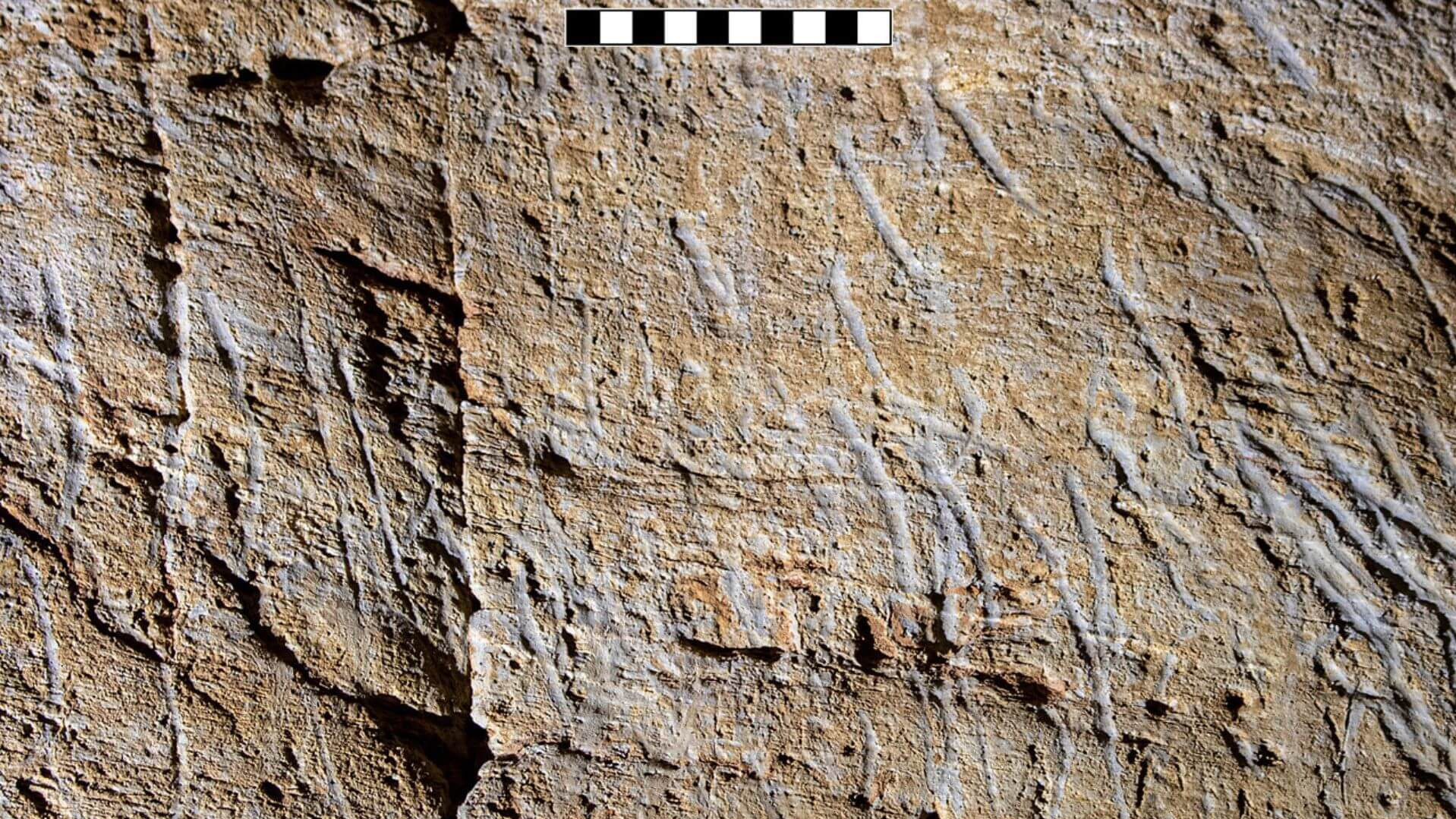

Walls, et al

Walls, et al

-

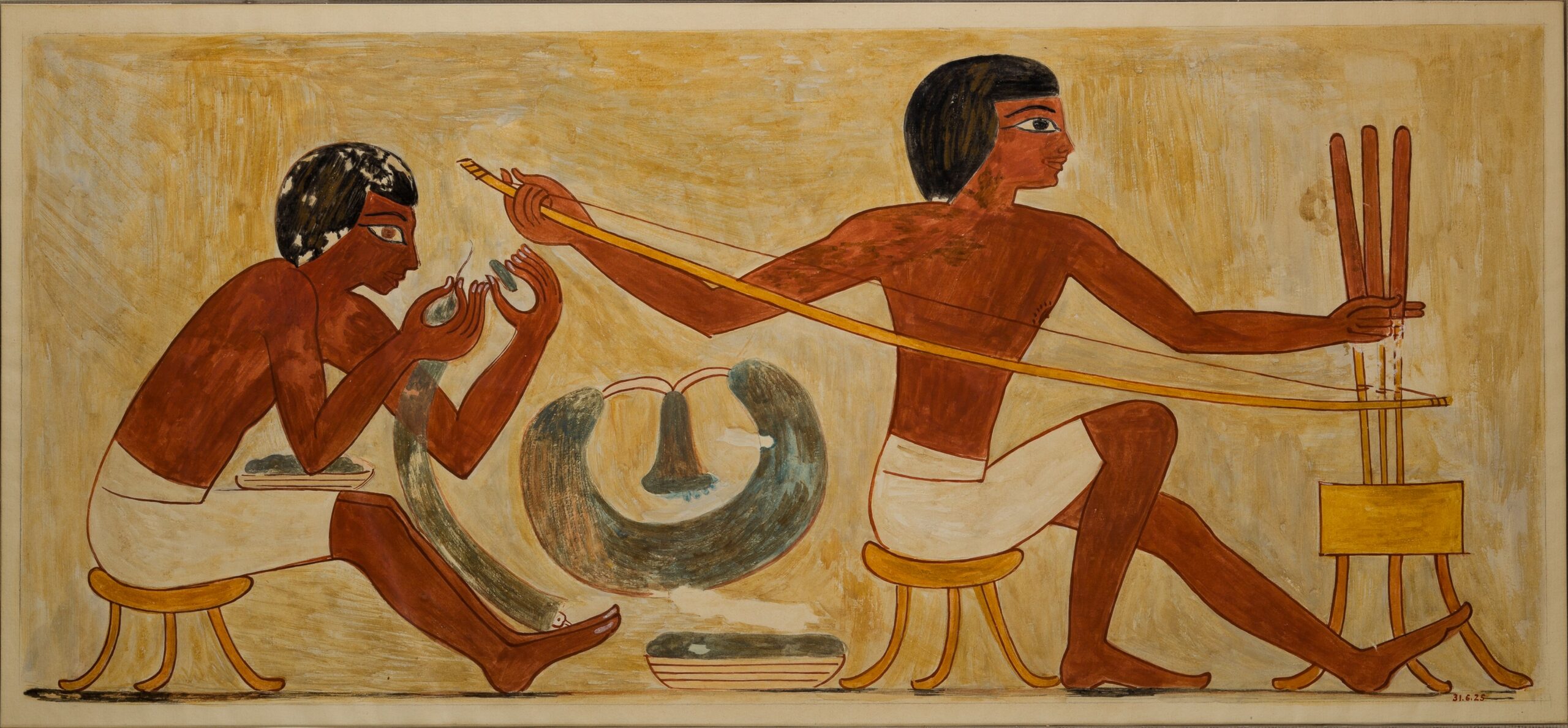

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art -

© Archäoteam, Regensburg

© Archäoteam, Regensburg

-

News February 11, 2026

What Caused Ancient People to Abandon a Fruitful Bison Hunting Site?

Read Article Yellowstone National Park via flickr

Yellowstone National Park via flickr -

© State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták

© State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták -

News February 10, 2026

New Research Confirms Location of Lost City Founded by Alexander the Great

Read Article © Charax Spasinou Project/Robert Killick, 2022

© Charax Spasinou Project/Robert Killick, 2022 -

Prof Alice Roberts/BBC/ Rare TV

Prof Alice Roberts/BBC/ Rare TV -

News February 9, 2026

Excessive Rainfall Might Have Doomed Ancient Chinese Civilization

Read Article

-

Italian Ministry of Culture

Italian Ministry of Culture -

News February 9, 2026

Iron Age Village and Early Medieval Cemetery Unearthed in Scotland

Read Article Scottish Water/Steven Birch and Andy Hickie

Scottish Water/Steven Birch and Andy Hickie -

Courtesy Richard Rosencrance

Courtesy Richard Rosencrance -

Italian Ministry of Culture

Italian Ministry of Culture -

News February 6, 2026

Mysterious Medieval Tunnel Discovered Under Neolithic Monument in Germany

Read Article © State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Simon Meier

© State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Simon Meier -

Cambridge Archaeological Unit/David Matzliach

Cambridge Archaeological Unit/David Matzliach -

Loading...